Book Review: Slow Productivity

The high priest of "Deep Work" wants to save knowledge work from itself

Dear Readers,

I generally hate self-help books and tend to avoid them like the plague. They are often overly simplistic and patronizing. The worst offenders are those “grindset” bros that promise ways to boost productivity, as if any of us aren’t banging on all cylinders and doing too many things already. So, it might seem odd that today I will be reviewing a self-help book that literally has productivity in the title.

However, Cal Newport is not your average LinkedIn influencer pushing cheesy work “hacks,” and his new book Slow Productivity is not your typical banal business fare. He is a prolific computer scientist and author of many books and New Yorker articles. Newport’s writing occupies a space that could best be described as the intersection of culture, economics, technology, and psychology (particularly boundaries and mindfulness).

I have been following Newport’s work for years after a friend turned me on to his earlier book Deep Work, which preached the virtues of blocking out modern digital distractions to focus on the things that matter most to us. Like fellow tech critic Nicholas Carr in his book The Shallows, he makes the compelling case that one of our most precious—and undervalued—resources is our attention; if you don’t believe him, consider the fact that the most valuable companies in the world (think Apple, Meta, Google, Netflix, Amazon, etc) all monetize your attention through digital ads and/or subscriptions to addictive apps and streaming services. Newport is famously not on social media and urges people to re-evaluate their relationship with email, smartphones, and many other electronic tools, not only for better productivity, but also to reduce stress and reclaim some of our humanity.

Reading his newest book was both enjoyable and yielded immediately useful lessons for my daily life. I hope this review convinces you to check it out as well.

—Eric

“Pseudo-Productivity” vs. A Better Way

For Newport, the ideas for Slow Productivity began crystallizing in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. As lockdowns shuttered offices and many white collar “knowledge workers” shifted to remote work, many people began to spend longer and longer hours in front of screens. Managers couldn’t see their direct reports anymore, but they could still ping them over email, and text, and Slack, and Zoom, and countless other digital avenues.

The workday, once clearly delineated in time and space, began to consume mornings and nights, with people working throughout the day and sneaking in tasks and calls throughout any downtime, 7 days a week.

PowerPoint decks and meetings (and meetings to plan meetings!) became proxies for getting stuff done. After all, you couldn’t be loafing if your Outlook calendar is stuffed to the brim and your colleagues saw you on video for hours every day, right? Right???

These folks (myself included) initially considered themselves at least lucky to still have jobs and to be safe from the novel virus ripping around the world. But overtime, the cracks began to show.

You would see headlines about “Zoom fatigue.”

Next came “The Great Resignation.”

Then Gen Z had enough, triggering a mass panic over “Quiet Quitting.”

