Is VetMed Ready for a "Midlevel Practitioner"?

Letting non-vets diagnose and perform surgery poses risks with questionable benefits

Dear Readers,

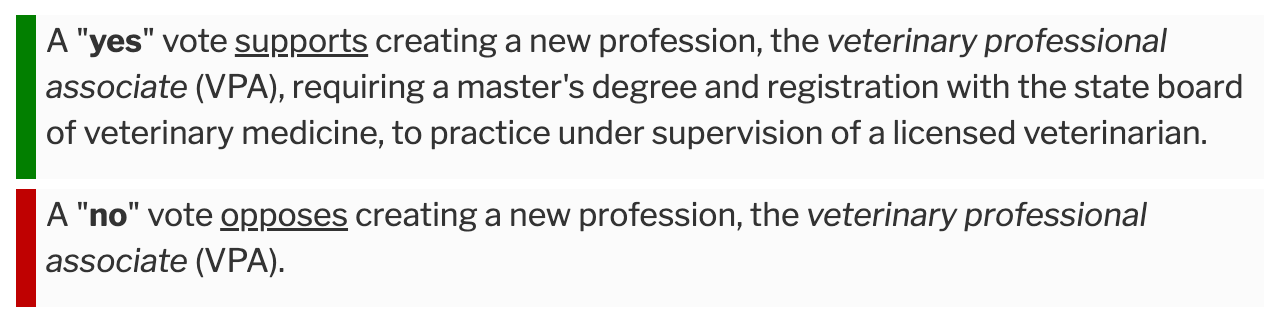

In late August, a petition in Colorado may have changed veterinary medicine forever: Proposed Initiative #145 “Establish Qualifications and Registration for Veterinary Professional Associate (VPA)” gained enough signatures to appear on the ballot this November. PI #145 aims to create a so-called “midlevel practitioner” (MLP) in the mold of human physician’s assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs). A similar bill in Florida, SB 1038, was proposed this year, although it died in committee.

The concept behind this proposal is straightforward: create a new tier of professionals who can take on certain medical tasks traditionally performed by veterinarians, such as surgeries and diagnostic procedures. Proponents argue that this could help alleviate the growing demand for veterinary services, particularly in underserved areas.

While this might sound promising on the surface, we need to critically assess what such a change would mean for animal care, the veterinary workforce, and, ultimately, pet owners. As we dig deeper into this proposal, it becomes clear there are serious risks that might outweigh the benefits. Many veterinary groups oppose this MLP effort.

So do I.

This article explains why by walking through what this bill (and those in other states) aims to create, the possible benefits, and the substantial risks. I hope you find this analysis useful and chime in with your own thoughts in the comments.

—Eric

What is the proposed role and scope of the VPA?

The text of the proposal calls for the Colorado State Board of Veterinary Medicine to recognize a midlevel practitioner who has earned a master’s degree as a VPA. While the bill is written in a lot of “legalese” it would authorize VPA’s to diagnose, prescribe, and perform surgery under the supervision of a veterinarian.

This degree does not currently exist in Colorado (or anywhere else in the US). The Colorado State University (CSU) College of Veterinary Medicine is planning a curriculum to accommodate this new tier of practice. CO Representative and veterinarian Dr. Karen McCormick was quoted in this JAVMA News article about the plans for the CSU VPA degree:

Rep. McCormick, who has seen the proposed curriculum, said the program would consist of three semesters of fully online lecture with no laboratory, a fourth semester of basic clinical skills training, and a short internship.

“How do we assure the public that this person has the proper skill set to perform surgery or prescribe? That they have reached a baseline level of competency and have had enough practice and training to minimize mistakes or miscommunications? None of that is in place or plans to be in place in the near future for this potential position,” she said.

Rep. McCormick added that, given the proposed VPA would operate under a supervising veterinarian, the veterinarian would be liable for all actions of that VPA, including errors made during surgery.

