Known Unknowns: The "End" of The Pandemic?

Reflections on COVID-19 after the W.H.O. declares an end to the emergency phase

“Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don't know we don't know. And if one looks throughout the history of our country and other free countries, it is the latter category that tends to be the difficult ones.” — Donald Rumsfeld, on the failure to find weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) in Iraq; February 12th, 2002

My early memories of The Pandemic—we now frequently refer to it as a distinct entity that needs no further reference as to which pathogen or when—are fragmented dates and images.

January 12th, 2020: Watching Chinese men in white hazmat suits on TV as I walk into the lobby of the Hilton Garden Inn in Portland, Maine for onboarding my new job at IDEXX after leaving the start-up I founded with friends. Thinking to myself, “Hope that doesn’t spread to the US…”

March 27th, 2020: Hillsborough County, Florida enacts a 24/7 “safer-at-home” order with a mandatory curfew. Businesses are shuttered. We have a pantry full of rice, beans, protein bars, and water in case this lasts for another few weeks. My company begins discussing plunging caseload and revenues and the possibility of layoffs.

October 17th, 2020: Sweating on the couch with a fever, in and out of consciousness. Despite working from home, rarely leaving the house, and masking whenever in public, I’ve just been diagnosed with covid by PCR. Passing the time binge-watching the entire Harry Potter series. I will be sick for weeks, and grapple with brain fog and depression for months after. This is days before we were set to fly to Buffalo for a family trip, the first of several that would be cancelled by covid.

March 13th, 2021: Watching hundreds of US military personnel with holstered guns checking in cars ahead of me at the Tampa greyhound racetrack parking lot that has been covered in tents to construct a makeshift federal vaccination center. It feels like something I’ve seen in a B-movie about the end of the world. I get judgmental looks from some of the personnel because I look like a young, healthy white guy getting the vaccine early because of a doctor’s note. People worry there won’t be enough vaccine supply to meet demand, and discuss rationing it for the most susceptible.