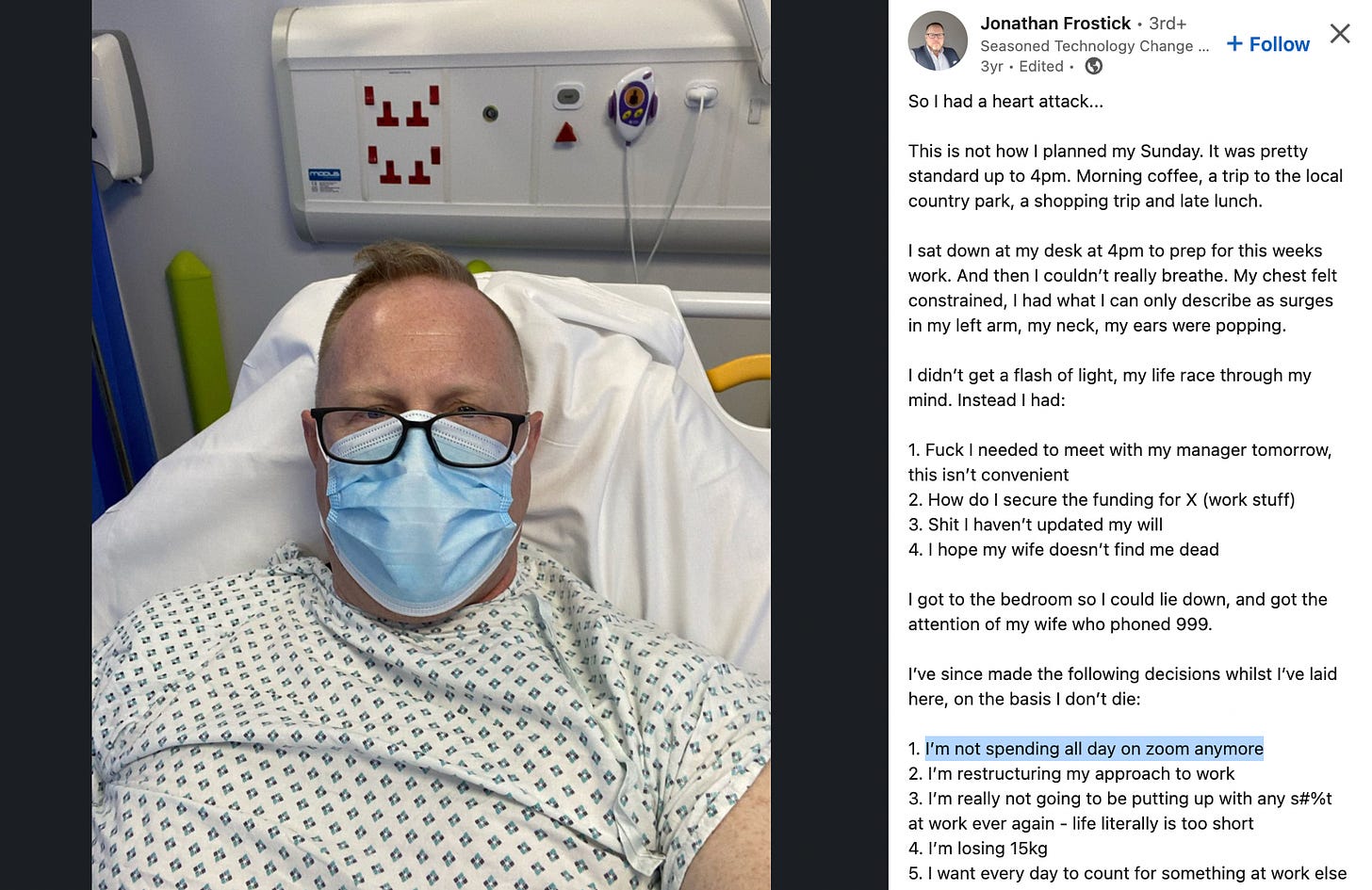

Newport highlights a particularly stark example of the phenomenon with the story of Jonathan Frostick. He was an IT manager in the UK who struggled with that kind of excessive remote work and it literally gave him a heart attack. Fortunately, he survived, and his LinkedIn post about the experience went viral:

Newport dubbed this endless barrage of communication and electronic box-checking “pseudo-productivity.”

PSEUDO-PRODUCTIVITY:

The use of visible activity as the primary means of approximating actual productive effort

While the pandemic definitely accelerated the ubiquity and severity of pseudo-productivity, it didn’t create it originally. Newport explores the history of how “knowledge work” had long struggled to accurately define and measure productivity the same way as factories did during the Industrial Revolution.

Obviously, Henry Ford could measure how many cars he produced a day and work to optimize the steps that maximized that number. But how does one determine if a computer programmer or professor or senior manager is being productive or not? You could measure lines of code written, papers produced, or number of presentations to assess performance, but all of these are imperfect and possible to manipulate.

The default heuristic became “how busy does it seem like they are?”

There has to be a better way.

Cal Newport began thinking deeply about this problem, researching examples of people who led unequivocally productive lives and trying to find lessons in their success. He draws on such diverse people as scientists like Isaac Newton to the prolific writer John McPhee to Lin-Manuel Miranda. In trying to distill what he discovered into a coherent philosophy, he took inspiration from the Italian “Slow Food” movement and the food writer Michael Pollan’s simple yet powerful advice:

In a similar vein, Newport offered his alternative to pseudo-productivity he dubbed “Slow Productivity” 👇

SLOW PRODUCTIVITY:

A philosophy for organizing knowledge work efforts in a sustainable and meaningful manner, based on the following three principles

1. Do Fewer Things

2. Work at a Natural Pace

3. Obsess Over Quality

About 75% of the book covers those three areas, and I will discuss some of the highlights below.

All Science Great & Small is a reader-supported guide to veterinary medicine, science, and technology. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription 👇

Do Fewer Things

This is probably the most provocative of Newport’s arguments. How in the world could you get more done by doing less??

He starts with the example of the Victorian novelist Jane Austen, who wrote classics like Sense and Sensibility, Mansfield Park, and Pride and Prejudice. The story of how she wrote them is commonly told that she frequently scribbled notes and fragments of the books whenever she had a free moment in between entertaining guests and maintaining the house. If anything, this would seem to support the “hustle culture” mindset of always working 24/7.

