AAHA Releases Endocrine Disease Guidelines

Breaking down thyroid and adrenal disease in cats and dogs

Endocrine (glandular) diseases like hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, Addison’s Disease and Cushing’s Syndrome don’t just affect people, dogs and cats can suffer from them too! These diseases impact everything in the body, from appetite and weight to mental awareness and organ function. Early clinical signs may be subtle and non-specific, making them challenging to diagnose. Some patients can be easily controlled on inexpensive generic medications, but others may be challenging to manage. To help veterinarians and owners with these patients, the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) recently released their guidelines on endocrine diseases in cats and dogs, primarily focused on adrenal and thyroid diseases (diabetes is another major endocrine disease and AAHA released those guidelines in 2018). In this article I will walk you through the background of expert guidelines like this along with the key takeaways for the most important endocrine diseases.

A few notes before we get into the weeds:

I am not affiliated with AAHA and had no part in drafting or publishing these guidelines

This article is my take on the most important points from the guidelines, but for practical reasons I could not cover all of the details of the 23-page document. I would direct interested people to check out the full guidelines for more comprehensive information

Because my audience is comprised of both veterinary professionals and people outside the industry, I’ve attempted to distill the guidelines into a post that provides both useful medical information to DVMs/techs and a basic understanding of evidence-based medicine and hormonal diseases to pet owners

This article does NOT constitute medical advice on any individual animal. If you think your cat or dog has a hormonal disease, please take them to your vet!