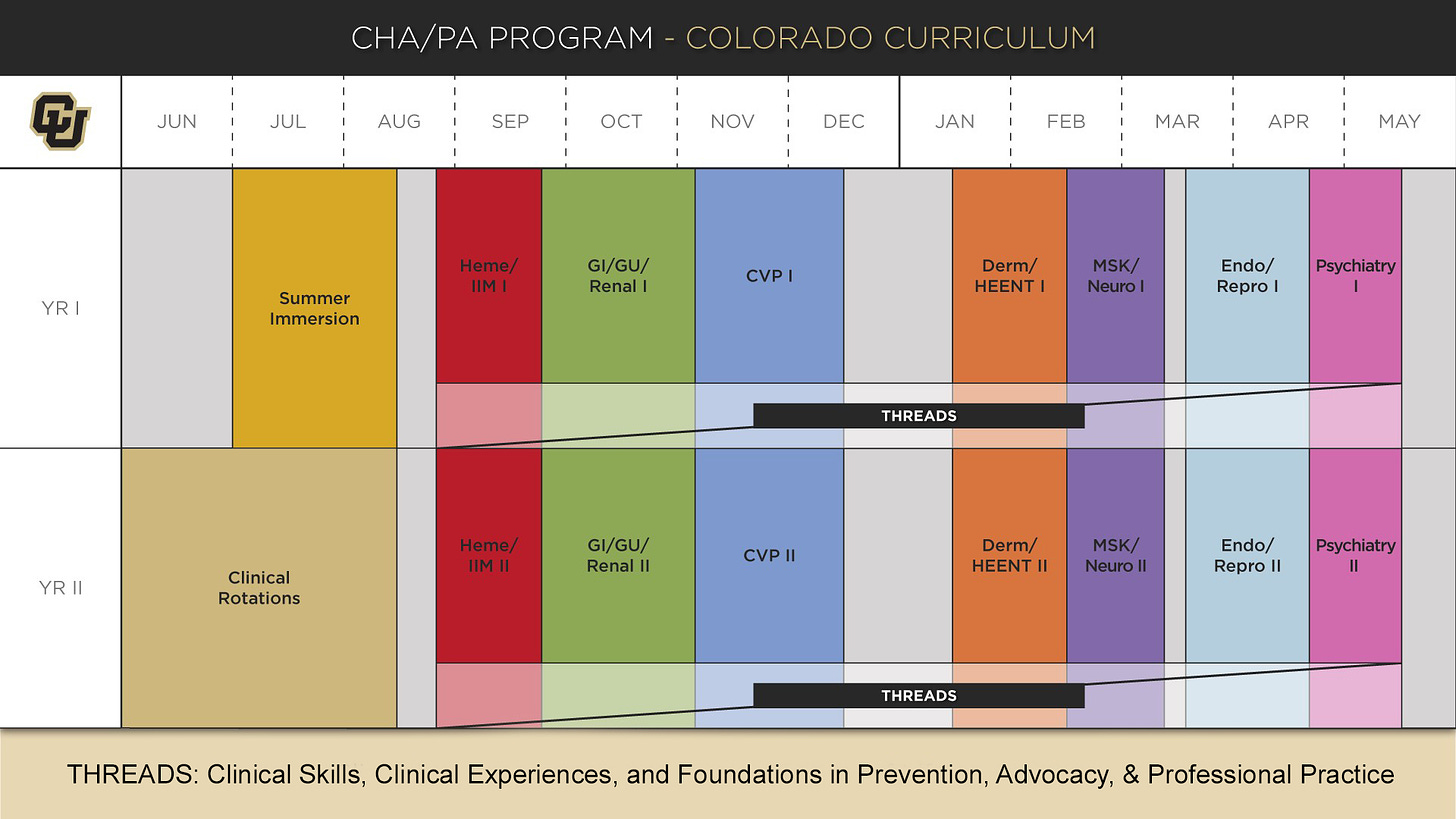

How does this compare to human PA training? Take a look at the University of Colorado at Boulder Physician’s Assistant program:

“The Colorado Curriculum consists of two didactic years, with clinical experiences integrated across both years. The third year of the program consists of 10 one-month rotations. The program begins in July with a summer immersion course that includes fundamentals of learning strategies, PA professional roles, wellness and resilience, and clinical topics.”

I do not have a deep knowledge of whether the CU-PA curriculum is representative of PA programs across the country, but from what little is known about the CSU-VPA degree being developed, the veterinary equivalent is about half as long in length with less classroom and clinical training.

