Dear Readers,

In some ways, cancer has been the defining obsession of my life. Professionally, it fascinated me in college and vet school, leading me to specialize in pathology, where a large part of my job is diagnosing malignancy in animals of all kinds. I completed a PhD studying the genetic changes that lead to canine mammary tumors, with the hope that what we learned could help dogs as well as women with breast cancer.

More personally, I lost my aunt Roxanne, who encouraged me to become a writer, to breast cancer. Several of my young classmates and fellow veterinarians have been diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia, colorectal cancer, and ovarian cancer; some are thankfully in remission, while others lost their battles with the disease. And my cat Phoenix required an amputation for an injection-site sarcoma and later died from a rare and aggressive form of lymphoma.

So my curiosity was piqued when I came across several recent stories describing an increasing incidence of colorectal cancer and other tumors in people who are under 50. Today, let’s go over what the data shows about cancer diagnosis trends in young people, what might be driving it, and how this might impact screening recommendations.

—Eric

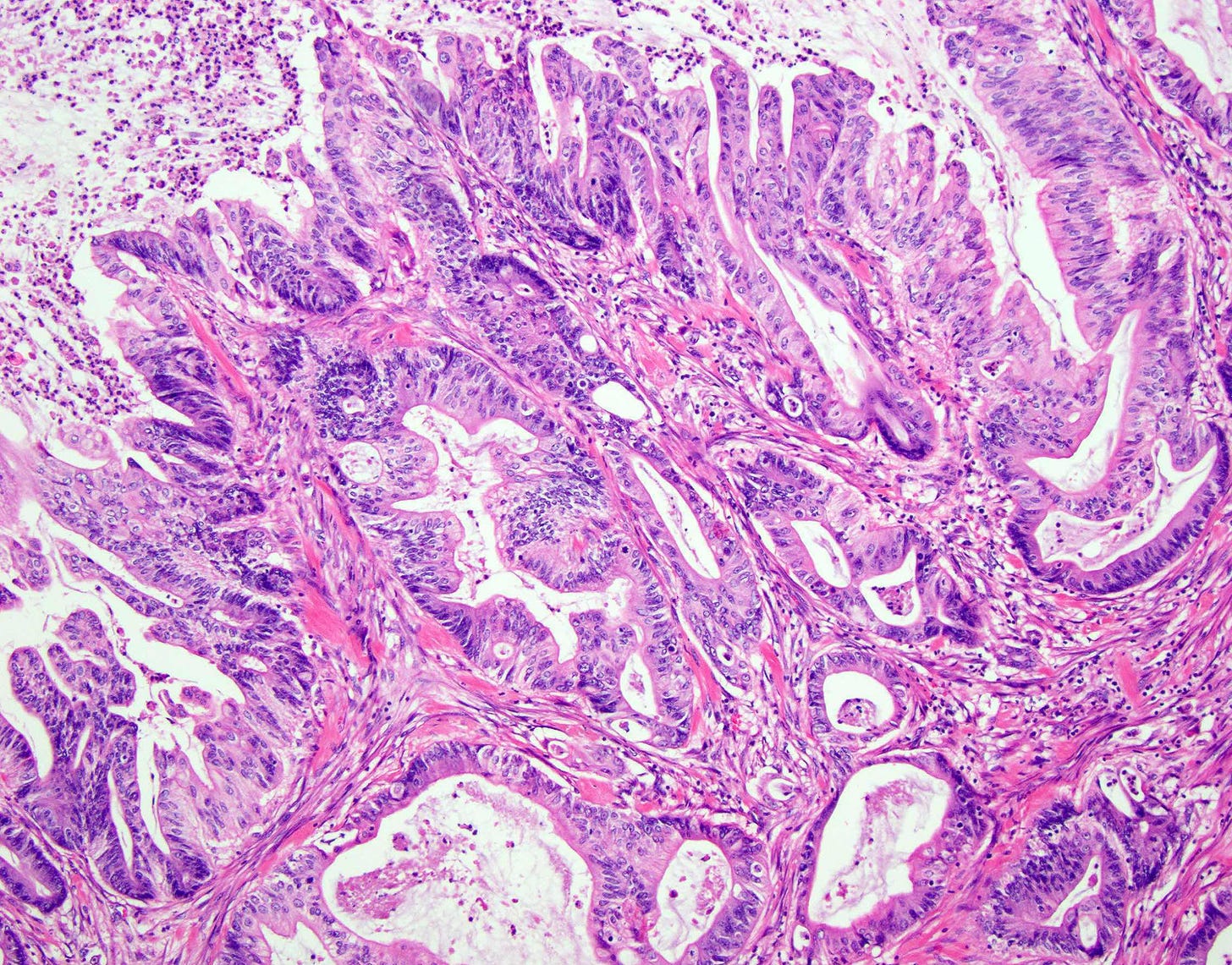

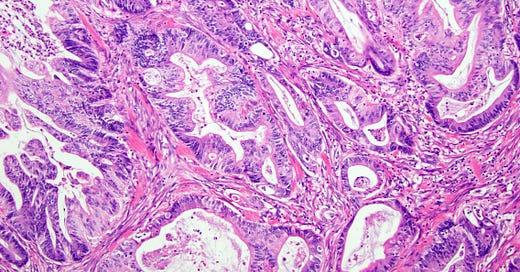

Increasing rates of early onset colorectal cancer

Several news articles over the past few weeks, like this one in the New York Times, have reported that the incidence of colorectal cancer is rising among younger age groups, particularly those in their 20s to 40s, while it's actually declining in older age groups. This increase is mainly seen in rectal cancers and