Five-Minute Paper: Mutant FIP Outbreak

How a recombinant canine/feline coronavirus caused a deadly outbreak in Cyprus

For this edition of “Five-Minute Paper” I will be walking through a study concerning a breaking news story: a deadly outbreak of an unusual mutant coronavirus causing a highly-transmissible variant of Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP). This study was uploaded to bioRxiv as a pre-print ahead of peer reviewed publication in a journal, so the final version may differ from what is discussed here. However, since this is an important and timely story that has been reported in Science and other outlets I thought it was appropriate to cover this preliminary data.

The Study:

Attipa C, Warr AS, Epaminondas D, et al. Emergence and spread of feline infection peritonitis due to a highly pathogenic canine/feline recombinant coronavirus. bioRxiv 2023.11.08.566182

Abstract

Cross-species transmission of coronaviruses (CoVs) poses a serious threat to both animal and human health. Whilst the large RNA genome of CoVs shows relatively low mutation rates, recombination within genera is frequently observed and demonstrated. Companion animals are often overlooked in the transmission cycle of viral diseases; however, the close relationship of feline (FCoV) and canine CoV (CCoV) to human hCoV-229E5, as well as their susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 highlight their importance in potential transmission cycles. Whilst recombination between CCoV and FCoV of a large fragment spanning orf1b to M has been previously described, here we report the emergence of a novel, highly pathogenic FCoV-CCoV recombinant responsible for a rapidly spreading outbreak of feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), originating in Cyprus. The recombination, spanning spike, shows 97% sequence identity to the pantropic canine coronavirus CB/05. Infection is spreading fast and infecting cats of all ages. Development of FIP appears rapid and likely non-reliant on biotype switch. High sequence identity of isolates from cats in different districts of the island is strongly supportive of direct transmission. A deletion and several amino acid changes in spike, particularly the receptor binding domain, compared to other FCoV-2s, indicate changes to receptor binding and likely cell tropism.

What is this study about?

This study documents an FIP outbreak in Cyprus that lead to an estimated 8,000+ cat deaths on the island, and it also investigates the genetic and molecular characteristics of this unique coronavirus strain.

Who did the research?

This was a truly collaborative, international effort between labs and clinics in Cyprus and Greece, the Cypriot Ministry of Agriculture, the Royal (Dick) Veterinary School at the University of Edinburgh, the Royal Veterinary College in the UK, and a laboratory in Germany.

Who paid for it?

This research was supported by two funding agencies: EveryCat Health Foundation award number EC23-OC1 and BBSRC Institute Strategic Programme grant funding to the Roslin Institute, grant numbers BBS/E/D/20241866, 332 BBS/E/D/20002172, and BBS/E/D/20002174. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

What did they do?

This study can essentially be divided into two parts. First, there is an epidemiological study of the outbreak and the clinical/pathological characteristics of this variant of FIP. Second, they sequenced the viral genomes and analyzed their similarity to other feline and canine coronaviruses, followed by predicting what impacts the mutations would have on the coronavirus Spike protein (which the virus uses to enter cells).

What did they find?

Epidemiology

Veterinary records were searched from a laboratory in Cyprus and a few cats in the UK recently imported from Cyprus were also included

Cats had to (1) meet the European Advisory Board on Cat Diseases diagnostic guidelines for FIP and also (2) have a positive feline coronavirus RT-PCR test to be included

A subset of these cases had histopathology and FCoV immunohistochemistry performed (which was consistent with FIP)

165 cases were identified in the first 8 months of 2023, a 40-fold increase from the previous two years

The outbreak was first identified January 2023 in the capital Nicosia

RT-PCR confirmed cases declined in the following months due to publicity efforts increasing awareness and likely leading to vets making presumptive diagnoses without PCR (for financial reasons)

Cases increased in August when the local government allowed human stockpiles of anti-coronavirus medications such as GS-441524, remdesivir and molnupiravir to be used for cats with a positive PCR diagnosis

Clinical characteristics

About 70% of cases were “wet” FIP with effusions, ~28% were central nervous system FIP, and ~2% were “dry” FIP (the hardest to diagnose)

Cases showed NO age discrimination (FIP usually occurs in a “biphasic” pattern, affecting young kittens and geriatric/immunocompromised cats)

Effusions were typical high-protein non-septic exudates

Cases with histopathology contained lesions with multifocal to coalescing, pyogranulomatous to necrotising and lymphoplasmacytic inflammation that was sometimes associated with blood vessels

IHC showed numerous macrophages packed with feline coronavirus antigen

Genetic sequencing and protein structure analysis

RNA samples were collected from 91 FIP cases (2021-2023)

The authors initially performed cDNA/PCR-amplification-based Nanopore sequencing for the Spike protein gene

Virtually all of the cases in the Cyprus outbreak (and one of the UK cases) showed 97% sequence similarity to the hypervirulent pantropic canine coronavirus (pCCoV)