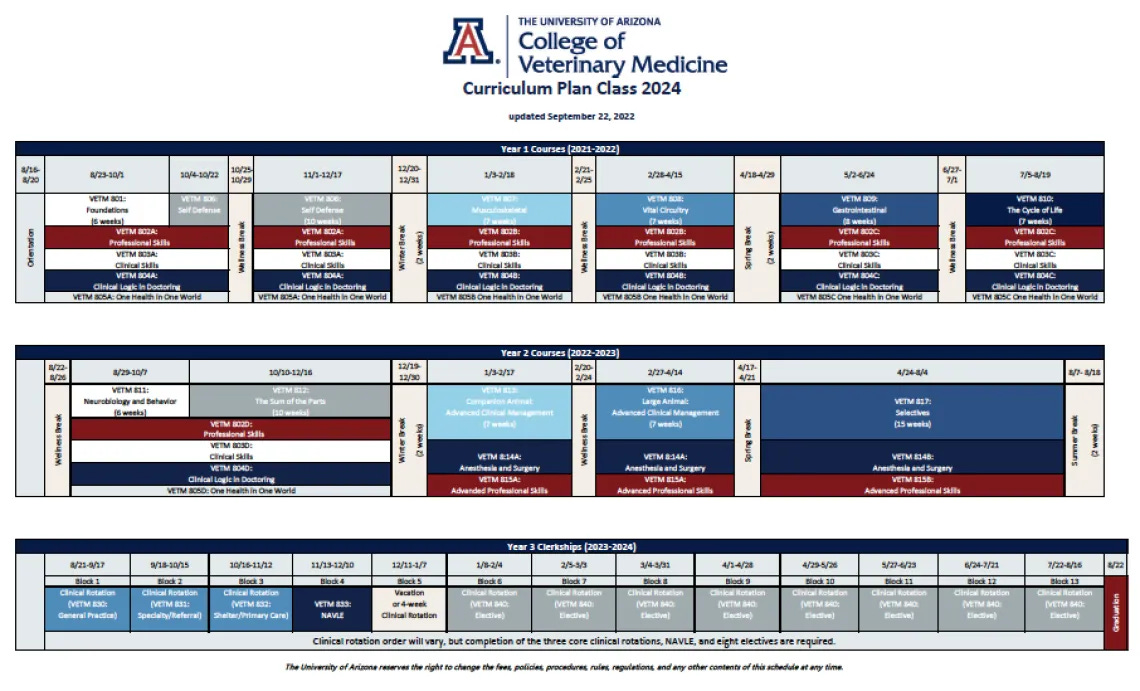

It is worth pointing out that some DVM programs are already three years instead of four. Compare the CU-PA curriculum to the University of Arizona DVM program:

Who supports this bill and why?

CO ballot initiative #145 is supported by a number of non-profit organizations, many affiliated with animal shelters, including All Pets Deserve Vet Care, the Animal Welfare Association of Colorado, the ASPCA, and the Dumb Friends League in Denver. Supporters of the MLP/VPA model make several arguments:

Addressing a Veterinary Labor Crisis

They claim that the veterinary field is experiencing significant workforce shortages that are leading to long wait times for appointments and burnout for vets. Proponents believe that midlevel practitioners could ease the burden on veterinarians, allowing them to focus on more complex cases while MLPs handle routine procedures.