left-sided colon cancers. The reasons for this rise are not entirely clear but may involve a combination of genetic factors, lifestyle choices (like smoking and physical inactivity), dietary habits, and possibly imbalances in gut bacteria. Geographic and racial disparities in cancer rates also suggest complex interactions between hereditary risk factors and environmental exposures. This NPR article goes into more detail about some of the potential culprits:

…researchers are evaluating a range of factors that could be fueling the rise in colon cancer, everything from a lack of vitamin D, the complicated role of the microbiome, to the effect of high red meat consumption and the role of diet overall.

A study published in 2021 found that women who drank more than two sugary drinks per day had more than double the risk of early onset colorectal cancer, compared to women who drank less than one drink. And a study published this month suggests people who eat lots of fresh and minimally processed foods are less likely to develop colon cancer, compared to people who consume lots of ultra-processed foods — including processed meats, sweets, carbonated soft drinks and ready-to-eat meals.

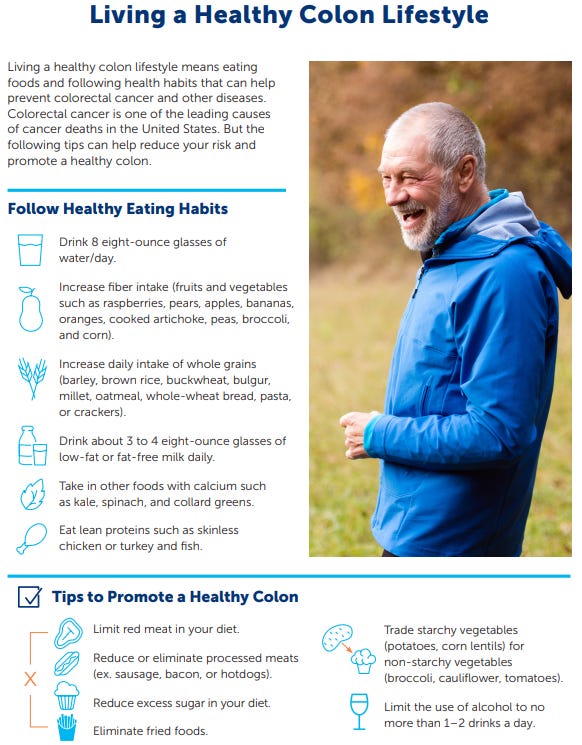

To reduce the risk of colorectal cancer, individuals are advised to follow a healthy lifestyle (see infographic below) and to be aware of symptoms, such as abdominal pain, changes in stool, and rectal bleeding, and to discuss any concerns with a healthcare provider. Screening methods like colonoscopies and tests based on DNA or blood markers are available to detect colorectal cancer or precancerous conditions early, increasing the chances of successful treatment.

