I. Hyper

Is it just me, or is it hot in here? It’s warm, right?? Are YOU warm???

That was me in almost every room that summer. I was constantly clammy and flushed.

Of course I was self-conscious about my sweat-soaked shirts, which created a vicious cycle where I would be hot and sweaty at baseline, then I’d get anxious about the sweating, and then start overreacting to THAT anxiety.

My heart would be racing while sitting idle in a chair or lying in bed.

People told me I was talking too fast, and my usual temperament was crankier than usual (and it’s pretty cranky on a regular day, TBH). I got into some spats with the co-workers in the lab that landed me in hot water with my boss.

Then I started having panic attacks. I would suddenly start hyperventilating and feeling like I wasn’t getting enough air.

I’d stare at the ceiling for hours, unable to sleep.

At first, I chalked all of this up to the stress of residency, too much caffeine, not enough sleep, eating too much southern BBQ (the “meat sweats” are real, y’all).

What finally got me worried was when I started dropping weight. I have always been a little overweight, but I began losing inches off my waistline without any effort.

Five pounds, then ten, fifteen, twenty. My mentor joked that my jeans were sagging and I needed to buy a smaller belt.

Finally, in December I went to the doctor. After some resistance, I gave in and listened to my wife—who is smarter than me about a lot of things—and scheduled an appointment at the student health center. My hesitation was because I was terrified that it was all psychosomatic, that I was basically going crazy, and all of my results would be normal.

Well, that turned out to be a short-lived concern.

On physical exam, the doctor felt my neck and it was notably swollen, which I hadn’t noticed. They had a pretty good idea what was wrong with me based on the history and exam, but they ordered panels of labwork to confirm. My thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) was essentially undetectable, indicating it was severely suppressed. My total and free thyroid hormone (fT4) levels were more than twice the upper limit of the normal range. I was massively hyperthyroid.

Being the lab nerd that I am, I texted my test results to a few fellow clinical pathology residents. One of them wrote back “You’re a hyperthyroid cat!”

Like cats with hyperthyroidism, I had all of the classic signs:

Anxiety

Goiter

Heat intolerance

Increased heart rate and blood pressure

Irritability

Sleep difficulties

Weight loss

Besides these, there were weirder symptoms that I’m still not sure if they were linked to my thyroid, coincidentally concurrent, or in my head. My eyes would randomly water, sometimes just one eye but not the other. Fine muscles would twitch or spasm—sometimes an eyelid, sometimes in my arms and legs.

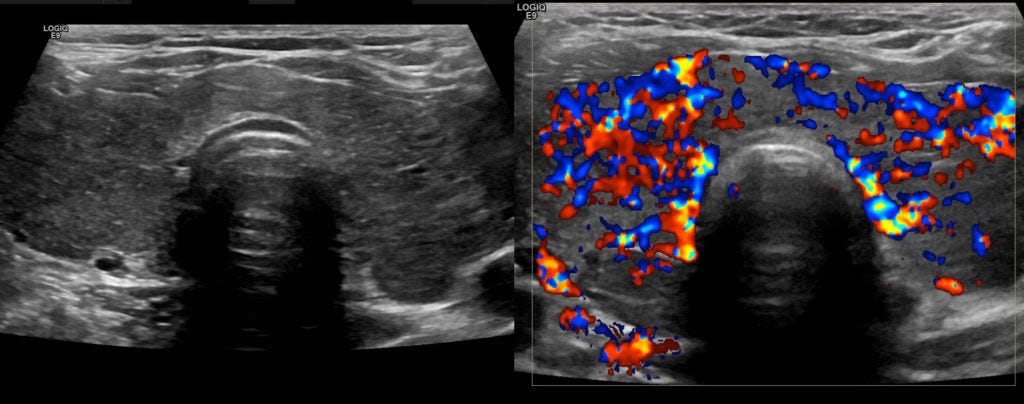

Unlike cats with functional nodules or adenomas, different diseases tend to cause hyperthyroidism in people. To find out more, I was sent to a radiology center for an ultrasound of my neck, which showed diffuse, homogeneous enlargement of my thyroid gland with increased blood flow:

Everything about my case, including the bloodwork and ultrasound findings, was classic for Grave’s Disease (GD), an autoimmune disease that represents the most common cause of hyperthyroidism. The GP referred me to a local endocrinologist who started me on several drugs: methimazole, to block production of thyroid hormones, and metoprolol, a beta-blocker to prevent cardiac complications.

Over the next several months, I slowly began to feel better, but this was just the beginning…

II. Affection of the Thyroid Gland

Grave’s Disease is named after the Irish physician Dr. Robert Graves who reported three cases of women with the triad of heart palpitations, goiter, and exophthalmos in 1835. As with many medical eponyms, there is some controversy over who truly first described the condition of hyperthyroidism, as several other doctors reported the condition around the same time, and the Persian physician Sayyid Ismail Al-Jurjani noted similar symptoms around 1100 AD.