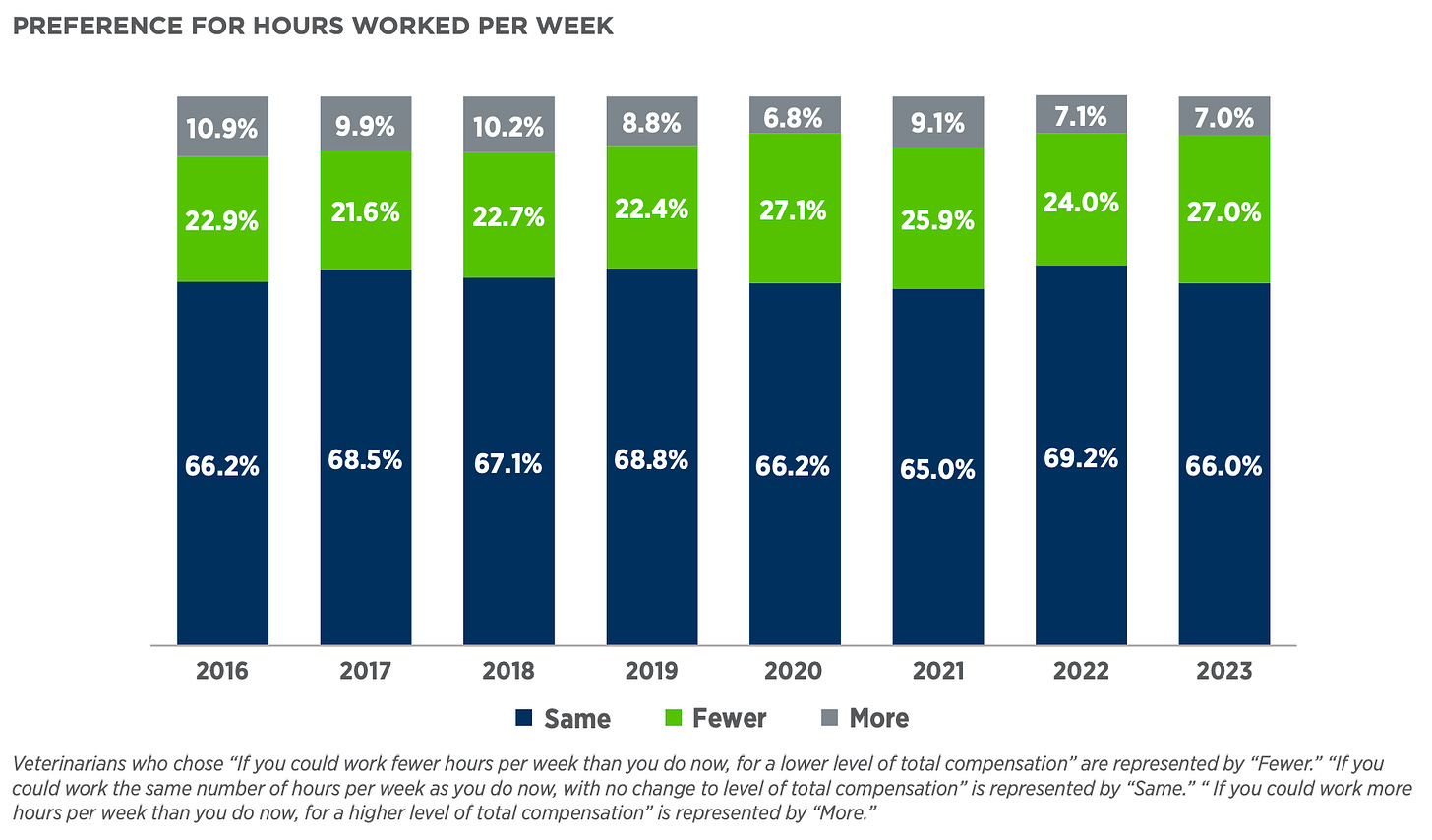

It is worth pointing out that the evidence for the so-called veterinary shortage is quite mixed depending on the source. According to the 2024 AVMA Economic State of the Profession report, 73% of vets prefer to work the same number of hours they currently do (or more). This proportion has been very stable over the past decade, and does not seem to support an epidemic of overworked vets:

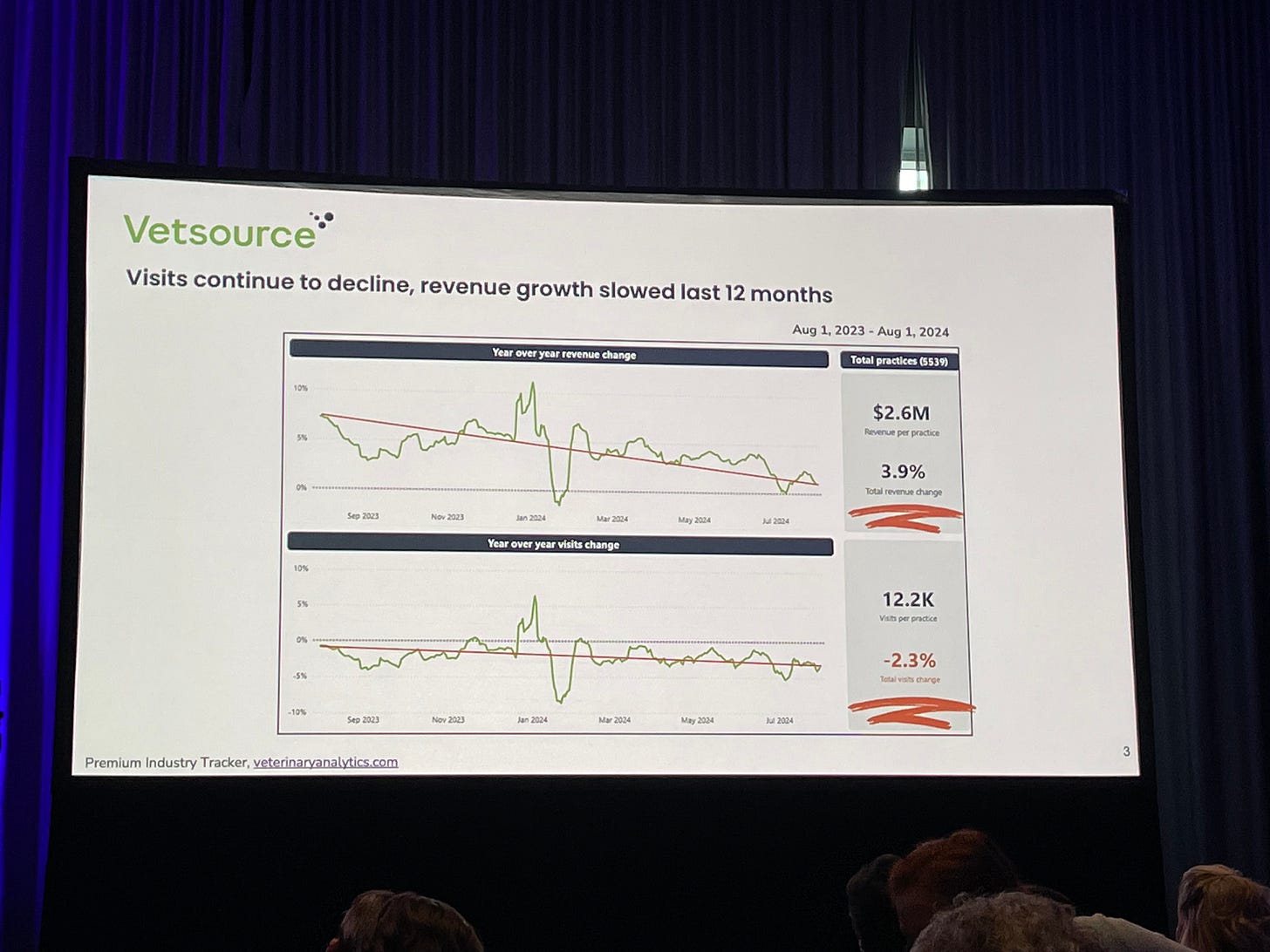

Furthermore, as I showed in my recent post about VIS 2024, recent data shows declining vet visits over the past 18-24 months. It is very possible that the difficulty getting appointments and long waits that plagued 2020-2021 were simply supply shocks created by a (hopefully) once-in-a-lifetime global pandemic:

Improving Access to Care

In rural and underserved regions, access to veterinary services can be limited. The idea is that MLPs could provide much-needed care in these areas, thus helping more animals than the current status quo.

Cost Efficiency

Another argument is that delegating certain tasks to MLPs could lower the cost of veterinary care, making it more affordable for pet owners and reducing the barriers to seeking care.

Will these benefits actually materialize?

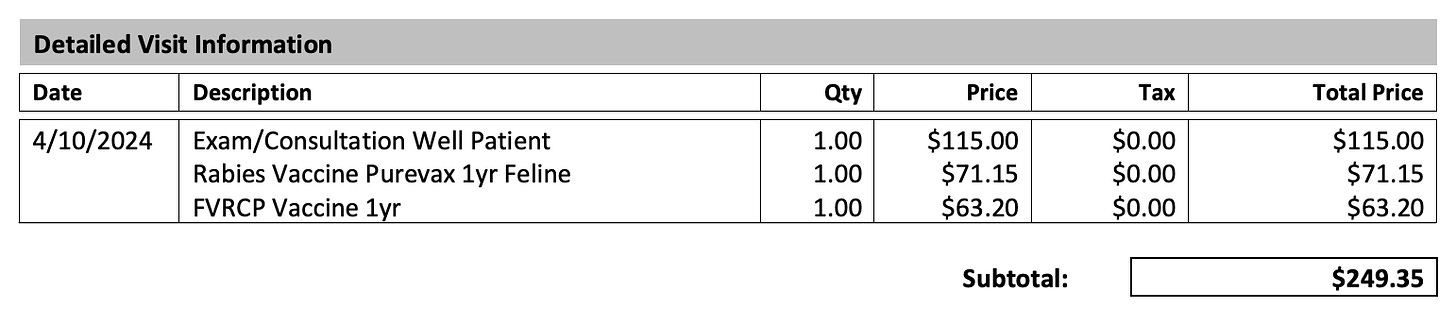

Are these potential benefits realistic? Maybe, but in my view, we should be highly skeptical. I would definitely scoff at the idea that this will lower costs for pet owners. When I took our two cats to the vet for an annual check-up and vaccines this spring, the exam was less than half of the cost of the visit:

For better or worse (I would argue worse), veterinary medicine’s business model has evolved to undercharge for a vet’s time and make up the difference by marking up pharmacy, vaccines, lab tests, etc. Even if you dropped the exam fee by 20-30% that would only make a small dent in the overall bill; is $20-30 once a year really going to influence whether or not someone takes their pet to the vet??