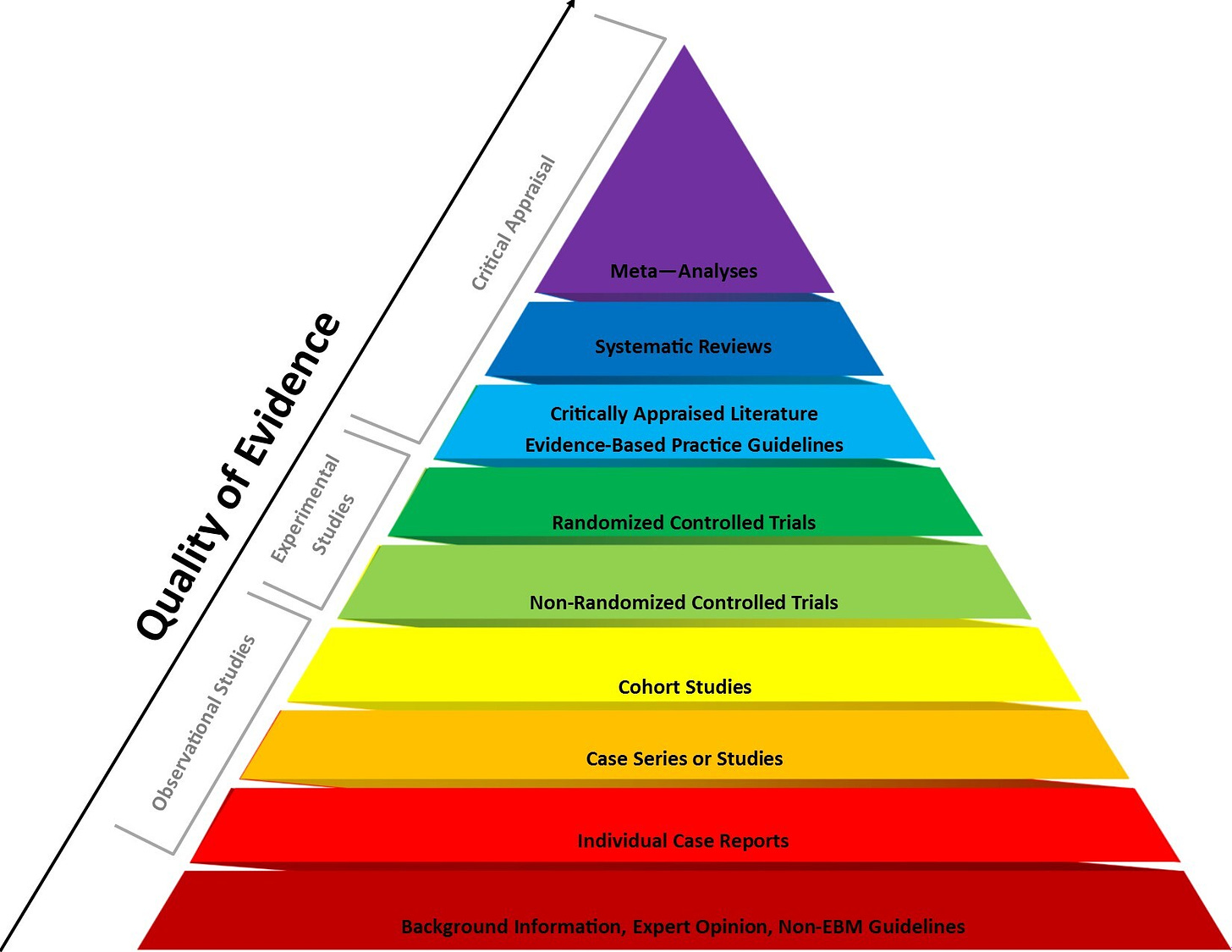

Evidence-Based Medicine

Like science itself, medicine is sometimes more art than science (yes, this is a Rick and Morty reference). It is filled with ambiguous test results, diseases that don’t look like they classically should, patients who don’t respond to the typical treatments, gaps in the medical profession’s knowledge, and complications. Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) strives to mitigate this chaos and treat patients based on rigorous research whenever possible. In this framework, the lowest level of evidence is “expert opinion,” i.e. individual doctors’ decisions based on their own experience. Clinical intuition, while invaluable, is not a substitute for higher levels of evidence because any individual practitioner is limited in the number and type of cases they see and highly prone to various forms of bias and other cognitive errors.

Slightly better evidence than anecdote are basic science studies in model systems (like rats or cells in a test tube), one-off case reports, and non-controlled / retrospective epidemiology studies. Even better are controlled clinical trials, ideally randomized and double-blinded.

The top levels of evidence are systematic reviews and meta-analyses, essentially studies OF studies comparing the results of many similar trials together to determine which results are truly reliable.

How would you assess these guidelines?

These guidelines were written by a panel of experts in endocrinology, internal medicine, and specialized canine and feline practitioners based on their review of the research literature. In the diagram above, I would consider this document to be the third category from the top in light blue: critically-appraised literature and evidence-based practice guidelines. While this tier does not rise to the rigor of meta-analyses and systematic reviews, we often do not have the luxury that human medicine does with large numbers of studies, including replication studies and randomized-controlled trials, on which to create those top two types of evidence.

The majority of the authors are from university veterinary hospitals, and the rest are in independent private practice. None work for the sponsors or declared any financial conflicts of interest. The report was sponsored by multiple companies:

Boehringer Ingelheim

Merck Animal Health

IDEXX

Zoetis

Zomedica

This sponsorship could create the potential for bias, however I judge this risk to be low. First, there are three different diagnostic company sponsors (preventing guidelines that benefit one preferentially), and the hormone tests discussed are long-established assays run by numerous labs, including competitors that are not sponsors. Second, the mainstays of treatment for these conditions—thyroxine, methimazole, prednisone, etc—are available as low-cost generics. The one expensive drug (Vetoryl/trilostane for Cushing’s Syndrome) is sold by Dechra, not one of the sponsors. Finally, these guidelines discuss the problem of over-diagnosis and over-treatment, so if anything, they could stand to lose out by more conservative practice.

Without further ado, let’s get into the specifics of each disease!

Canine Hypothyroidism

Dogs most commonly develop an underactive thyroid due to autoimmune thyroiditis, similar to Hashimoto’s Disease in people. Other causes like malfunctioning signals from the hypothalamus or pituitary gland are extremely rare. Common clinical signs include poor hair coat and/or hair loss, skin infections, decreased energy and exercise tolerance, weight gain, and heat-seeking behavior.

A number of dog breeds appear to be at higher risk for hypothyroidism, including:

Beagles

Doberman pinschers

English setters

Golden and Labrador retrievers

Great Danes

Rhodesian ridgebacks

On the other hand, some breeds are known to have lower thyroid hormone concentrations than normal reference ranges without having any symptoms, particularly Greyhounds and Salukis.

