“When you hear hoofbeats behind you, don't expect to see a zebra.”

— Theodore Woodward, MD

“Yes, common things are common, but in emergency medicine, we have to think worst first.”

— Jeff Jarvis, MD

Hunting Zebras

One morning about a decade ago, I was walking down the hospital hallway when I was stopped dead in my tracks by a vet student wheeling a Great Dane outside on a gurney for its walk. Buddy was lying on his side, panting heavily. A sickly shade of purple colored his puffy thigh. Buddy felt hot, his rectal temperature read 104.1F. I felt for femoral pulses: they were thready, and weak.

Hmm…

I gently touched the bruised area and Buddy howled in excruciating pain. He sounded like an animal who caught his foot in a bear trap. The swelling looked pretty bad, but this reaction was massively disproportionate.

“Who’s the clinician on this case?” I asked the student.

“Dr. Tanner1” he replied.

“Did she look at this patient this morning?”

“I…I think so?”

“Did you actually see her evaluate Buddy?”

“…”

His eyes darted away, clearly uncomfortable.

It was obvious no doctor had examined this dog because it would be impossible to miss his bruised leg on even the most cursory exam. And now the student was awkwardly trapped in the middle between services and didn’t want to get anyone in trouble.

“Can you page Dr. Tanner? I need to talk to her. Right NOW.”

I briskly walked towards her office. We had only a few hours to save this dog’s life.

Buddy almost certainly had necrotizing fasciitis, also known as infection with flesh-eating bacteria.2

Bullshit.

She didn’t say the word out loud, her face did.

“Really? Necrotizing fasciitis?? That’s so rare. I’ve never personally seen a case of NF, have you?”

“Yeah, actually. There was a horrible one during my internship, it really stuck with me.”

I explained how everything with Buddy fit, from the bruising and edema, to the disproportionate pain response, to signs of shock.

She was still skeptical.

Dr. Tanner: “Why couldn’t this just be cellulitis? When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.”

“Have you put an ultrasound probe on his leg?” I asked.

She hadn’t, but agreed it was reasonable. We also marked the top line of the swollen and discolored area to watch for spread.