This is setting aside whether or not the practice actually will charge less for VPA visits. My experiences in the veterinary industry suggest they will likely keep the prices the same and simply let the difference boost their bottomline.

As for providing care to underserved areas, I am also doubtful. Over 500 counties in the US are experiencing a shortage of veterinarians, though the needs are for mixed and large (food) animal veterinarians, not primarily those seeing cats and dogs. These shortages persist because of the very low earning potential and preference of most vet students to work in urban/suburban settings with dogs and cats. This is despite loan repayment programs for rural vets and vet schools giving an admissions advantage to prospective vet students who express an interest in large animal medicine (spoiler alert: Once they get admitted, the vast majority suddenly “see the light” and say they want to work as small animal vets after all).

So it seems unlikely to me that VPAs will go into rural practice any more than DVMs already do (especially given the likely worse debt-to-income ratio, discussed below). Finally, it seems self-evident that for a position that requires veterinary supervision, you aren’t going to make a dent if those areas already lack DVMs in the first place!

Who opposes this bill and what are their arguments?

The list of those who are against this proposal is a veritable Who’s Who of veterinary medical groups, specialty colleges, and allied organizations, including:

American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA)

American Association of Bovine Practitioners (AABP)

American Association of Swine Veterinarians (AASV)

American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP)

American Veterinary Dental College (AVDC)

American College of Veterinary Surgeons (ACVS)

Independent Veterinary Practitioners Association (IVPA)

Veterinary Management Groups (VMG)

The Colorado VMA (CVMA)

Three out of four veterinarians in Colorado (from a CVMA survey)

One of the most controversial portions of the VPA is their ability to do surgery. While the bill says it must be “under supervision of a veterinarian,” this often means in legal and practical terms that the DVM is simply on the premises, and not necessarily standing alongside the VPA in the middle of the surgery suite. The veterinary surgery specialist organization ACVS has this to say:

“The American College of Veterinary Surgeons (ACVS) strongly opposes these efforts and believes they will result in increased risk to animal health and safety. All surgical procedures, even those considered routine, have inherent risks that can lead to serious complications (e.g., bruising, pain, bleeding) and even patient death if not performed by trained, qualified personnel. Only a licensed primary care veterinarian and for many procedures a board-certified veterinary surgeon has the education and training necessary to safely perform surgeries on animals and address any associated issues that can arise when performing these surgeries”

Even if you support the idea of improving access to care and potentially an MLP, it should give you pause that so many veterinary groups are opposed to this idea. I am particularly struck by the fact that 3 in 4 Colorado vets are against the VPA; you can’t get more than 50% of vets to agree on hardly anything (maybe “I like puppies”).

Human healthcare has PAs, so why is this controversial?

Many of my readers are from human medicine in the US and abroad, including physicians/osteopaths, nurses, and other allied health professionals. PAs and nurse practitioners have been valuable parts of their care team for decades, so to hear a veterinarian claim they do not support VPAs may come across as strange, perhaps even reflexive protectionism. However, there are a number of differences between vetmed and human healthcare that change the equation.

For one, in human medicine (at least in the US), there is a chronic shortage of primary care doctors, and many PAs/NPs help fill this shortfall. Over half of physicians are specialists compared to practicing primary care. In contrast, the vast majority of veterinarians are primary care providers: According to the latest AVMA numbers available (2023), out of 82,704 veterinarians in clinical practice, only 16,291 (<20%) were board-certified specialists.

Another difference is that physicians generally have to complete many years of residency training before they can practice, even in a primary care setting. This means there is a longer lag time from med school to practice, and residency slots can be a bottleneck that restricts supply is specific medical fields. Veterinarians are eligible to practice right after graduating with the DVM, so the length of required training is already closer to a PA than a physician.

Despite the difference in training, the scope of practice is generally much larger for veterinarians than physicians. Vets in general practice routinely perform surgery, anesthetize patients, interpret radiographs and cytology, and do it all for multiple species. So we are essentially expected to know and do more while receiving less training. Cutting the amount of training down even further strikes me as a dangerous proposition!

