Crazy Orange Cats

Are the rumors about wild ginger cats true?

I’ve previously written about the science of cat coat color from the angle of the color point gene mutation. Today I want to talk about it from the behavior side. Anyone who has owned or known an orange cat knows they’re a bit… different than other cats. Many people consider them friendlier and more affectionate, and more than a few report they tend to be wilder and more playful.

Here are just a few quotes from a Reddit thread on the subject:

“My ginger cat is obsessed with my feet. I'll be asleep all comfy and in a good dream then bam! I'll be woken up cause my kitten has decided to randomly bite my toes in the night”

“Yeah my orange cat is still a kitten but you can already tell he’s gonna be an odd bird. He licks windows and tries to nurse his brother.”

“My mother in law's orange cat is obsessed with hands. He watches how people's hands work and imitates behaviors and mechanics. He picks up all of his food with his front paws. He has incredible dexterity.”

“Mine got mad at me the other day and went somewhere and came back with a whole Ritz cracker. I'm still not sure where she pulled it from. She went right to the middle of the room, crushed it into crumbs and then walked away. She knows I hate that.”

My own orange cat Ernie is a complete maniac, literally swinging from the hanging lights in our kitchen! He also loves to bite toes and do weird things. You can see for yourself in this video of him spinning chasing his own tail:

But is there any actual science to back up these claims? After all, the plural of anecdote is not data, and we know there are baseless stereotypes about personality based on hair color in people. Let’s take a look!

People are more likely to rate orange cats as friendly

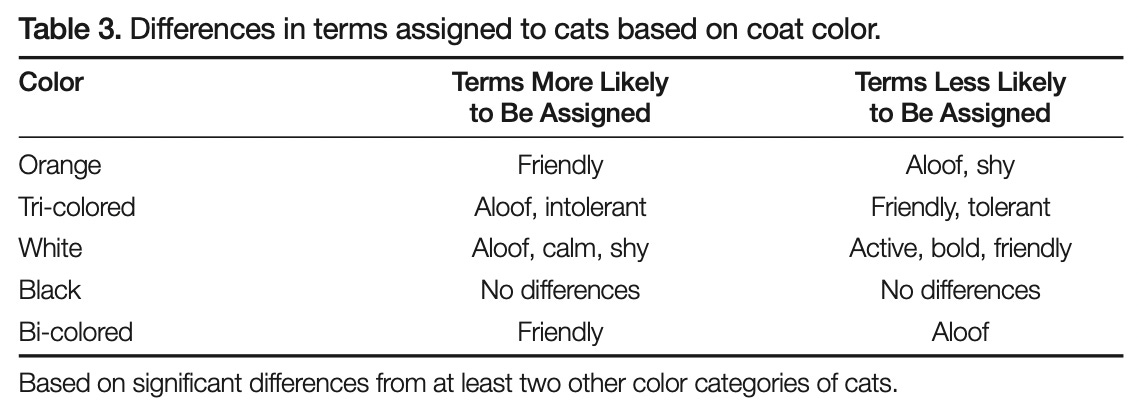

One study in 2012 evaluated how people perceive cat behavior by coat color. Researchers at UC Berkeley asked 189 people to rank terms they would associate with different types of cats, rating descriptors like “friendly,” “aloof",” and “stubborn” on a 1-7 scale. People were significantly more likely to describe orange cats as friendly than white, black, multicolored, etc.

Unfortunately, they did not specifically ask about descriptors like “maniac,” “window licker,” or “toe biter”! Science will have to address those shortcomings in a future study 🤔

So it seems like there is some documented support for this perception (although a different study looking at cat behavior in shelters did not find coat color was associated with aggression). Why might this be the case? There are a few possibilities.

Orange cats are more likely to be male

There are several genes that determine the characteristics of a cat’s fur coat. Some control patterns of striping, color dilution, and other factors. One of the most important for color has co-dominant (equally strong) alleles, or versions, that code for either phaeomelanin, a reddish brown color, or eumelanin, which is a brown or black pigment. This gene locus is found on the X-chromosome, so there is a sex-linkage. As the simplified diagram shows below, since male cats have only one X-chromosome (the other being the Y chromosome that determines male gender), the two main color options for cats are ~50% orange and ~50% brown or black. Female cats have two X-chromosomes, so they have more possibilities: Two black/brown pigment genes, two reddish-orange pigment genes, OR a mix of colors.

One of the two X-chromosomes in every cell in females is randomly inactivated (to prevent over-expression of certain genes), so in female cats with mixed color genes they will have patches of fur that are orange and others that are brown-black, the classic tortoiseshell or calico pattern.

[A very rare exception are male cats that have XXY chromosomes (Klinefelter syndrome in people) that can be calico-colored, and they are usually sterile].

Looking at the math above, a male cat has about a 1 in 2 chance of being solid orange, while for female cats it is about 1 in 3. This is over-simplified, but explains why other factors aside, a solid orange cat is more likely to be male than female by about 50%.