>80% of these Spike gene sequences had a large deletion (630 bp)

Interestingly, this Spike deletion was similar to the ones found in the deadly transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) and the mild porcine respiratory coronavirus (PRCV), both of which impact pigs

The authors dubbed this unique virus FCoV-23

Other genes (Polymerase, Envelope, Membrane, and ORF3c) were sequenced in a subset of cats and these were largely similar to previously documented feline coronaviruses

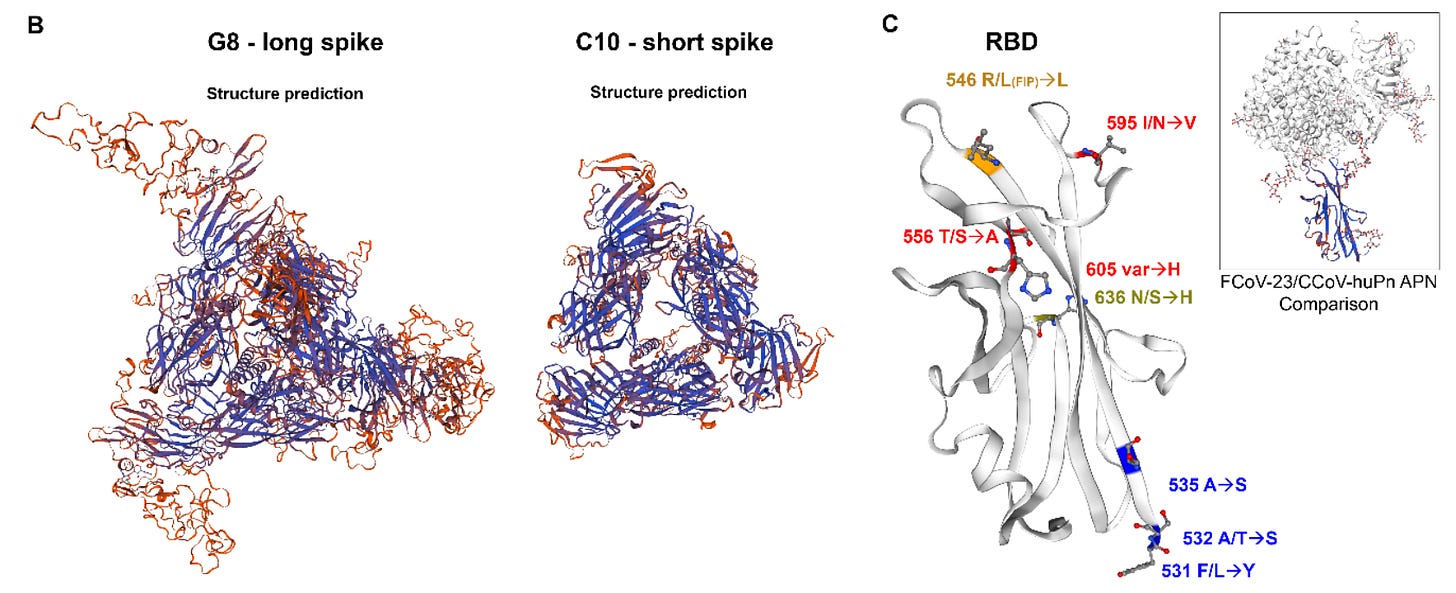

Modeling the mutated protein structure showed the FCoV-23 virus had a more compact and efficient Spike protein structure (C10 below) and numerous amino acid changes in the receptor binding domain (RBD).

What are the take-home messages?

First off, this virus does NOT threaten humans, and is NOT related to COVID-19

This report describes a novel form of feline coronavirus—FCoV-23—that is both highly-transmissible and affects cats of all ages

The authors speculate that Spike protein changes allowed continuous viral shedding that facilitated the mass outbreak (FIP is typically not transmissible)

The outbreak was recognized by an astute clinical pathologist (Dr. Charalampos Attipa) who noticed surging FIP cases in Cyprus and raised the alarm

This highlights the critical importance of practicing clinicians identifying emerging infectious diseases

The virus appears to have originated from recombination of feline and canine coronaviruses, which is not an uncommon phenomenon among animal coronaviruses in nature

SARS-CoV-2 is closely related to a bat coronavirus and may have arisen from similar cross-species jumps

FCoV-23 had some clinical differences in presentation, such as nearly 2x the rate of the central nervous system (CNS) involvement

Some cats were successfully treated with antivirals, highlighting the importance of increased awareness and rapid diagnosis

So far, FCoV-23 seems to be restricted to Cyprus and occasional cases with a travel history. To prevent this local outbreak from becoming a global problem, it is critical that veterinarians stay vigilant and work to prevent viral spread

If this variant of FIP becomes more prevalent, development of effective vaccines and improved access to antivirals will be essential to fight back