All Science Great & Small is a reader-supported guide to veterinary medicine, science, and technology. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you find yourself enjoying these articles and want to receive new ones right in your inbox, consider subscribing 👇

Should we change screening recommendations?

Experts have noticed that early-onset colorectal cancers tend to be more aggressive and are often diagnosed at advanced stages. While routine cancer screenings have been effective in older adults, younger individuals are generally not recommended for such screenings until they reach a certain age. However, due to the rising incidence, screening guidelines have been adjusted, suggesting screenings starting at age 45 instead of 50. Still, this may not be early enough to help those who are developing colon polyps earlier than 45.

, a radiation oncologist who writes the excellent Substack newsletter , has a great piece out about how flawed the current screening recommendations are:Physicians and researchers that deal with colorectal cancer regularly, know that it is 90% preventable. Early detection of polyps via a colonoscopy is the key. We as a collective can change the healthcare system as it pertains to Colorectal Cancer. I believe the 168,000 people who were diagnosed in 2022 and the 58,000 people who died would agree.

Allowing young people between the age of 21-45 the choice to get a screening colonoscopy is the clinically correct thing to do. It is the economically correct thing to do. It is the morally correct thing to do. It is the right thing to do.

Read her whole piece here:

Also included in her article is this video starring Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney talking about the importance of colonoscopies, including filming both of their procedures and the conversations with the doctors. I won’t spoil the ending, but both of them are very glad they got scoped. It is bawdy, hilarious and educational (my ideal blend for learning). Check it out 👇

What about other tumors??

The picture is mixed—we are thankfully making progress against some forms of cancer. For example, cervical cancer rates are plummeting thanks to the extremely effective HPV vaccine, and there may also be benefits for other tumors caused by the virus. Lung, bladder, and laryngeal cancer rates are also thankfully going down (source).