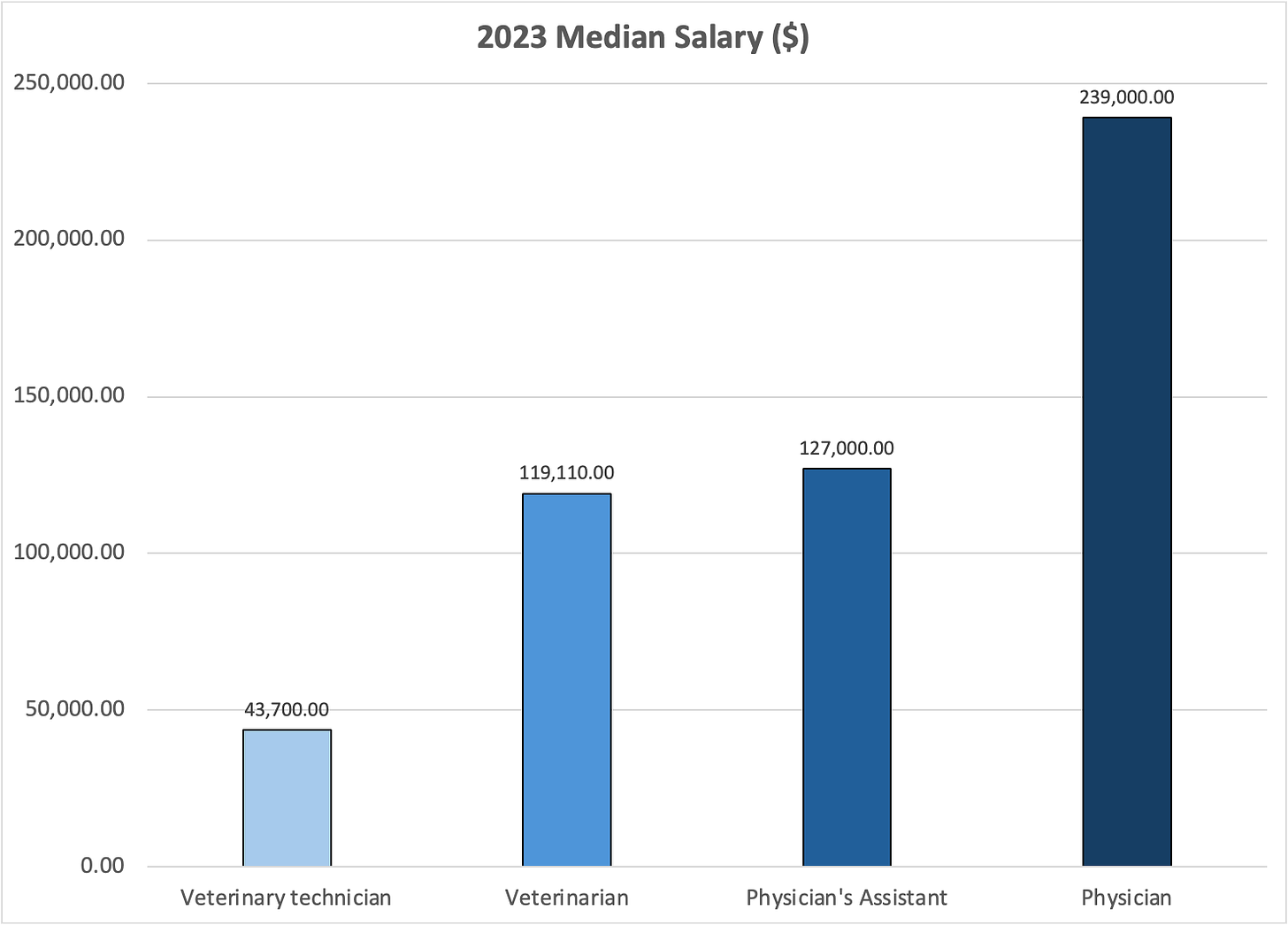

Finally, while my main concern is medical quality, economics do matter. Veterinarians currently earn less than the median salary for a PA in human medicine at $119,000/year, and far less than physicians, while veterinary technicians earn about $44,000:

Presumably, a VPA would earn somewhere between these two ranges, and if you averaged those it would come out to $81,500. This seems likely to both put a ceiling on already underpaid veterinary technician earnings while potentially being a drag on DVM salaries.

Veterinary medicine is already a pretty poor return on investment, with the average student debt in 2023 at $154,451 (and 1/3 have >$200,000 debt, including myself). Given the current tuition for college and professional schools, the cost of a VPA program would almost certainly be at least $40,000 - 50,000/year; is it really economically viable for someone to take on nearly six-figure debt after an undergraduate degree to earn less than double what a veterinary technician does???

A better path forward: Empower our technicians!

Most people in vetmed would agree that we could become more efficient and leverage paraprofessionals better. Rather than creating VPAs out of thin air and trying to jam them into an already economically shaky field, we already have a group of underutilized professionals we could turn to: Veterinary technicians!