But as it turns out, that is not quite accurate. More recent biographies, drawing from primary sources including journals from Austen and her family, indicate that it was not until she committed to finishing her novels and her family agreeing to free her of the many chores and social duties expected of women at the time that she made any substantial progress. Once she was given less to do, she completed multiple groundbreaking manuscripts within a few short years.

How does this apply to a modern office worker? The argument is actually pretty simple: for each project or task you take on, you are also taking on a dose of “administrative overhead” such as recurring meetings, asynchronous document editing, and endless back-and-forth emails and Slack messages.

He uses some simple back of the envelope math to illustrate the point. Imagine you produce market research reports. If each one takes 7 hours with 1 hour of overhead, you could get five done per week if you took on one at a time and completed them sequentially. On the other hand, if you agreed to do four of those projects at once, now half of every 8 hour day would be consumed by that overhead, not even counting the time costs associated with frequent task switching. In the second scenario, you would optimistically only hope to get 2-3 reports out per week!

He has numerous suggestions for how to do fewer things. One of them is “Contain the Big”; essentially narrowing the focus of your efforts at different timescales, from broad “missions” (in his case writing and computer science research), to specific projects that might take weeks or months, to short-term tasks. After reading this section, I decided to take an inventory of all of my commitments to see how my time spent aligned with what was most important to me:

What I found was eye-opening—While I wanted to focus most on diagnostics and writing, I had agreed to many other missions and projects that were pulling me away from them, slowing me down and adding a lot of stress. I had several takeaways:

I was working towards too many missions (Newport recommends 2-3 max) and far too many projects

I definitely did NOT have the bandwidth to launch and support a planned coaching service

Action Items

Don’t agree to any more speaking arrangements in 2024

After completing ACVP/ASVCP projects in progress, pause committee work

Continue to modestly reduce time and travel-intensive locums and increase my focus on writing and contract work

This section has many other great suggestions, including implementing ways to have others do more work up-front when adding tasks to your plate to improve clarity and efficiency and moving to a “pull” workflow instead of a “push” workflow, a concept pioneered in assembly lines and adapted to knowledge work sector by organizations like the Broad Institute genome sequencing lab.

Work at a Natural Pace

The second tenet of “Slow Productivity” advises we slow down and take cues from our body and environment to determine when and how to work. Cal Newport introduces the story of the composer and playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda of Hamilton fame. He famously wrote and first performed his blockbuster musical In the Heights while an undergraduate at Wesleyan University. The impression people get from that story is one of a prodigy who burst onto the theatre scene fully formed.

The reality is a lot more nuanced. In fact, he first wrote Heights in 1999 and it debuted on campus in 2000 to mediocre reviews. Critics found the plot and dialogue was cliche and uninspired, but everyone was impressed with the unique score that fused hip-hop with salsa and more genres. After graduation, Miranda set aside that musical and bounced around doing various projects and odd jobs, including working as an English teacher, writing newspaper columns, and composing jingles for commercials. In between these distractions, he would periodically return to Heights, collaborating with others to improve the script.

It finally premiered on Broadway in 2008, nearly a decade later, to universal acclaim, including winning the Grammy for Best Musical Album and 13 Tony Award nominations (Miranda himself won the Tony for Best Actor). Lin-Manuel Miranda certainly took his time through frequent pauses and detours, but the work speaks for itself.

Miranda is not the only one with a story like this. Newport sheds light on the famous story Jack Kerouac himself told about completing the draft for On the Road in a mere three weeks; it turns out that was a bit of clever self-mythologizing—he spent years before that burst of writing formulating ideas and fragments, and after that initial draft, it took almost as long to edit and revise it into the final form. Cal shares more examples like that of Sir Isaac Newton, whose Principia Mathematica revolutionized math and science, yet took almost 30 years to finish, despite the classic story about a flash of insight from a falling apple.

To some, such snail-like progress on projects may come across as a lack of commitment, or worse, laziness. However, there are good neurobiological reasons that explain why creativity and inspiration take time. Our brains require downtime to integrate all of the information we ingest constantly to make sense of it and reinterpret it in novel ways. One part of the nervous system that does this is called the default mode network:

“The default mode network (DMN) is a system of connected brain areas that show increased activity when a person is not focused on what is happening around them. The DMN is especially active, research shows, when one engages in introspective activities such as daydreaming, contemplating the past or the future, or thinking about the perspective of another person. Unfettered daydreaming can often lead to creativity. The default mode network is also active when a person is awake. However, in a resting state, when a person is not engaged in any demanding, externally oriented mental task, the mind shifts into “default.”