Diagnosis

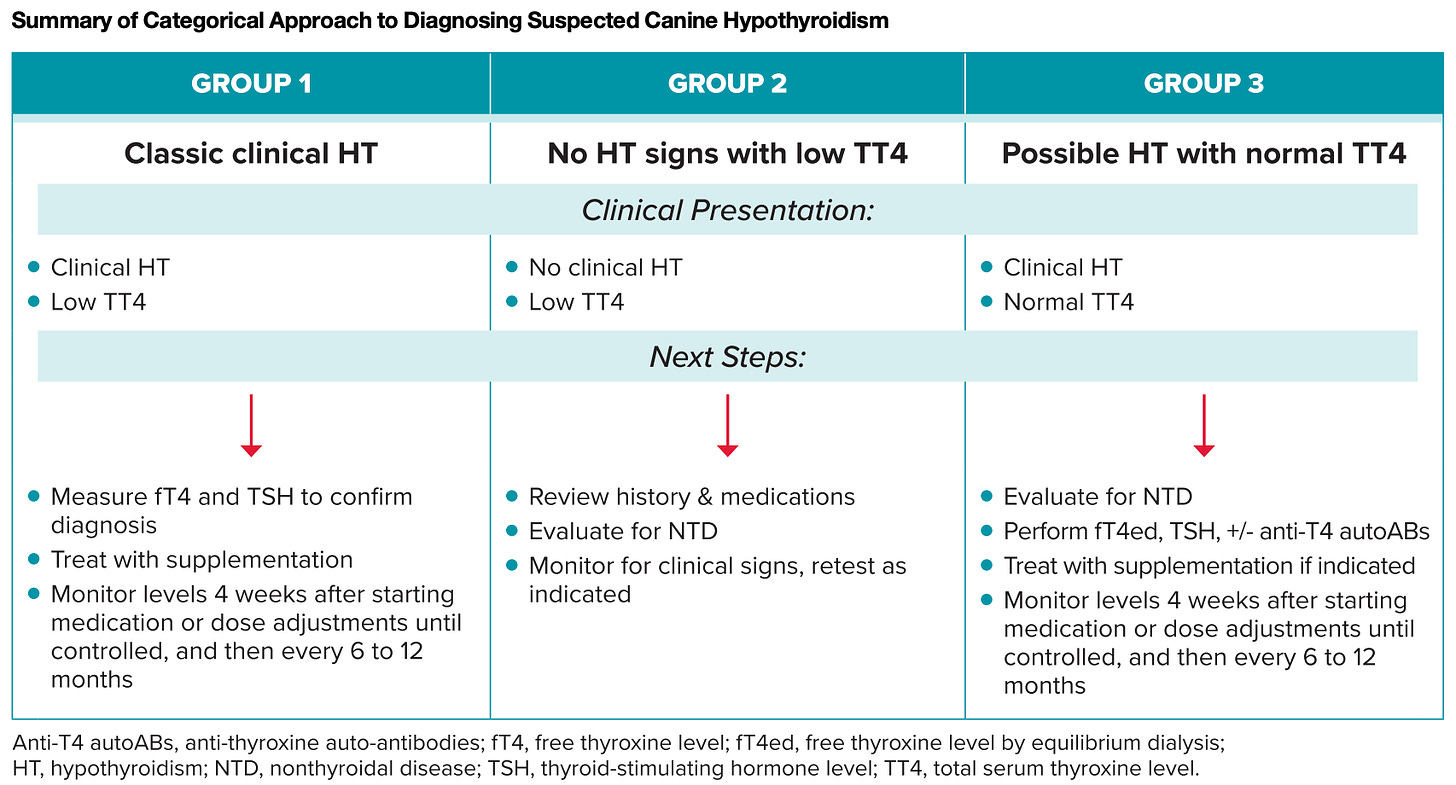

Routine chemistry panel tests may have no abnormalities, although some dogs will show increased cholesterol and triglycerides. Total thyroxine (TT4) levels in dogs with hypothyroidism will be low, so TT4 is often the first screening test. Dogs with a TT4 in the upper half of the reference range are very unlikely to be hypothyroid. However, there are some confounding factors, including age, breed, some medications, stress, and non-thyroid diseases (NTD) that can suppress thyroid function, so the guidelines state:

“An isolated TT4 below the reference interval should not be the only criteria used to diagnose hypothyroidism”

To account for this, there are other more specific tests, including free T4, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), and tests of autoimmune antibodies directed against the thyroid. The table below summarizes the recommendations for different patient groups of possible hypothyroidism:

Management

Hypothyroid dogs are managed by supplementing with levothyroxine. The recommendations are as follows:

Starting dose: 0.02 mg/kg twice a day

Overweight animals may require dosing on lean body weight basis

Medication should be given on an empty stomach (food impairs absorption of T4)

Recheck T4 levels 4 weeks after starting treatment → draw blood 4-6 hrs post pill

Assessment of T4 levels and dose adjustment is based on DVM assessment of clinical signs and hormone levels

Occasionally, complicated cases may require consultation with an internal medicine specialist

Canine Hypercortisolism (Cushing’s Syndrome)

Cushing’s Syndrome (CS) is when excess stress hormone cortisol is produced by the adrenal gland. I am very familiar with it as my dog Jack has been treated for Cushing’s for years now. The two main causes are (1) a pituitary adenoma (benign tumor) that secretes too much adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), signaling the adrenal glands to go into overdrive, and (2) an adrenal tumor that overproduces cortisol. The effects of hypercortisolism are seen all over the body. It frequently triggers excessive thirst and urination, increased appetite, high blood pressure, and panting. These dogs are often pot-bellied from muscle wasting and a swollen liver, they can have hair loss, and they may be overweight. Lab tests may identify numerous abnormalities like increased cholesterol, high ALP (liver enzyme), hyperglycemia, dilute urine with protein in it, and changes to multiple blood cell lines.