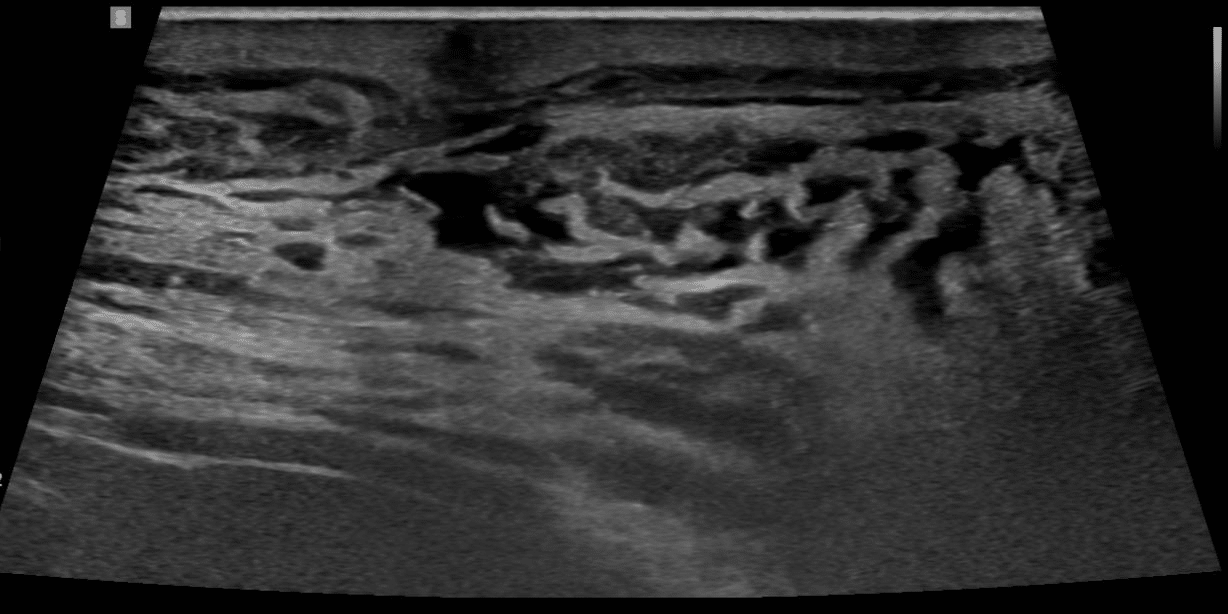

As the radiology resident fanned the ultrasound probe around, the image on the screen was riddled with black pockets of fluid zig-zagging through the connective tissue and fat under Buddy’s skin. They gently stuck a needle into one of the larger accumulations and sucked up the liquid into a syringe. It was straw-colored but contained floating chunks of material. They sent a tube of the sample down the hall for me to look at under the microscope.

The slide was riddled with melting white blood cells and cocci bacteria. Specifically, cocci arranged in chains. Like Streptococcus. And if that wasn’t enough, Buddy’s leg was turning from purple to black, and dark little fingers of bruising were creeping above the line we marked. This clinched the diagnosis for me.

Tanner was still not sold. She was looking at Buddy’s bloodwork and coming up with a half-dozen theories for each abnormality.

“His white count is low and he’s anemic. Maybe he’s got cancer hiding in his bone marrow? That could make him immunocompromised and lead to an infection.”

“Oh, come on—this is NF, it has to be! What more evidence do you NEED?!”

“The burden of proof is high. You know what that diagnosis means: we’d have to remove Buddy’s leg.”

This was true, the main treatment for NF is prompt and aggressive surgery to remove all affected parts of the body before it spreads.

“I don’t know if their owner is OK with amputation. Let’s do a bone marrow biopsy first and see what it looks like.”

Of course, the person who would have to collect that sample was me. I didn’t think that was appropriate, ethically or medically, but hospital policy forced me to do the procedure anyway.

A few hours after collecting the bone marrow, Buddy arrested. We couldn’t get him back with CPR. He most likely developed multiorgan failure secondary to sepsis.

When we looked at the bone marrow sample that evening it was non-diagnostic.

Flesh Eating Disease

In fairness to those clinicians, necrotizing fasciitis (NF) is uncommon to rare in veterinary medicine. I never had a lecture on it in vet school. There is no entry for NF in the Merck Veterinary Manual. Even the research literature is sparse: The largest study I could find is a 2022 retrospective case series of 23 dogs3. My main exposure was through several patients I saw as a vet student and intern.

Necrotizing fasciitis earns its grim nickname based on its ability to spread through soft tissues at an alarming rate, often advancing several centimeters per hour. It begins when bacteria proliferate and release powerful toxins that damage tissue and cut off circulation by blocking blood vessels. In dogs, the most common culprit is β-hemolytic Streptococcus canis, though other organisms including Staphylococcus species, E. coli, and Pseudomonas can also cause the condition. What makes NF particularly insidious is that it can develop without an obvious source of infection—while some cases follow surgery or traumatic injury, others arise seemingly out of nowhere, making early recognition challenging.

The telltale sign is pain that seems wildly out of proportion to the visible lesions—a dog may howl in agony when a seemingly minor bruised area is barely touched. This extreme pain response, combined with rapid progression of swelling and skin discoloration, should immediately raise suspicion for the disease. Imaging can provide additional clues: radiographs may show characteristic "soft tissue wisps" in the subcutaneous space, while ultrasound reveals thickened fascial planes and fluid accumulation. However, waiting for definitive test results is a luxury that necrotizing fasciitis patients don't have, as we tragically saw with Buddy.

Medical management alone almost never succeeds. The infected and necrotic tissue must be removed. Without aggressive surgery, the mortality rate approaches 100%. As a 2023 case series and literature review in Today’s Veterinary Practice puts it:

The most recent and extensive veterinary study suggests a survivability rate of 80% to 90% for dogs that receive a combination of surgery, antibiotic therapy, and supportive care. The stark contrast in mortality rate with and without surgical intervention is compelling evidence for immediate surgical intervention. Various surgical procedures, including debridement, drain placement, and negative pressure wound therapy, have been described with successful outcomes. In humans, mortality increased by 9.4-fold when surgery was delayed for more than 24 hours. Delay between presentation and surgical intervention is extended by awaiting biopsy results, cytology results, or cultures before performing surgery.

