This continuing education article was originally written by me for the VetHive learning and support community where I am a pathology guide and content creator. Thanks to Dr. Kate Baker for permission to cross-post this material to All Science Great & Small!

One of the first concepts taught in cytology is “atypia” or “criteria of malignancy.” These are features of abnormal cellular division such as anisokaryosis, multinucleation, abnormal nucleoli, pleomorphism, mitotic figures, and more. A classic rule of thumb states that three or more criteria of malignancy can help you differentiate between normal tissues and cancer.

However, like many things in pathology, these simple rules don’t always pan out. Some features of atypia are relatively weaker or stronger, and this can vary by tissue type. Tumors don’t always read the book, and some may only have one or two abnormal features. There are some cases where tumors appear cytologically well-differentiated but show histologic features of malignancy like tissue invasion or metastasis. Finally, there are cases where benign lesions may look quite abnormal on cytology, but there are non-malignant explanations.

Below are several examples of when lesions “break the rules” to help you move beyond the basics and up your cytology game!

When cells look ugly, but are actually benign

Normal or hyperplastic liver

The liver is a highly active organ that is constantly synthesizing proteins, removing drugs and toxins, and producing bile to metabolize lipids. To respond to these frequent demands, hepatocytes must enter the cell cycle and proliferate, which can create the common incidental finding nodular hyperplasia. A side effect of this process is many hepatocytes are binucleated (rarely trinucleated) on cytology and histology. Despite multinucleation being a strong criterion of malignancy in most cases, it is generally disregarded on liver cytology, unless it is extreme and accompanied by other features.

Reactive fibroplasia

Evaluating spindle cells on cytology is the bane of many clinical pathologists because they can be present in high numbers and appear abnormal in many conditions besides mesenchymal neoplasia. Chronic inflammation can provoke reactive fibroplasia in conditions ranging from a ruptured keratin cyst or sebaceous adenoma to a vaccine reaction, panniculitis, and much more. Many types of NON-mesenchymal tumors can also cause irritate surrounding connective tissue and induce a profound spindle cell proliferation called a scirrhous reaction or desmoplasia, particularly mast cell tumors and carcinomas. Atypia in these instances can be quite profound. Virtually all clinical pathologists who have practiced for any length have time have been burned at least occasionally by diagnosing a presumptive sarcoma that ends up being a non-neoplastic mesenchymal proliferation on biopsy. This is why many cytology cases with inflammation or mixed populations that include spindle cells end up with a cautious, equivocal report.

Dysplastic squamous epithelial cells

In a similar vein to reactive fibroplasia, inflammation can damage epithelial cells and cause cellular changes that mimic cancer. One of the most common changes is increased cytoplasmic basophilia as cells increase RNA manufacturing repair proteins. They can also begin to show anisocytosis and anisokaryosis, and less often multinucleation. Squamous cells in particular are prone to dysplasia. Complicating matters further, longstanding epithelial dysplasia may eventually turn into neoplasia.

Mammary Tumors (Part I)

Canine mammary tumors are almost 50/50 benign and malignant, and differentiating them on histopathology can sometimes be challenging, let alone on cytology! One of the problems that arises is there is often minimal correlation between degree of atypia and biological behavior. Cases of a mammary adenoma or low-grade carcinoma without significant metastatic potential can have wild cytology with every criteria of malignancy under the sun, but on histopathology they are well-confined within a capsule and show no signs of invasion or metastasis.