Diagnosis

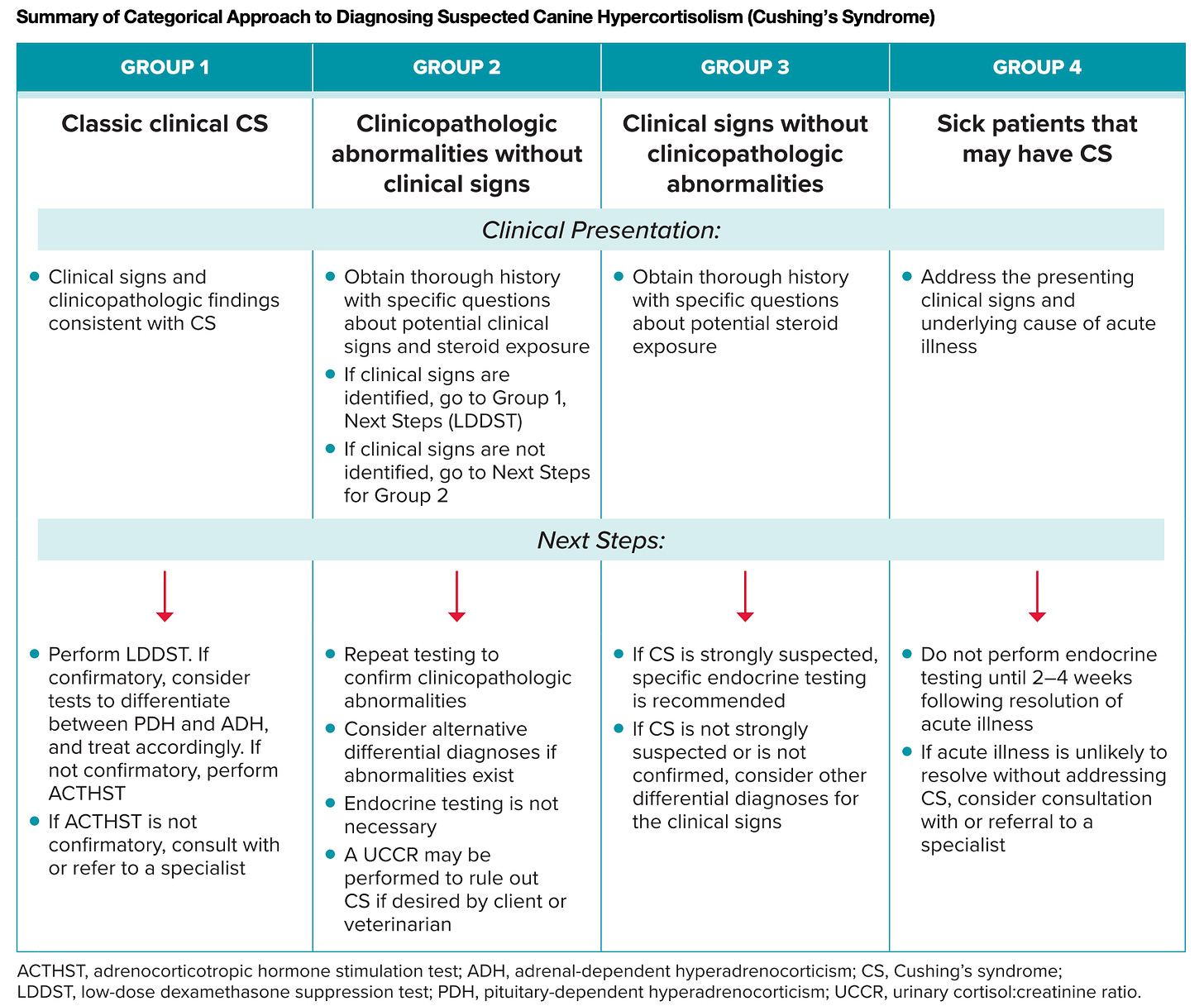

Diagnosis of hypercortisolism is more challenging than hypothyroidism:

“All diagnostic tests for Cushing’s syndrome have limitations and can yield false-positive results when performed in patients with concurrent nonadrenal illness or stress…Practitioners should only test patients when clinical suspicion of CS is high.”

The panel recommended starting with the low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (LDDST) as the first-line test for Cushing’s Syndrome. While it can have false positives from stress or systemic illness like diabetes, an advantage is it can tell the difference between pituitary and adrenal tumor causes of hypercortisolism, which impacts treatment.

The panel recommended the ACTH stimulation test (ACTHST) for the following situations:

Confirming Cushing’s in a dog with high suspicion, but the LDDST was not diagnostic

Confirming hypercortisolism from medications (i.e. prednisone)

Monitoring management of hypercortisolism

The urine cortisol-to-creatinine ratio (UCCR) test is very sensitive, but highly prone to false positives. It is best used to rule OUT Cushing’s syndrome rather than to confirm it when suspected.

Management

Surgical removal is the preferred treatment for adrenal tumors. For owners who decline surgery, and dogs with pituitary adenomas causing CS, there are medications to treat it. Mitotane can permanently destroy the adrenal cortex, but this requires supplementation of the steroid hormones normally produced by this tissue (see Addison’s Disease below). Trilostane is a medication that suppresses production of cortisol, but does not destroy the tissue. Practice pearls from the panel:

The FDA-approved dose is 2.2–6.7 mg/kg/day, but it has been commonly used at lower doses such as 2–3 mg/kg/day

The approved dosing is once daily, but some clinicians find twice daily dosing at a lower dose each time provides better results (this was the case for Jack!)

Monitoring is based on clinical response to medications and the ACTHST

There are multiple published protocols and no consensus on which is the optimum, testing usually begins 2 weeks after starting medication, then a month later, followed by every 3-6 months

Canine Hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s Disease)

Hypoadrenocorticism (HA) or Addison’s Disease is essentially the mirror image of Cushing’s Syndrome—a deficiency of steroids and other hormones like aldosterone (which regulates the kidneys and electrolytes) leads to systemic illness and many of the clinical signs are the opposite of CS. Most cases result from autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex, though sudden withdrawal of steroid medications and a few other diseases can less commonly cause HA. The common presentation is middle-aged female dogs, although any age and gender may develop the condition. Breeds that may be at higher risk include: Great Dane, Portuguese water dogs, and standard poodles. Clinical signs of HA often include dehydration, shock, electrolyte changes (typically low sodium and high potassium), and vomiting.