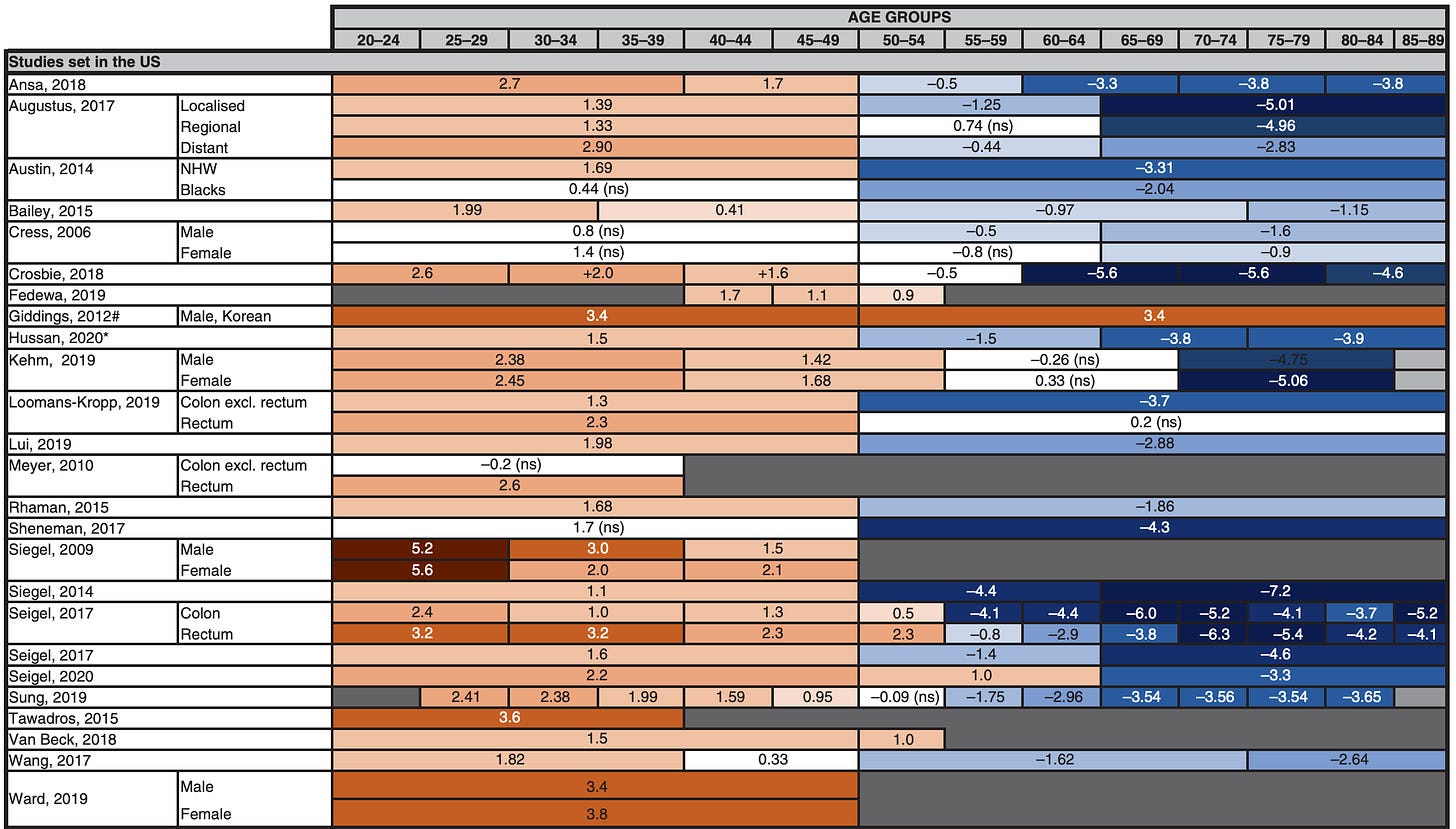

However, over the past twenty years, there has been an increase in the incidence of many types of cancers among people under 50. Besides colorectal cancer, melanoma, lymphoma, breast and thyroid cancers are becoming more prevalent in younger populations. The chart below shows a comparison of numerous studies that looked at incidence of cancer by age group, and orange/red is bad, indicating more people are being diagnosed in that demographic. It paints a consistent picture:

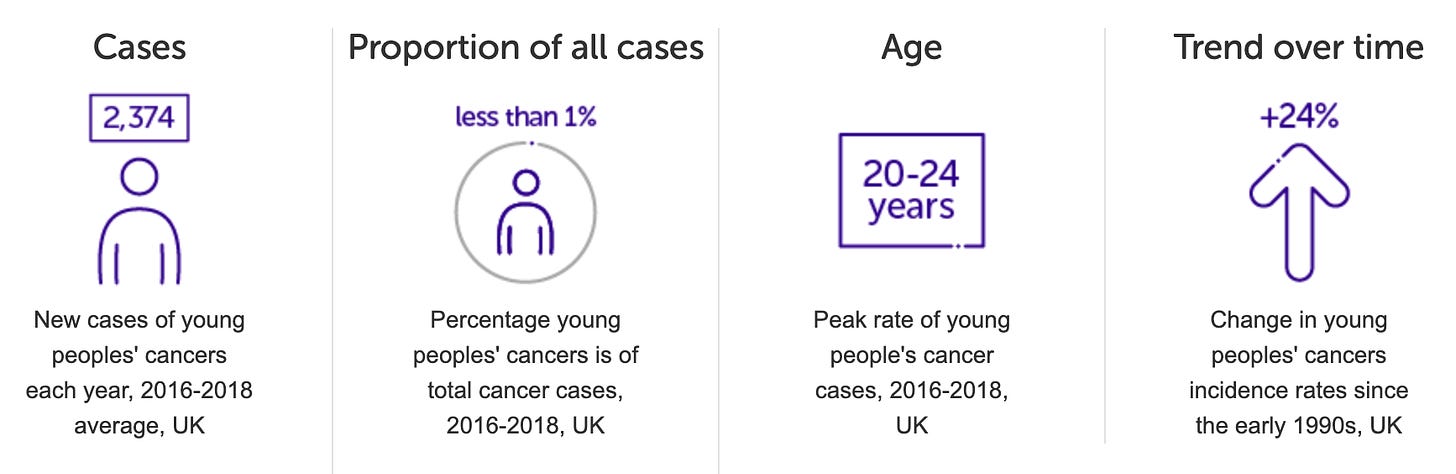

This is not just a problem in America; in the UK, cancer rates for young people are up 24% since the 1990s! Similar trends are seen globally, in both wealthy and developing countries.

Some of this trend is partly attributed to better and earlier detection methods, although as with colon cancer, there is likely a big influence from obesity, diet, and environmental factors.

Fortunately, survival rates for many types of cancer have improved due to advancements in medical treatments, early detection, and personalized medicine approaches. Younger patients often have better outcomes compared to older individuals, partly because they tend to be healthier and more resilient during treatment. However, there remain significant global disparities in cancer survival rates: high-income countries generally have better survival due to advanced healthcare systems and availability of screening and treatment options, while low- and middle-income countries face challenges such as late diagnosis, limited access to treatment, and lack of healthcare infrastructure, which leads to higher mortality.

The role of environmental cancer promoters

Finally, to close out this article, the oncologist and writer Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee recently explored how environmental causes may be driving some of the increase in cancer rates in this excellent piece for the New Yorker. He begins with the history of how we have traditionally tested for carcinogens for the past 50+ years: the Ames test. Named after the biochemist Dr. Bruce Ames who invented it, the eponymous test is ingenious in its simplicity: you exposure bacteria in a petri dish to various chemicals and then look for evidence of DNA mutations, which are the fundamental cause of tumors. While the Ames test is limited in use, it allows a convenient way to screen for substances that may be hazardous.

However, over the years, scientists became aware of a curious problem with the simple model of: chemical → DNA mutations → cancer… Many substances—for example, asbestos—do not cause mutations by the Ames test (or any other more advanced ways of looking for DNA damage), yet still promote cancers like mesothelioma. A classic experiment from the 1940s shed light on one possible cause: INFLAMMATION.

In the experiment, two researchers working at Oxford, Isaac Berenblum and Philippe Shubik, assembled a group of mice, clipped a patch of hair on each rodent’s back, and painted the patches with DMBA, a cancer-linked chemical that was found in coal tar. Yet only one animal in thirty-eight developed a malignant lesion. When the researchers added some slicks of croton oil to the same area, the results were startlingly different. (Croton oil, a blistering, inflammatory liquid extracted from the seeds of an Asian tree, was used as an emetic and as a skin-sloughing exfoliant.) Now malignant tumors bloomed, appearing on more than half the mice. The sequence mattered. Reverse the schedule of application—croton oil first, tar after—and there were no tumors.

It was as though the known carcinogen, DMBA, had primed the cell and the croton oil had catapulted it toward malignancy… But in what sense was croton oil a carcinogen? The mice painted only with croton oil hadn’t developed tumors. It passes a standard Ames test on bacteria, and a more sensitive version of the Ames test that uses fruit-fly cells. It’s negative even with animal cells. There’s no evidence, in short, that it causes DNA mutations.