When cells look healthy but are secretly evil

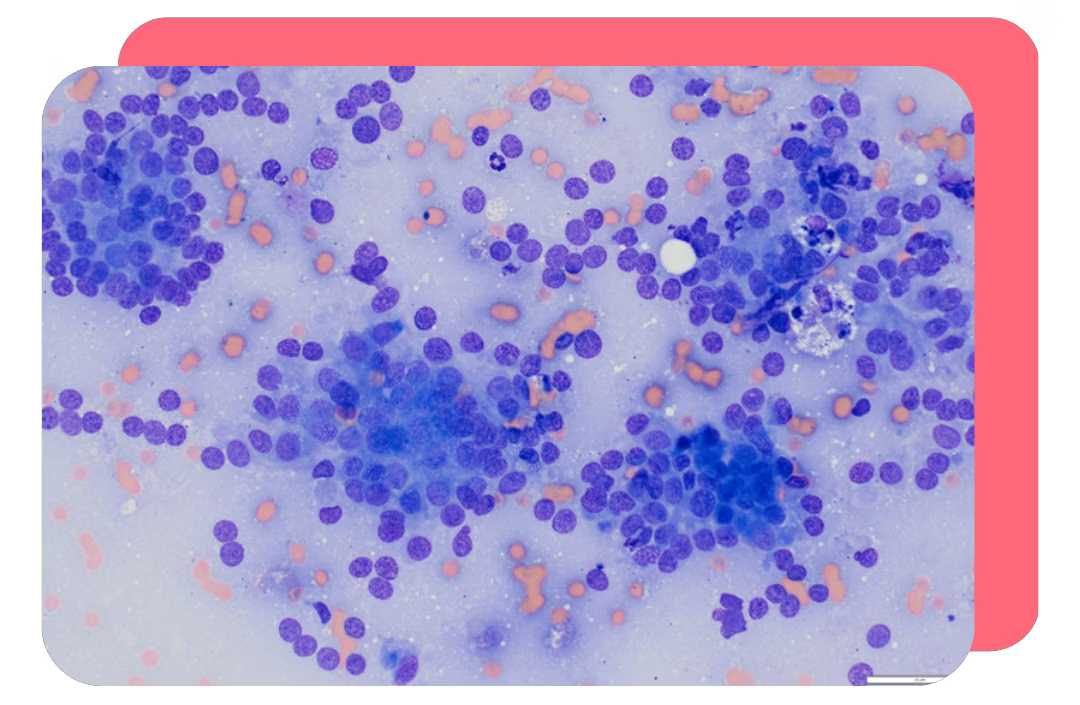

Lymphoma

Lymphoma (and to some extent round cell tumors in general) breaks the fundamental rule of atypia where the more variation in cells you see (anisocytosis and anisokaryosis) the more likely the sample is cancerous. In normal or reactive lymph nodes you expect to see a mix of lymphocyte sizes and morphologies, whereas in lymphoma you lose diversity and see a homogenous expansion of large lymphocytes. In addition, small mature lymphocytes have about the highest nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (N:C) around, while lymphoma cells have increased amounts of deep blue cytoplasm, meaning they have a lower N:C.

Neuroendocrine tumors

Neuroendocrine tumors classically show little to no atypia and look bland on cytology. If you’re looking for giant nuclei, lots of variation, abnormal nucleoli, and multinucleation, you’ll be sorely disappointed. But unfortunately, many of these tumors, including thyroid carcinomas, apocrine anal sac adenocarcinomas (AGASACA) and insulinomas are biologically aggressive and metastasize readily. The key is to recognize the classic “neuroendocrine” pattern on cytology and remember the underlying biology of the specific tumors.

Mammary tumors (part II)

The flip side of mammary tumors with atypia being benign is that some mammary carcinomas can have cells that appear small and uniform. In fact, bland-appearing micropapillary and “triple negative” or basal-like mammary tumors in women and dogs have among the shortest survival times and resist most forms of chemotherapy. Because of this dynamic, mammary cytology should be employed cautiously, and mostly to (a) stage patients by FNA of draining lymph nodes when the primary tumor has been diagnosed and (b) to rule out other pathologies in the mammary gland region, such as an abscess or other type of tumor.

Final thoughts

Reading this article may have given you some heartburn as the canonical rules of cytology seem turned upside down. But fear not, they still hold much of the time and will guide you well! As the expression goes, “the exception proves the rule.” Hopefully, by knowing some of the situations where the rules are broken, you will be able to recognize when to apply the classic criteria of malignancy, and when the tissue/lesion type does its own thing.