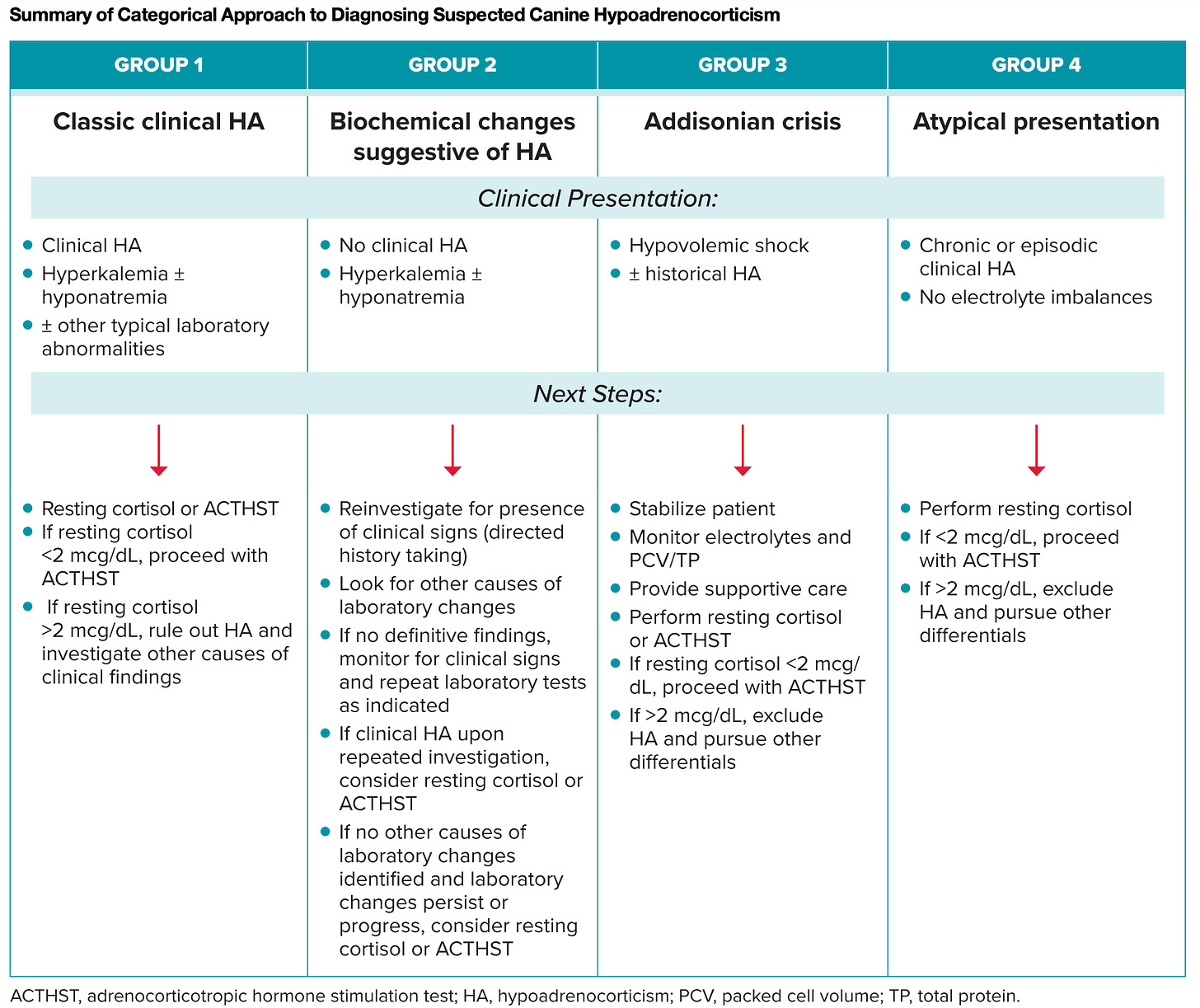

Diagnosis

Remembering to keep HA on the differential list as a rule out is often one of the biggest challenges: Addison’s Disease is often called the “Great Pretender” because it can mimic many different diseases! Likewise, a number of non-endocrine diseases can have similar lab changes to Addison’s, especially kidney failure, whipworms, and severe GI or liver disease.