What is Grave’s Disease actually doing inside the body? The basic pathophysiology goes like this: For one reason or another, the body begins producing antibodies that bind to the TSH receptor, causing it to overproduce a ton of thyroid hormone. Virtually every organ of the body is impacted by T3 and T4. They raise the set-point for the body’s thermostat in the brain and crank up your metabolism. They increase production of receptors in the heart and blood vessel that increase how hard and fast cardiac cells beat and make blood vessels tense up.

Grave’s Disease can even impact tissues like the eyes. One of the most prominent features Dr. Grave noted was exophthalmos, or eyes bugging out of the head (as in the image at the top of this article). This complication of autoimmune hyperthyroidism has been reported to occur in up to half of patients, though more recent studies have shown the prevalence is probably lower and decreasing, with most modern GD patients having no eye involvement. Fortunately, this was the case for me (the condition can be disfiguring and require plastic surgery). The specific mechanisms are uncertain, but elevated thyroid hormone levels seem to cause accumulation of mucinous substances and edema fluid around the eyes and limbs of some patients. Smoking and difficulty achieving remission are two of the biggest risk factors.

Left untreated, hyperthyroidism can be fatal. Chronic severe elevations in T3 and T4 can result in a thyroid storm which leads to heart failure. Luckily, this is rare, and in most developed countries the disease is caught and managed long, long before that point is reached.

III. Low

I had been treated medically for over at year at the local endocrinologist, and my T4 and T3 were now normalized. My TSH got into the normal range six months into treatment, but then dipped back down and stayed stubbornly low. I still felt like crap and was plagued by anxiety and a racing pulse. That doctor assured me this was normal, that it just took time to recover, and that my labs every recheck “looked great.”

About 18 months after my initial diagnosis, I started asking questions. One of my college friends is an internist in Manhattan and I texted her my labwork. She said it did not look like I was well-controlled and recommended I seek a formal second opinion elsewhere.

I was tired of getting blown off my my local endocrinologist, and there weren’t a lot of options near me in east Alabama, so I scheduled an appointment with the Kirkland Clinic at the UAB Medical School in Birmingham, AL more than 2 hours away. At my initial appointment an endocrinology fellow and the attending faculty member poured over my medical records and test results. I told them I hadn’t been feeling great and asked if I might have relapsed.

The attending physician paused to think of how to tactfully phrase their response. “From what I can tell,” he said, “you were never actually even in remission.”

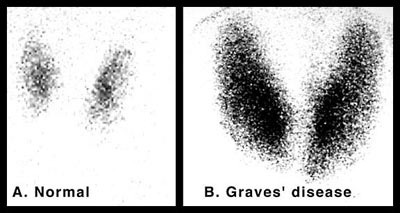

They recommended re-running a battery of tests to make sure the original diagnosis was correct before discussing treatment options. They ran a test for Thyroid Stimulating Immunoglobulin (TSI)—the autoantibodies that stimulate the TSH receptor—which was off the charts. They ran a nuclear technetium-99 scan of my neck that showed a uniformly enlarged gland on both sides of my neck with massive increase in dye uptake:

Everything was consistent with Grave’s Disease. The diagnosis was right, but the treatment had been mismanaged. They recommended destroying my thyroid with radioactive iodine (RAI), which has become the standard of care in most endocrinology clinics. Afterwards, I would require lifelong supplementation with synthetic thyroid hormone.

On a cold January morning in 2018, I drove up to UAB for my RAI. A bunch of staff wearing gloves and lead protective gear brought out a metal box with the nuclear hazard symbol that looked like it could contain a bomb and carefully withdrew the treatment inside with forceps. It just looked like a boring white oblong pill without any hint that it was bursting with radioactivity. I swallowed it with some water and then they told me to mask up so I wouldn’t breathe isotopes on anyone. They gave me a list of detailed instructions on quarantining from other people and animals in my house.

For the first couple days I took off work and slept in my home office. Later that week I stopped by the vet school to get some things and had one of the oncology staff run a Geiger counter on me to see if I was still radioactive. Watch a video of that part (make sure to listen with sound on):

Yes, I was still glowing.

Over the next several months I felt a little better, and then a LOT worse. Hypothyroidism is the expected outcome of RAI, but it hit me like a mack truck. You can see in the chart below that my TSH peaked at an eye-popping 37 (normal is ~0.3-5) before the levothyroxine started to kick-in.

The best way I can describe the feeling of severe hypothyroidism is being tired on a CELLULAR level, like running on an almost dead battery 24/7. Everything moves in slow motion, especially thought. I normally run hot (even before GD), but now I was cold all the time. I gained weight despite diet and exercise. When I went to the gym I had to excuse myself to avoid passing out because my heart rate was too low to keep up with my body’s needs during exercise.