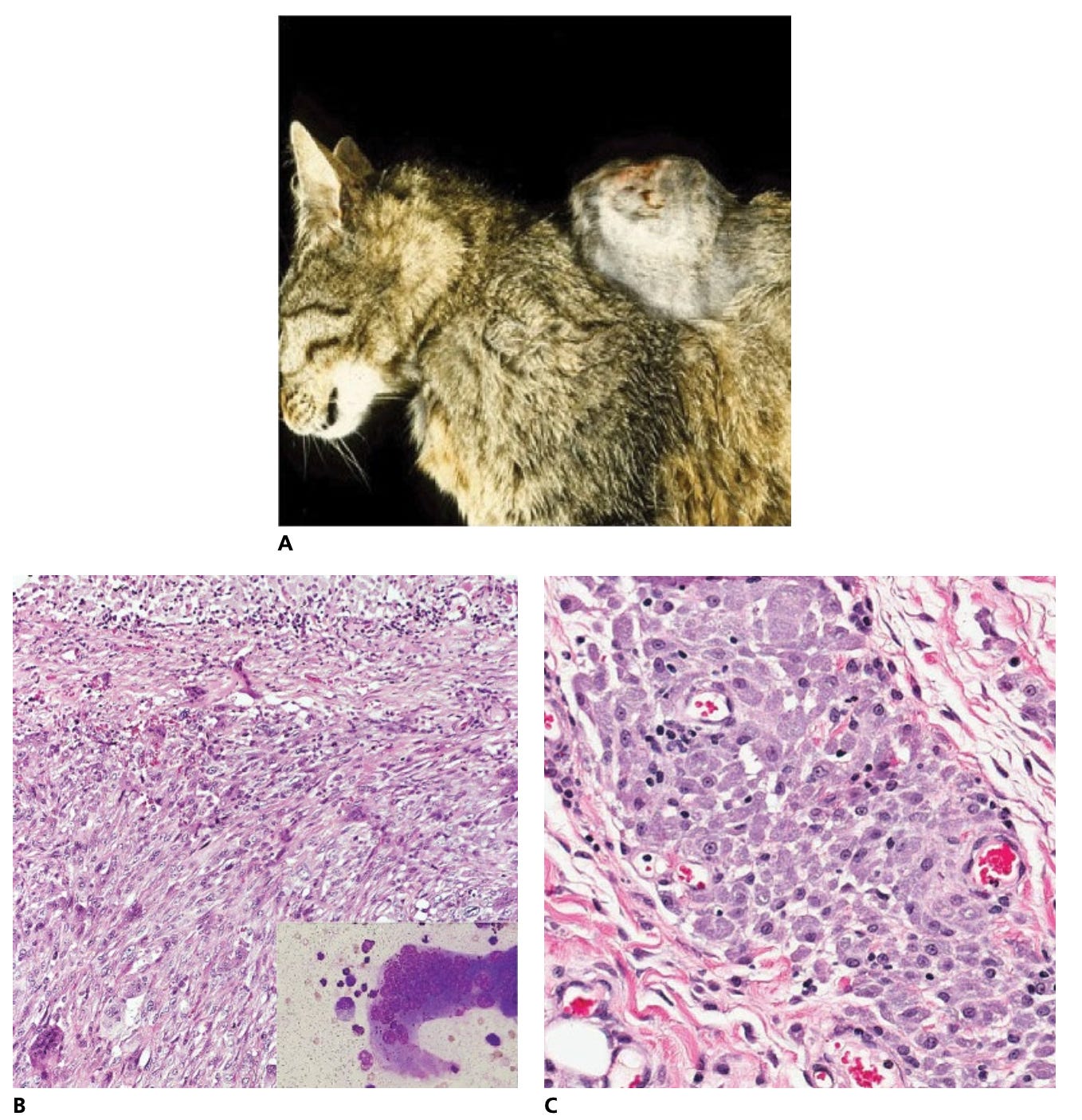

That inflammation can promote cancer is well-established. Veterinarians know this all-too-well from the rare but devastating case of vaccine-associated sarcomas in cats (including my own). The adjuvant in some types of vaccines definitely provokes massive inflammation, but before you go into panic mode about vaccines, it has also been linked to injection of medications, microchips, and even simple sterile fluids. Cats are more pro-inflammatory than other species, but there have been reports of rare tumors associated with foreign body reactions, like a rhabdomyosarcoma associated with a pacemarker in a dog.