Addendum (from Dr. Bruce Smith): “The issue is allele frequency. The latest data I have seen, which is quite dated, shows that the "orange" X allele frequency in the US is about 10%. That means, since male cats only need one X, that the frequency of orange male cats is also 10%. Since an orange female cat would require TWO "orange" X's, the chance of an orange female cat is the PRODUCT of the allele frequencies or 0.1 * 0.1 which is 0.01 or 1%. So the chance of an an orange female cat is about 10% of that of an orange male cat, and orange female cats, at 1% of the female population are quite rare.”

Male cats may be friendlier

How does the gender skew connect to behavior? Ask a veterinarian about cat behavior and many will tell you that (neutered) males tend to be friendlier and more chill than female cats. This anecdotal impression has some support from a 2015 study at UC Davis. This one was much larger than the 2012 Berkeley study—they asked 1,432 cat owners to fill out a survey about their cat’s behavior, coat color, and demographic information.

They initially found that owners of female cats were significantly more likely to report aggression towards humans than owners of male cats, although that finding was non-significant when they analyzed multiple variables, including coat color. In multi-variable analysis, female tortoiseshell/calico cats were rated much higher on the aggression scale, which skewed the overall female group. When it came to handling specifically in veterinary offices, female cats as a whole were scored as significantly more aggressive by their owners.

The authors of the study concluded:

“These findings suggest that increased aggression toward humans may exist among sex-linked females, gray-and-white cats, and possibly black-and-white cats compared with cats of other colors. The finding that tortoiseshell/calico/torbie cats were significantly more frequently aggressive toward humans supports the contention that calicos and tortoiseshells can be challenging for some guardians. Because aggression is usually multifactorial, some aspects may be related to specific X inactivation that creates the coat-color patterns of these females. Increased aggression among black-and-white and gray-and-white cats compared with cats of other colors was not expected.”

Orange male cats may employ a different reproductive strategy

One study in France found that the orange color gene was much more prevalent in rural areas than densely populated urban areas. In rural areas, there is a predominance of female cats and relatively less frequent male cats. This is in part due to all types of males being more likely to be hit by vehicles, eaten by predators, and shot by humans out in the countryside compared to cities. The few tomcats tend to mate with large numbers of females (polygynous reproduction), so something about orange males must make them more successful in this environment. Orange males tend to be larger than other colored male cats and aggression is correlated with weight and size, so perhaps they may be physically dominating to win over queens. There may be an impact of their unique personality/behavior as well, as it could be the case that other traits are co-inherited with the orange color gene on the X-chromosome.

On the other hand, in cities with many feral or non-owned cats, there are far more males and orange cats make up a lower percentage of the total. Queens there are promiscuous and mate with many tomcats. In this environment, orange cats are less successful. One possible explanation is that the greater tendency towards fighting and risk-taking hurts their survival and females have far more choices for mates. Non-orange tomcats in this setting may benefit more from sperm competition or other reproductive traits rather than simple physical dominance.

There is some support for this notion as a study of feral cats in Italian cities found that 78% of litters had multiple fathers (due to queens being induced ovulators who can be fertilized at different time points). The males who sired the most kittens were, on average, more socially dominant, larger in size, and more likely to be infected by Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV, which is usually transmitted through bite wounds from fighting). As the authors state, “[this study ] shows that the reproductive benefit associated to rank may be balanced by cost due to at-risk aggressive behavior of dominant males.”

The final word

So is there any evidence to support the rumors that ginger cats are more likely to be friendly as well as zany? The answer is yes, but it’s weak and limited, with some conflicting findings. The data we have is also from primarily self-reported owner surveys, rather than direct links to studies about aggressive events or specific behaviors. Better quality data from larger studies may shed light on the picture.

Until then, all we can do in this household is enjoy when Ernie is feeling in a chill and cuddly mode, and get the spray bottle ready when he’s literally climbing up the walls!

And now, let's talk about the known connections between hair color and behavior. A number of years ago, several studies investigated the anecdotal phenomenon that anesthesiologists reported of red-haired people being more challenging to anesthetize, typically requiring a greater dose of anesthetic. It turns out to be true. See Liem et. al. Anesthesiology, V 101, No 2, Aug 2004. (I can send you a reprint). This is also seen in rodents (Xing et. al., Anesthesiology, V 101, No 2, Aug 2004). Back when I taught 1st year veterinary students, we discussed this phenomenon. It relates to the primary determinant point of coat color, the Melanocortin 1 receptor (MCR1 - which is not X-linked). This is a classic example of neuro-endocrine interactions, and the efficient use of genes, where one gene may have multiple jobs to do. The ligand for MCR1 is alpha-MSH, which is derived from Pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), whose other products include ACTH and Beta-endorphins. So really, it should not come as a surprise that coat color (or hair color in humans) might actually be linked to behavior!

Well we had two ginger cats often come by our place. Both males. There was Simon who loved to be sung to and the august and very dignified Mr. Beebers, a large male, who resented being laughed at and would turn his back and sit ignoring you if you made light of him. Both cats were pretty wonderful and fully "people" in a sense.