I have worked in clinics where vets are still drawing their own blood samples, holding pets for radiographs, and doing manual CBC differentials. Vets often do a lot of the history taking and client interactions that nurses handle in human medicine. This is a waste of both a veterinarian’s time and underutilizing skills of techs that leads them to feel dissatisfied.

Even beyond using veterinary technicians to the fullest of their abilities, there is an entire pathway for specializing called VTS (Veterinary Technician Specialties). VTS certificates recognize techs who go the extra mile for additional experience and training in pretty much anything from anesthesia to critical care, internal medicine, surgery, and more! The process requires documenting case logs, demonstrating specific check-lists of skills, continuing education, letters of reference, and a certifying examination.

The VTS’es I have worked with are amazing and easily rival the MLP that some people claim we need, yet it still preserves the critical role of DVMs for diagnosing, prescribing, and performing surgery. They earn more than non-credentialed techs and enjoy greater job satisfaction by using more of their knowledge and skills. In my opinion, we should build-on this existing pathway rather than cobble together an entirely new part of vetmed from scratch that comes with huge risks and unknowns. Don’t just take my word for it, the Colorado Association for Certified Veterinary Technicians (CACVT) agrees:

“At this time, CACVT does not support the concept of a VPA as proposed in the Increasing Access to Care bill. The strong opposition to the development of a VPA across the industry tells us more work needs to be done to create conditions more conducive to acceptance of this role in the future.

CACVT, however, does support advancing VTSs as mid-level practitioners. VTSs have been recognized for over 20 years with structured knowledge domains and a minimum competency exam for each specialty. VTSs maintain close partnerships with veterinarians and are recognized for their valued role in clinical practice. With direct supervision, interested VTSs could step into a mid-level role to support access to care. This will help provide a career ladder for these motivated individuals.”

What can we do?

Unfortunately, there is not a ton we can do at this point. In the short-term it is up to the voters of Colorado seven weeks from now. If you happen to live in Colorado, I would strongly urge you to vote NO on proposed initiative #145. If you know any CO residents, talk to them about the issue and make sure they are informed about the risks.

As this issue comes up in other states, we can lobby state legislatures to oppose these kinds of bills. A similar proposal died in Florida during committee hearings and negotiations in part due to input from the veterinary industry.

The final stakeholder with a role to play here is veterinary academia—we won’t have VPAs unless schools create those programs and grant degrees. While there may be short-term financial opportunities from adding new tuition revenue streams, I would urge administrators to do some real soul searching about whether or not they truly think this is in the best interest of animals, pet owners, and veterinary medicine. Long-term, if VPAs do become established nationwide, it is incumbent on these schools to create the most rigorous curricula and standards possible. A few online semesters and a couple quick skills labs are simply not adequate.

Update (9/22/24)

There have been a number of new developments in this fast moving story. You can check out my follow-up piece here that looks into the PAC funding for this ballot initiative and a response from one of the bill sponsors:

I am so mad about the CO initiative. It is a way to undercut both vets and techs. Vets need to utilize techs better.

We would be greatly aided in this if techs could get their own malpractice insurance.

Open Meetings: Discussions for understanding Proposition 129: Initiative to Establish Veterinary Professional Associates

Locations and Dates (one or two more to follow)

Tuesday OCTOBER 1, 7:00 - 8:00 PM Niwot Grange. 195 2nd Ave. Niwot, Colorado 80544

Tuesday OCTOBER 8, 6:00 - 7:00 PM Boulder County Main Library, Boulder Creek Room. 1001 Arapahoe Ave, Boulder, CO 80302

Free event, but please register at tinyurl.com/rsvpprop129 to ensure space has not filled.

Event Description:

This is an educational event. The discussion is non-partisan and the event is free. We only need RSVPs to ensure that we have sufficient space and contact information to notify participants if the event space overfills. Description follows.

Jennifer Bolser, DVM, a Colorado veterinarian with 20 years of experience in shelter medicine and small animal general practice, will facilitate a discussion of Proposition 129. Prop 129 is an unusual initiative to create a Veterinary Professional Associate (VPA).

Colorado voters know so little about this initiative!

This lesser-trained veterinary professional would legally be allowed to perform all the responsibilities of a licensed veterinarian, including surgery. We will discuss the initiative, its purpose, what people expect of it, and its likely results. The proposal will impact animals, pet owners, Colorado’s veterinarians, veterinary technicians, clinics, and practices. We’ll work to allow plenty of time to voice questions and concerns.