From time to time, I get comments or emails from readers (or randos) attacking modern medicine, especially vaccines. Health insurance companies and Big Pharma are frequently the targets of ire, although increasingly people seem to be angry with individual doctors and scientists in the trenches. Distrust of experts is the common theme. Here is a representative example from just this morning:

For starters, the claim that “human kind was healthier before all the shots, meds, and treatments” is easily disproven with a few seconds of Googling life expectancy data:

Average life expectancy is on the rise in the US and broader world. Our pets seem to be living longer, too. In fact, a big part of the rising prevalence of chronic diseases and cancer is because of this success—far fewer of us are dying young, so we now have the chance to develop what some have termed the “Four Horsemen of Aging.”

Are there problems today? Sure. The opioid crisis and COVID-19 pandemic set life expectancy in the US back compared to other developed countries around the world, and this isn’t even getting into stubborn American problems like gun violence, alcoholism, and suicide. Clearly, there is room for improvement!

However, it is only from the relatively comfortable vantage point of 2024 that we have the luxury to forget the horrors of the past. Bubonic plague, aka The Black Death, now known to be caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, wiped out half of Europe’s population in the 14th and 15th centuries. Today it is a serious but survivable illness thanks to antibiotics. Viral scourges like polio, rabies, and smallpox have been nearly eradicated—or at least kept to a low baseline level—by vaccines. For a concrete example, take a look at this data from Massachusetts, which goes back to the early 1800s:

While people can sit back and say these big picture graphs about averages oversimplify, it is much harder to argue with specific examples of medical progress. So I want to take the rest of this article to present several veterinary diseases that have either either been eliminated or defanged by breakthroughs in research.

A Bloody Bad Time

The year is 1978. You are a veterinarian working late on a Friday night again because you have three critically ill dogs in your clinic. Each one of them has explosive, bloody, diarrhea. The smell is unbelievable, fetid and almost metallic.

It’s been like this for months now. The presentation usually goes like this: Young dogs will suddenly stop eating and slow down. Then the vomiting and diarrhea starts. They have high fevers. Their white blood cell counts plummet. Some of the youngest ones have heart problems for some reason. Outbreaks are common in shelters and households with multiple dogs.

You try your best to save them with the limited tools at your disposal: IV fluids and antibiotics. Most of them die anyway.

What the heck is going on???

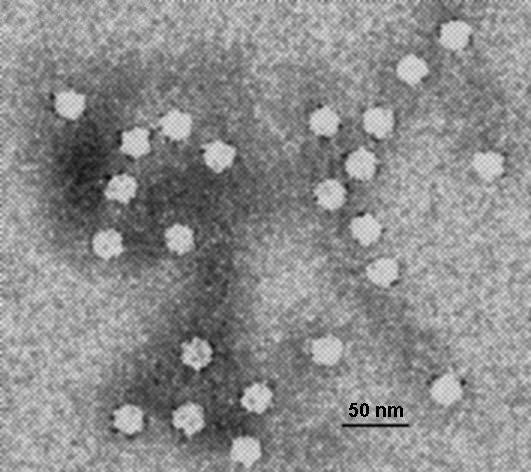

Shortly after the outbreak began, researchers found the answer: a novel pathogen called canine parvovirus (CPV) that likely evolved from several mutations in the closely related feline panleukopenia virus that allowed it to infect dog cells. It began circulating in the late 1970s in Europe, within a few years it was endemic worldwide. CPV is a small, single-stranded DNA virus that spreads through contact with infected feces. The devious little virus particles can survive for months outside a host and are resistant to many household cleaners.

The first vaccine against CPV was developed in 1979, and a more effective modified live vaccine came out in 1980. Soon, the tide of bloody diarrhea and dead puppies began to recede—the vaccines were (and remain) highly effective against CPV. They also reduce the severity of disease for the uncommon breakthrough infections (which are more likely if the correct vaccination schedule is not followed).

Today, parvo vaccines are part of the recommended core immunizations for dogs, along with those for rabies, canine adenovirus, and distemper virus. While veterinarians still have to deal with parvo cases, vaccines have made them much less common than decades ago. And thanks to continuing research, there are accurate bedside tests for parvo to help vets isolate infected patients in the hospital to limit spread, and new treatments like a single-shot monoclonal antibody have joined the fight.

Heartbroken Cats

Fast forward to the late eighties. It’s the era of John Hughes movies, glam rock, and acid wash jeans. I was just a toddler at the time. Dr. Paul Pion was a young veterinary cardiologist on faculty at UC Davis who was researching clotting problems in cats. One day, he saw a patient that changed his life, and veterinary medicine, forever.

It was a white cat named El Blanco. He had thrown a clot to the blood vessels that supply his back legs, and imaging the heart revealed the problem: dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). At the time, this severe form of heart disease, which can also occur in people, killed tens of thousands of cats every year.

When examining El Blanco, Dr. Pion noticed a peculiar eye problem: blindness due to degeneration of the retina. He had been doing some reading on the matter and noticed that scientists had found a nutritional deficiency of the amino acid taurine could cause that eye problem.

Could taurine deficiency also be related to the heart disease?