I can attest to this phenomenon as some of my best research and writing ideas have come on long cross-country drives that allow my mind to wander.

In addition to taking longer, Newport suggests several other strategies, like embracing seasonality (alternating intensive “sprint” periods with less busy downtime to recover) and getting out of your regular environment to alter your thought process.

Obsess Over Quality

The final section is anchored by a powerful anecdote about the singer-songwriter Jewel. Prior to her breakout album Pieces of You, she was a starving artist—literally. She was homeless in San Diego and living out of her car while she hustled to find gigs for anyone who would listen (and ideally pay).

During this period her shows at a local coffeehouse became popular, and she started drawing crowds. Eventually, scouts from major record labels discovered her and she was offered multiple lucrative contracts, including one with a signing bonus for $1 million.

She turned it down.

How could someone who was homeless turn down that much money?!

Jewel had done her research, and she learned that such contracts were often structured so that “bonus” was more of a loan, and record labels could drop the artist if they didn’t quickly deliver a return on that initial investment. She crunched the numbers and decided that it would be very difficult to deliver financially. It would essentially force her into bland, radio-friendly pop singles that clashed with her artistic sensibility.

She went with a different producer who was aligned with her vision and accepted lower pay, which gave her the breathing room to hone her talent and her voice. Jewel discarded the over-polished and soulless recordings of her early songs pushed by major label producers. She stayed true to her self, and when Pieces of You finally came out years later, it was one of the best selling debut albums of all time. She has since sold tens of millions of albums.

The lesson here is decidedly not “sacrifice everything to be an artist, it will definitely work out and you’ll become rich.” Rather, it is a testament to betting on yourself and maintaining a laser focus on quality. There’s no way to know what would have happened if Jewel took the quick payday, but I suspect there’s a good chance half-heartedly churning out bland music that her heart wasn’t in would have left her like so many other One Hit Wonders: broke and forgotten.

Cal Newport highlights many other less dramatic examples than famous musicians, including a freelancers that dared not to scale their business at the expense of quality, leveraging their reputation for excellence into more freedom rather than chasing riches.

As he brings the book to a close, Newport argues that this obsession over quality is the most important tenet of the three to produce meaningful work that stands the test of time, yet the first two are necessary to make the third possible. Some of the specific strategies and tactics he writes about were new to me, although I found that I have employed the general principle throughout my career. Whether it is my academic research, diagnostic pathology reports, or creative non-fiction writing, I may not be the fastest or most “productive,” but I’m damn proud of what I’ve put out into the world.

Closing

Slow Productivity is a shot across the bow that challenges the status quo of the modern workplace, which is more important than ever as the rates of anxiety, burnout, and depression soar. One of the book’s strengths is its practicality. Newport offers actionable advice on how to transition from a fast to a slow productivity mindset, including how to set boundaries, reduce distractions, and create a work environment conducive to focused and meaningful work. He also addresses potential challenges in adopting slow productivity, such as resistance from organizational cultures.

Critics of Newport’s book might argue that the concept of slow productivity is a luxury not feasible in all professions or industries where quick turnaround times are essential. Indeed, he calls out the challenges that may be faced by working parents and some types of jobs. However, Newport counters this by highlighting that even in fast-paced environments, a more reflective and considered approach can lead to better results and more sustainable work practices. His call for a slower, more deliberate approach to work is not just a productivity strategy but a cultural critique, arguing persuasively that there is a better way that can lead to deeper satisfaction and regaining out sanity.

Great review! I did this kind of assessment and mission identification as a junior faculty member, and it made a big difference in how I thought about my days. I started reserving the mornings for work that mattered most, and I limited travel to once a month. I like Newport but I do share some of the concerns that he is writing from a pretty privileged space—no child or elder care, able to decide where to put one’s energy, etc.—but I agree that everyone can get something useful out of his work!

Dissenting opinion here! Please don't hate on me overly (or at least more than you think I deserve.)

Our minds are adaptive. They got to be the way they are via our individual histories. They are each very tightly inter-effecting. Change one aspect and the effects are not localized. Ones current organization is the way it is for a reason. Wrenching changes or monkeying with the setup can be hazardous in unexpected ways, or temporary patches that quickly revert to a status quo ante. On reform programs in general I counsel incremental approaches. Let the mind slowly reorganize itself to s new stable equilibrium. But always be cautious- "beware what you ask for.."