Little by little, I improved. It took most of that year to get my levels stabilized and feeling better. Towards the middle of the following year, my TSH crept up again, and I started to feel that old familiar sluggishness creep in.

This is how things went. Going in to get blood drawn several times a year. Levels drifting up and down, tweaking medication levels.

My new normal.

IV. Why Did this Happen?

We still don’t know exactly what triggers autoimmune disease, including Grave’s hyperthyroidism or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. The conventional wisdom is it some combination of genetic predisposition and environmental triggers in a susceptible individual. Autoimmune thyroid disease is overwhelmingly more common in women than men for reasons that remain unclear. Autoimmunity also tends to beget more autoimmunity; people with Grave’s or Hashimoto’s are more likely to have other immune-mediated conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, type I diabetes, and celiac disease.

Studies in twins suggest that almost 4 in 5 cases of thyroid disease can explained by heredity. Supporting that genetic link, at least two members of my family have been diagnosed with Hashimoto’s hypothyroidism, one years before me, and one after. Variations in the HLA genes that govern transplant rejection may play a role in autoimmunity. Others include mutations in genes for thyroglobulin, the TSH receptor, and white blood cell receptors. The DNA sequencing company 23andMe does not directly test for any of the genes that have been implicated in Grave’s disease, although I do have HLA gene variants that are associated with developing celiac.

Environmental factors also likely play a role. I grew up in a suburb of Western New York between Buffalo and Niagara Falls. In the first half of the 20th century this part of the Rust Belt was home to numerous industrial car and chemical plants, and pollution of local rivers and waterways (including the notorious Superfund site Love Canal) was a serious problem. Epidemiology studies have shown significantly increased rates of autoimmune thyroid disease in WNY (although interestingly only a higher rate in women, not men).

Then there are the numerous occupational hazards I was exposed to over the years in school and work. I periodically held animals for x-rays and was in the room for other radiology procedures like fluoroscopy (I always wore appropriate lead shielding and dosimetry badges). My work in various undergraduate and graduate research labs involved a number of potentially dangerous chemicals ranging from phenol to xylene. Any one of these exposures, or a combination, could have increased my risk.

Finally, many patients develop autoimmune diseases, especially thyroid, during periods of stress. The mechanisms are unclear, although elevated levels of cortisol and other hormones can have profound impacts on the immune system. Of myself and my two close guy friends who developed autoimmune thyroid conditions, all were during graduate or veterinary school.

Whatever the ultimate cause was, we will probably never know for sure.

V. 80-percenter

I have now been living without a thyroid gland for the past five years. Most of the time I forget about that chapter in my life, except the few minutes every morning when I have to remember to take my levothyroxine and wait 30-60 painful minutes without coffee or breakfast (thyroid medication must be taken on an empty stomach because food decreases absorption).

I’m generally well-controlled, although I don’t feel like I did a decade ago before I got sick. I often wake up tired even after a full night’s sleep, but I can function. There’s intermittent brain fog. My mood fluctuates when the pharmacy switches my medication brand. Some of this could definitely be dealing with life (did anything major happen to the world in the last few years? I can’t remember) or simply aging—it’s been nearly a decade since I first started showing symptoms.

In 2013, Meghan O’Rourke published a moving account of her struggles with autoimmune thyroid disease in the New Yorker (“What’s Wrong with Me?”). One passage describing a recheck with one of her better doctors captures the experience well:

I made my way to my doctor’s busy office, and sat with people who looked very, very sick. When I raised concerns about how I was doing, my doctor told me, “This may just be how it’s going to be. You may always feel like you’re eighty per cent.” She intended, I think, to help me adjust to a new reality, but the effect was the opposite.”

I can relate to the sentiment about being an “80-percenter.” In the grand scheme of things, I’m fine. I don’t have cancer or any other more debilitating chronic disease. In a world where so many people suffer from malnutrition, tropical diseases, or profound physical disabilities, it feels a little tacky to whine about being mostly healthy, but not at 100%. I’m healthy enough to do HIIT studio fitness classes at Orange Theory 3-4 times a week. I’m able to travel for work and leisure without difficulty. Most days, I’m pretty content with life. Still, there has definitely been a grieving process knowing that I have lost some measure of myself that I’m never going to get back.

The party line from physicians is that hypothyroidism is easy and simple to treat, with excellent outcomes. From the American Thyroid Association:

“In almost every patient, hypothyroidism can be completely controlled. It is treated by replacing the amount of hormone that your own thyroid can no longer make, to bring your T4 and TSH levels back to normal levels. So even if your thyroid gland can’t work right, T4 replacement can restore your body’s thyroid hormone levels and your body’s function. Synthetic thyroxine pills contain hormone exactly like the T4 that the thyroid gland itself makes.” — ATA Patient Handout for Hypothyroidism

The reality is a lot muddier. Multiple studies indicate at least a subset of hypothyroid patients have poor quality of life (QoL) and dissatisfaction with their care (see: here, here, and here). There could be multiple explanations for this.