Confirming a diagnosis of HA requires the ACTHST discussed in the section for hypercortisolism, except the results will show low cortisol that fails to appropriately increase in response to ACTH stimulation. HA can almost always be ruled OUT by a single baseline cortisol of > 2 mcg/dL.

Newer tests like endogenous ACTH, cortisol:ACTH ratio, and UCCR may be useful in the future, but there is less data on them and they are not as widely available.

Management

Since HA is deficiency of steroids +/- aldosterone, these hormones must be replaced:

Prednisone/prednisolone

The dose for physiologic replacement is much lower than the doses used to control inflammation or immune-mediated disease (<0.25 mg/kg/day)

Doses may be as low as 0.1 mg/kg/day

Dosing is adjusted based on clinical signs and response to treatment

Desoxycorticosterone pivalate (DOCP)

This replaces the function of aldosterone

The labeled dose is 2.2 mg/kg, but as little as 1.1-1.5 mg/kg may be effective

Dosing is adjusted based on electrolytes and clinical signs

Feline Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism in cats is almost always caused by a thyroid nodule or benign adenomatous hyperplasia that produces too much T3 and/or T4, unlike in human medicine, where autoimmune Grave’s disease that causes the whole gland to malfunction is the most prevalent. Feline hyperthyroidism is common, and typically leads to weight loss despite ravenous appetite, increased heart rate and blood pressure, increased thirst and urination, GI signs, and abnormal behavior (usually increase in aggression). When a middle aged to older cat is losing weight and urinating more frequently, your vet will immediately begin evaluating the possibility of hyperthyroidism, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease (although there are many other possibilities, these are among the most prevalent).