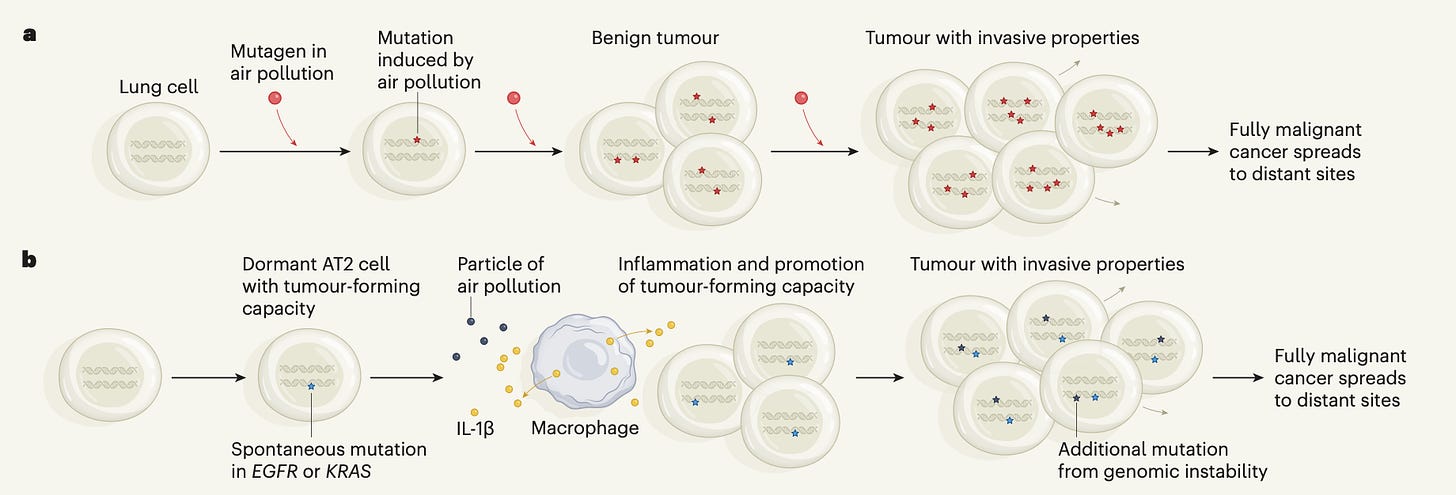

The real question is HOW inflammation does this. Recent research sheds some light on this puzzle. The scientist Charles Swanton and his lab has spent years exploring the links between lung cancer and environmental risk factors, first intrigued by the fact that as many as 10% of patients had no history of smoking. They began to look into air pollution as one culprit, exposing mice to liquid smog (yes, apparently this is a thing you can buy). What they found was that inflammation caused by the smog essentially awakened cells that were already mutated and lying dormant:

“And that’s the answer,” Swanton told me when we spoke later, a jolt of intensity in his voice. “The simplest explanation is that people who don’t smoke, and those who do, have preëxisting mutant cells, albeit at a very rare frequency, in their lungs. In the case of air-pollution-induced cancer, the PM2.5 [EJF: smog] particles activate immune cells to create an inflammatory milieu.” And it’s in this boggy cesspool of soot-spurred inflammation that the mutant cells find their footing.