First, levothyroxine (synthetic T4) must be converted to T3—the active form—in the body by deiodinase enzymes. Some researchers suspect that patients with autoimmune thyroid disease may have different deiodinase enzyme function, which could explain persistent symptoms despite T4 treatment. This is why some providers treat with both T4 and T3 or desiccated thyroid extract, although rigorous evidence that this practice improves outcomes is minimal.

Second, many patients (myself included) feel like they do better on brand name Synthroid than generic levothyroxine, and endocrinologists seem to agree as they are far more likely to prescribe the brand name than GPs. In the US, the FDA does not require generic drugs to demonstrate their compound is effective, only that it has “bioequivalence,” which is often considered 80-125% the blood concentration of the comparison drug. However, levothyroxine is a “narrow therapeutic index” (NTI) drug, and a 45% difference in levels can be huge. Furthermore, each generic may have different bioequivalence, but your pharmacy can—and does, as I’ve experienced—change generic brands without your knowledge or approval. Some people point to evidence that generics and Synthroid both get a similar proportion of patients into the reference range for TSH, but this is a low bar as that range is widely considered too broad, and patients may have symptoms with changes even inside that interval. Other research shows that patients on Synthroid fare better than those on generics.

Synthroid is much more expensive than the generic, and I have struggled with my insurance company and doctors to prescribe the brand name drug even if I’m willing to pay the difference. I recently gave up trying to fight with them and have settled for an ever-changing generic. My symptoms feel less controlled, but I can’t keep spending hours on the phone, in pharmacies, and filling out forms just to have it reverted back the following month.

Third, all of this assumes a very reductionistic model of thyroid function: “It makes one thing (T4) and giving back that one thing fixes all the problems.” We already know that thyroid function and disease is more complicated than this—it involves multiple hormones in the brain (pituitary gland and hypothalamus), produces way more substances than just T3/T4, and affects virtually every tissue in the body. We still don’t understand the mechanism behind thyroid eye disease and leg swelling (pretibial myxedema), why would would presume we fully understand treating the disease?

Finally, thyroid disease often coexists with mental health disorders (primarily depression for hypothyroidism, anxiety for hyperthyroidism), and there a complex interplay between them that makes establishing cause and effect difficult. Patients with depression are much more likely to report weight gain, fatigue, and chronic pain, so it really does become a question of how much is physical and how much is the mind-body connection.

Meghan O’Rourke sums this up perfectly:

“And so the person suffering from chronic illness faces a difficult balancing act. You have to be an advocate for yourself in the face of medical ignorance, indifference, arrogance, and a lack of training. (A 2004 Johns Hopkins study found that nearly two-thirds of doctors surveyed felt inadequately trained in the care of the chronically ill.) You can’t be deterred when you know something’s wrong. But you’ve also got to be willing to ask how much is in your head—and whether an obsessive attention to your symptoms is going to lead you to better health. The chronically ill patient has to hold in mind two contradictory modes: insistence on the reality of her disease, and resistance to her own catastrophic fears.”

My way of managing this paradox has been to embrace radical acceptance, a concept originating from Buddhism that has been integrated into secular mindfulness that states suffering comes not directly from the pain itself, but from one's attachment to the pain—dwelling on misery makes it worse. Or, in the words of one doctor:

“This may just be how it’s going to be. You may always feel like you’re eighty per cent.”

So I do my best to be compliant with my meds and rechecks, and advocate for myself when something seems off. At the same time, I try to keep reasonable expectations for my health and cultivate the ability to accept and sit with discomfort when it arises, rather than either distracting myself or obsessively ruminating. Everything is constantly changing, pain or fatigue in one moment will often pass if you don’t cling to it. This approach is backed by rigorous science for helping patients with chronic pain and illness.

My health will never be the same, yet I’m OK. I don’t have to like it, but I can accept it. And indeed, that mindset has helped.

Hello from another 80 percenter. In my case the damage, the loss of full functioning, diminished quality of life, and heightened difficulty to get back to non-medically supported life was/is due to Covid and post infection sequelae that were worse than the actual three weeks or so of the disease. I'm into year three now and I often wonder if I might not be still infected, despite six vaccinations and boosters. My story in some ways resembles yours--sometimes the body takes such a hammering that it really never springs back all the way, despite being marvelous self repairer that it is.

But your story is worse, you have it harder than I in so many respects, not the least being you're so young to have this happen to you. At least I was in my seventies when the infection got ahold of me. So I was entering a time of diminution anyway. I'm glad you have Buddhism and it's power to foster acceptance.