As he started evaluating more cats with DCM, he found that they all had incredibly low levels of taurine. The UC Davis' team eventually published their groundbreaking report in the journal Science. In brief, they found:

“In this study, low plasma taurine concentrations associated with echocardiographic evidence of myocardial failure were observed in 21 cats fed commercial cat foods and in 2 of 11 cats fed a purified diet containing marginally low concentrations of taurine for 4 years. Oral supplementation of taurine resulted in increased plasma taurine concentrations and was associated with normalization of left ventricular function in both groups of cats.”

In fact, El Blanco was on the cover of that edition of Science, the first for a pet cat 👇

Unfortunately for El Blanco, his heart disease was too advanced, and he passed away from the disease 😔 Other cats drastically improved, and DCM turned out to be reversible with taurine supplementation in many cases. Even better, it was completely preventable by adding enough taurine to cat food! This research was verified in larger studies and triggered new guidelines for minimum taurine levels in pet food that has saved hundreds of thousands, if not millions of cats in the nearly 40 years since this discovery.

The Other Coronavirus Pandemic

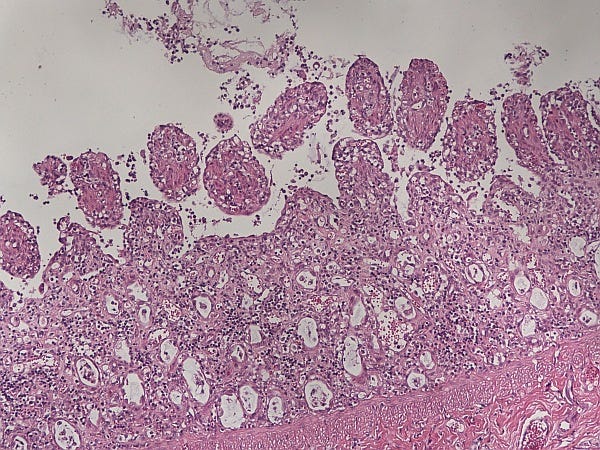

Both the story of parvo and dietary DCM were long before my time as a veterinarian. One disease where I experienced a similar arc from hopeless curse to essentially cured is Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP). When I was in vet school I learned that this horrible disease—caused by a coronavirus distantly related to SARS-CoV-2—killed nearly 100% of cats. It would afflict young kittens and elderly cats. Purebred and immunosuppressed cats were also at risk. Cats with FIP developed severe inflammation in multiple organs, especially the liver, kidneys, brain, and eyes. The telltale sign of the “wet” form of the disease was a build-up of thick, sticky fluid in the abdominal and chest cavities.

As a veterinarian, I had to euthanize many sweet cats with FIP, which always broke my heart. I wanted to figure out how to improve the diagnosis of FIP to prevent cats from developing this death sentence, so I worked with virologists at WesternU and Auburn to study feline coronavirus genes in the blood of shelter cats in Southern California.

A few years later, virologists at UC Davis discovered that several protease inhibitor drugs were having great success treating cats with FIP. In 2019, one of them called GS-441524 was shown to cure 96% of cats with FIP! This was groundbreaking, as nothing had worked against this viral infection since it was discovered in the 1960s. GS-441524 may not roll off the tongue or be a household name, but it is the main metabolite of a drug you probably have heard of: remdesivir, one of the first effective antivirals approved to treat COVID-19. Remdesivir and another COVID drug, molnupiravir, have also show efficacy for FIP, although they are less practical for medical and financial reasons.

Until very recently, GS-441524 was only available through the black market, importing it from drug companies in China. This is obviously less than ideal as it is like buying a street drug of unknown purity. But desperate pet owners and their vets went through these back channels to save cats. In May of this year, the FDA issued a statement saying they would not enforce action against US compounding pharmacies who were selling GS-441524. Now, anyone with a veterinary prescription can get the lifesaving treatment from pharmacies like Stokes.

It is astounding to live through such a revolution a mere decade after graduating vet school. It’s a true testament to the power of science and the dedicated researchers at UC Davis, CSU, Auburn, and other institutions that have been studying feline coronavirus for decades, and it has permanently improved the lives of pet cats everywhere.

It Gets Better

In closing, I want to leave you on this optimistic note: It gets better.

When patients, doctors, and scientists work together, following their curiosity from basic biology questions to clinical trials, we can conquer formerly devastating diseases.

Yes, many illnesses stubbornly resist dramatic cures like the examples above.

Yes, the high costs of medical care are a barrier for many people and animals.

Yes, doctors and scientists get things wrong, and sometimes patients are harmed.

Still, while it is understandable to have nostalgia for a simpler era and and a desire to go back to traditional remedies, we shouldn’t turn our backs on the many marvels of modern medicine. To do so is to return to a time when the lives of people and animals were shorter and filled with more suffering.

Science and technology are the forces helping us triumph over death, after millennia of plagues having the upper hand.

I will never understand why people have such a bad attitude about vaccines and refuse to believe facts and research. So much ignorance exists today.

Delighted to hear about an effective treatment for FIP. My first job out of medical school was in Lafayette, Indiana. I adopted a couple of pregnant stray cats, and soon had a couple litters of kittens. However, within a couple of weeks, they all got sick. Local vet referred me to Purdue vet school. We were a place of interest for several vet students for a few days for the students to see FIP in its various presentations. But, sadly, even they could not reverse the illness at that time, and all felines were euthanized to avoid further misery.