This figure from the article illustrates the concept:

It is unsettling to think that something as ubiquitous as air pollution could be driving worldwide cancer rates, but that appears to be the case:

The paper in which Swanton’s lab presented its findings about air pollution and lung cancer appeared in Nature earlier this year, and it ends on an ominous note: “Our data suggest a mechanistic and causative link between air pollutants and lung cancer, as previously proposed, and substantiate earlier findings on tumour promotion, providing a public health mandate to restrict particulate emissions in urban areas.” The risk extends to a vast population. “Ninety-nine per cent of the world’s population is exposed to levels of air pollution that exceed the safety guidelines published by the World Health Organization,” Hill told me. Smoking increases your risk of lung cancer far more than air pollution, but the number of people exposed to air pollution is so vast that the over-all toll of each may be similar. Swanton has estimated that air-pollution-induced lung cancer kills seven or eight million people every year.

To connect this concept to the rising rates of colon cancer, it is possible that something in our diets is directly or indirectly provoking chronic inflammation in our gut and promoting formation of polyps and tumors, although we have not identified a smoking gun substance yet. Other cancers may have similar promoters that don’t act as traditional carcinogens, but rather sneaky enablers of the rare mutant cells that already lurk within us.

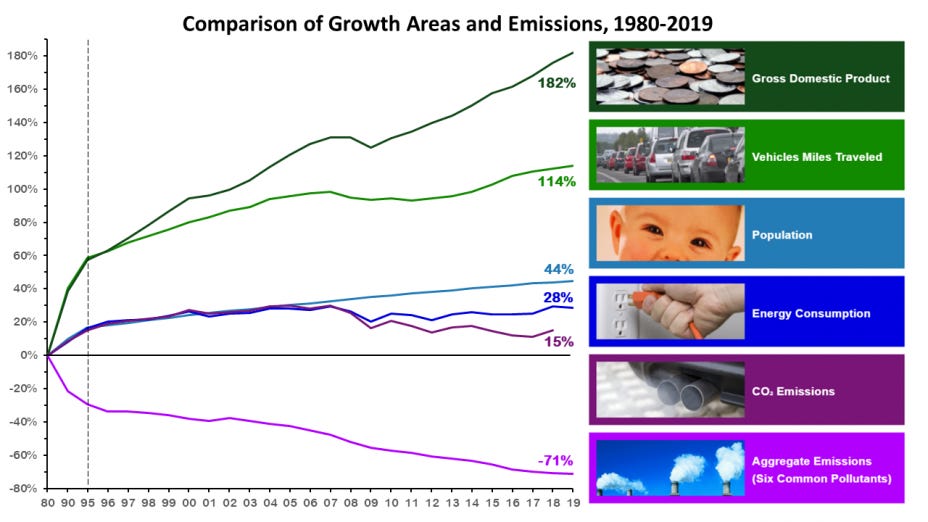

These connections between the environment, animals, and our own health is a perfect example of One Health: we are all linked together inextricably. You cannot separate conservation and green initiatives from societal well-being. While this may seem daunting, progress is possible. After Cleveland’s heavily polluted Cuyahoga River caught on fire in 1969, we formed the Environmental Protection Agency and cleaned up our waterways. Over a span of decades, we drastically decreased lead poisoning in children by reducing lead in fuel, paint, and other household products. Through the Clean Air Act and many other state and federal regulations, we have made great strides reducing air pollution and carbon emissions in the United States:

The first step to solving a problem is admitting we have one. Hopefully through continued research and innovation we can identify the major causes of increasing cancer rates and work to reduce them.

Great article Eric. Thanks for giving us this information. As someone from a family that is extremely cancer prone (sisters, both parents, uncle's, me) it was a must-read. Restacking to Notes!

Thank you for the shoutout, Eric.

How much of this do you think will require a significant overall to our current health care system that was built on diagnosing and treating acute illnesses? There is no incentive (and in fact a financial disincentive) for prevention and early detection. There are also minimal individual incentives for prevention and screening (i.e. no break on health insurance premiums especially in employer and government provided plans).

Tina Marsh-Dillon is doing an excellent series on this in Word to the Whys.