Seeing Double

Several years later, one of the residents came up to me to ask about her own dog, Lola. Dr. Harper adopted Lola during her time in vet school in the Caribbean. Like pretty much all island dogs, she had heartworm and Ehrlichia, but those were easily treated.

What was more troublesome was Lola’s chronic diarrhea from Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). This required steroids to tamp down her body’s autoimmune response, just like people with ulcerative colitis. Of course, this caused a lot of side effects, like making her drink a lot more and pee all over the house.

None of that bothered Dr. Harper today. What did was a recent trip to the dog park. Lola was running to catch a frisbee and tripped over a rock. There wasn’t any external wound visible, but she developed a bit of a limp in her back left leg.

The weird thing is Lola was way too sore for just an orthopedic injury. She started guarding her ankle and would cry when Harper tried to inspect it. Her hock was starting to bruise, which definitely didn’t fit with a minor muscle sprain or partial ligament tear.

When I went to the ward to take a look at Lola with Dr. Harper and saw the lesion my stomach got queasy.

This felt like Buddy all over again.

We talked about that case and decided we needed to be aggressive. We marked the line on her leg where the swelling stopped and checked on it hourly.

It kept spreading.

Dr. Harper asked her faculty members about the possibility of necrotizing fasciitis. They were incredulous, and wanted to run more tests, so we popped a probe on the hock, and wouldn’t you know it: fluid pockets.

We sampled the gross liquid and did a quick cytology: chains of cocci.

Dr. Harper didn’t want to take a chance.

“Let’s take her to surgery.”

During the operation, the surgeons found the inside of Lola’s leg was filled with gray, fragile tissue that looked like rotten deli meat. They agreed she had necrotizing fasciitis, and we had caught it in time. The steroids may have increased her risk of NF, but there was no way to know for sure. It could have been just bad luck.

A few hours later, Lola was groggily waking up from anesthesia. She kept looking back at the shaved stump over her left hip in confusion. It took a few days for her to adjust to her new three-legged reality. But she was back to running on the beach in no time, and enjoyed many more years of life.

Buddy and Lola’s cases are inextricably linked in my mind. Two patients with the same disease in the same hospital, just a few years apart. One died due to hesitation in the face of a relentless pathogen that doesn’t give us time to hem and haw. The other lived due to bold action. I’m reminded of the lyrics to the song “Freewill” by Rush:

If you choose not to decide,

You still have made a choice

These two patients also show how important mutual respect and trust is between care teams. Dr. Tanner and I had a relationship that could be characterized as frosty (at best), while Dr. Harper was a friend. The diagnosis I provided to both of them was the same, but only one was willing to listen.

Finally, these two mirror image examples of necrotizing fasciitis show how generally good medical advice like trying not to diagnose rare or unlikely diseases cannot be applied universally to every case. Some diseases are tougher to spot than others, and you can’t find what you aren’t looking for.

Names and identifying details of patients and clinicians have been changed in this case

If you want to see what “flesh eating bacteria” lesions looks like, you can follow this link [TRIGGER WARNING: It’s gross]: Google image search veterinary medicine necrotizing fasciitis

Quilling LL, Outerbridge CA, White SD, Affolter VK. Retrospective case series: Necrotising fasciitis in 23 dogs. Vet Dermatol. 2022 Dec;33(6):534-544.

Good stuff Eric. I've never before seen an ultrasound image of necrotizing fasciitis. Poor dog. And how in the world was a bone marrow aspirate indicated?!

Another really good piece, Dr. Fish. I felt like I was literally IN this with you, that’s how real and compellingly written this is.

I’m so glad you were able to make a difference for Lola and give her many more years with her mom, Dr. Harper.

And I particularly enjoyed the reference to Rush’s “Freewill.” Great line from that song, one of my all-time favorites. Good old Geddy Lee’s high falsetto singing away…