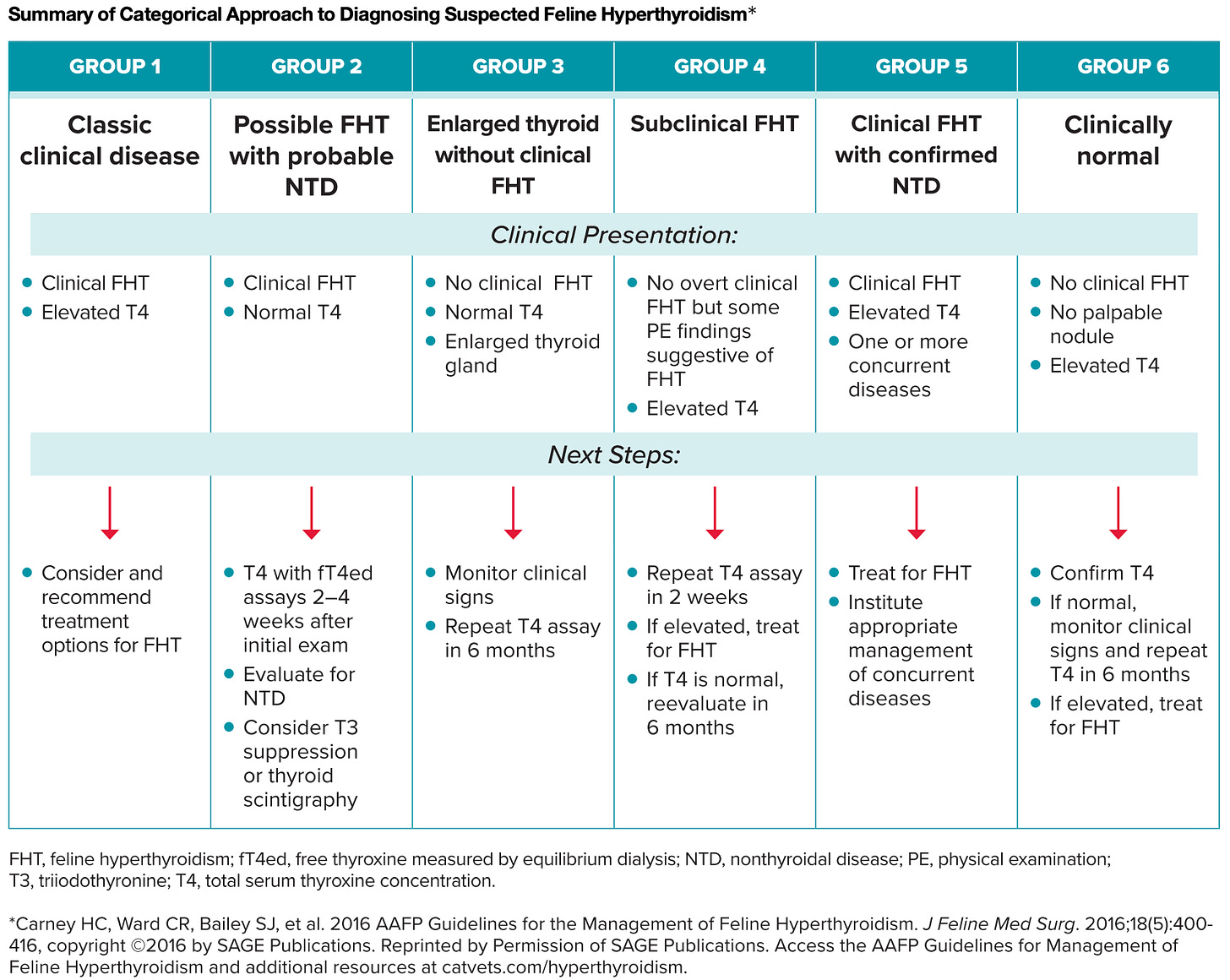

The AAHA guidelines for endocrine disease specifically reference the 2016 American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) Guidelines for Hyperthyroidism as largely still accurate and useful, with some tweaks and commentary.

Diagnosis

Many cases of hyperthyroidism in cats are straightforward to diagnose. Cats will often have most or all of the classic signs plus an elevated total T4. Since non-thyroid disease can suppress TT4, free T4 may be useful in cases that are not as straightforward. For more complex cases, adding in TSH can help catch early or subclinical cases, although it cannot be used on its own (unlike human medicine, where a more advanced and sensitive TSH assay is the primary test for diagnosis and monitoring).

Management

There are multiple different treatment options for cats with hyperthyroidism. The #1 recommended treatment, like in people, is radioactive iodine, which leads to a permanent cure in >95% of cats. However, this may not be available in some areas, and the cost may be prohibitive for some owners. Surgical removal of the thyroid gland is another option, but carries significant cost, requires anesthesia, and has a higher risk of complications.

The #1 recommended treatment, like in people, is radioactive iodine, which leads to a permanent cure in >95% of cats.

Another popular option is using the drug methimazole to suppress thyroid hormone production. The recommendation is to start at a low-dose (typically 1.25-2.5 mg/day) and gradually increased to the point where remission is achieved. Cats on methimazole will need to have their T4 levels periodically checked to adjust dosing, particularly to avoid overcorrecting and creating a hypothyroid cat.

Prescription iodine-restricted diets can be effective in controlling hyperthyroidism in some cats, although for it to be effective the cat must not eat any other food or treats. It will generally take longer (months) to get control of thyroid disease with diet compared to the other treatment options above. Other cats can safely eat the prescription iodine-restricted diet if they can’t be separated for meals.

Take Home Messages

In conclusion, adrenal and thyroid diseases are fairly common in cats and dogs. They may be challenging to diagnose and manage, but most patients have a high probability of a long and good quality life following these guidelines. For best outcomes, collaboration between owners and the entire veterinary care team is key. The figure below summarizes some of the main points:

Tell me in the comments what you think about the new guidelines, and if you have any experience with these diseases!

Your summaries and tid bits are super helpful as I don't often have time to read a whole guideline or article but the information you pick out is always helpful and focused on key clinical necessary points. Really appreciate your efforts and focus. Ty

Really fantastic summarization! Technical but not overwhelmingly so. This is a gift for all pet owners. Thanks for the hard work you put into a jewel of concision and an example of how to pack a truckload of information into a small cargo bed.