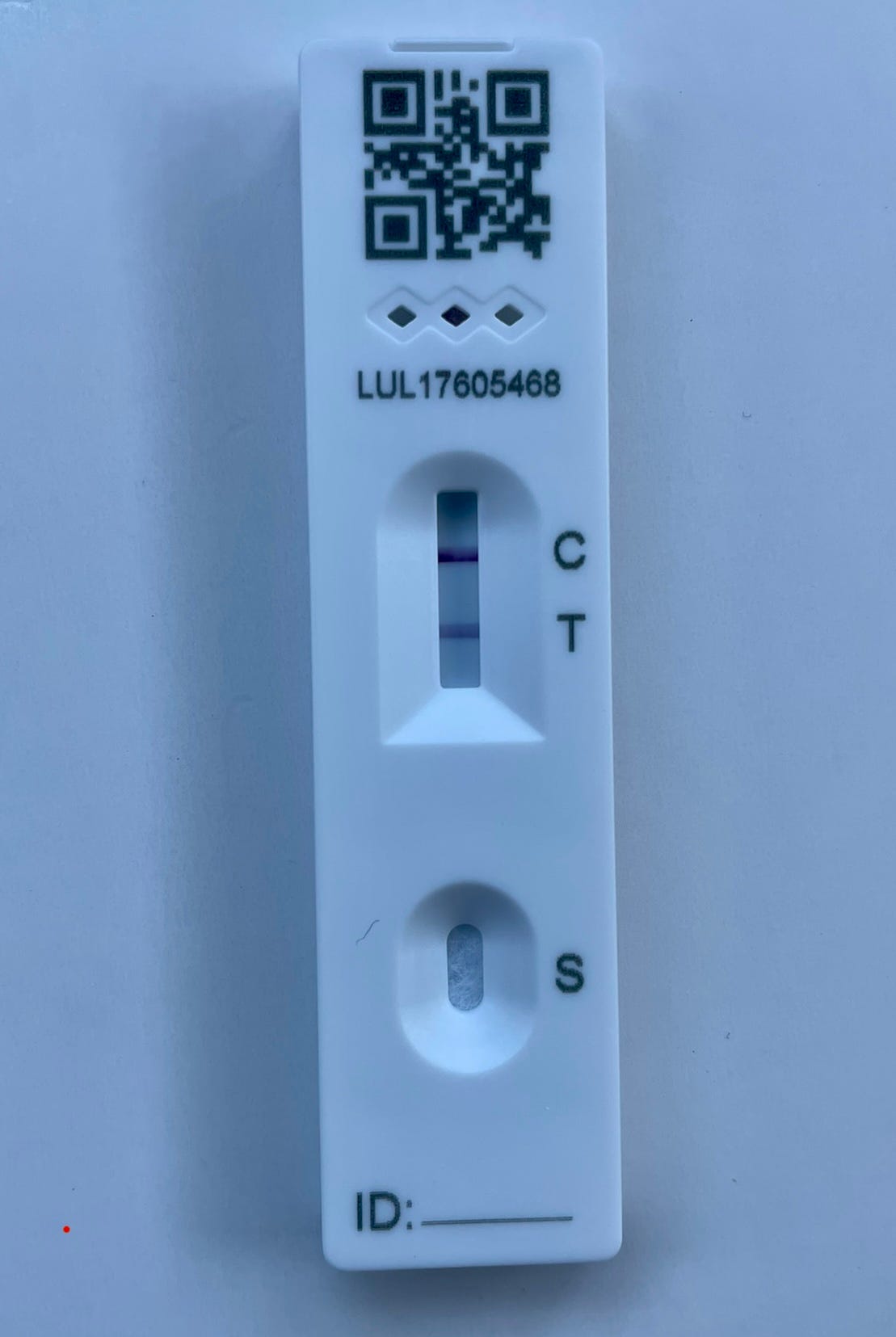

January 11th, 2022: Positive for covid again, this time by rapid antigen test (RAT). I get this test from friends who have kits from family in the UK because they are sold out at every pharmacy here. Lenore and I had just been at the first Disney Marathon weekend since The Pandemic cancelled them. We’d been feeling increasingly emboldened by vaccines and receding case numbers, but the Omicron variant had other plans. She tests negative multiple times and feels fine.

September 7th, 2022: Wearing a mask on a bus to Kampong Gelam in Singapore, one of the countries with the strictest covid restrictions in the world. Able to travel internationally again, things are beginning to feel “normal.” Singapore recently relaxed many social distancing measures, although they leave in place a mask mandate for public transit. Shortly after our trip, the country would retire the remaining precautions.

***

W.H.O. ends global health emergency designation for COVID

All pandemics end, eventually. Last week, the World Health Organization, along with US public health agencies, took the first step towards that conclusion by declaring an end to the “emergency phase” of the covid-19 pandemic. For many people, the pandemic has been “over” for a long time. Some people either never took the virus seriously or abandoned any sense of caution or sacrifice for society in the early months of 2020 (where I live, in Florida, this was the majority of the populace). Others viewed the end as coinciding with widespread vaccinations in 2021. Even more people began to ease up after the Omicron waves caused nearly everyone to become either infected themselves or directly know someone with covid, shattering the illusion that if you were simply careful enough and vaccinated you could avoid the virus forever.

To be clear, The Pandemic is most certainly not over. The novel coronavirus is still mutating and causing illness. This past week there were thousands of covid hospital admissions a day and it’s killing people at the rate of a bad flu year. People with disabilities or compromised immune systems are still under threat and must live more cautiously. What has largely ended is The Pandemic’s salience, the degree to which it upends most peoples’ daily lives and dominates news headlines.

Like many people, you may feel some cognitive dissonance between the statistics I just quoted and the triumphalist headlines that may bring back memories of “Mission Accomplished.” You likely have questions about what, if any, significance the end of the public health emergency declaration has on your daily life. This pair of Substack articles by Your Local Epidemiologist cover how this policy change will impact covid test surveillance:

as well as impacts to health insurance coverage and access to treatments:

***

A One Health approach to coronaviruses

Several months into The Pandemic, doctors seemed “stumped” by the mysterious complications of SARS-COV-2 like rashes, blood clots, cardiac problems, central nervous system involvement, and more. They were likewise perplexed about reinfections that showed the challenge of a durable immune response to coronaviruses. They were also caught flat-footed at how rapidly covid-19 mutated. These soon became known knowns.

As a veterinarian, I was not surprised. While most human coronaviruses before SARS and MERS caused only mild seasonal colds, a wide variety of coronaviruses cause serious disease and often death in animals, ranging from Infectious Bronchitis Virus (IBV) in chickens, to Feline Infectious Peritonitis (FIP) in cats, to multiple different severe coronaviruses in pigs, among many, many other animal species. In fact, I spent several years in vet school and after doing research on feline coronaviruses (FCoV), traveling to multiple shelters collecting blood from feral and rescue cats—where the prevalence of feline coronavirus is high—and running PCR and sequencing on those positive for the virus.

There is a lot we still do not know about FIP. The short story of what we do know is this: a very high percentage of cats are infected with a fairly benign version of FCoV that infects cells of the intestines and causes mild, self-limiting GI signs. In a small proportion of these cats, some combination of viral mutations and maladaptive interactions with the host immune system causes severe, widespread inflammation, particularly involving blood vessels. Until very recently, it was considered 100% fatal. This review article from fall 2020 nicely summarizes the similarities and differences between FIP and covid-19:

Despite the pathogenic differences listed above, the severe acute systemic inflammatory reaction syndrome (SIRS) is common in COVID-19 and in FIP. As above stated, cats may harbour the FCoV without showing clinical signs for years, but when FIP develops the activation of the innate immune response is rapid. The immune response leads to a pro-inflammatory cytokines overproduction responsible of severe clinical and laboratory changes (Kipar & Meli, 2014). A ‘cytokine storm’ similar to that reported in FIP cases has been reported also in patients with COVID-19 (Dhama et al., 2020; Kipar et al., 2006; Pedersen & Ho, 2020; Sarzi-Puttini et al., 2020). In turn, this cytokine storm may induce a multiorgan failure that is responsible for the high mortality rate of critically ill patients with COVID-19. This hypothesis is supported by the promising results of immunotherapies with anti-cytokine drugs, especially when using TNF-α blockers (Russell et al., 2020; Sarzi-Puttini et al., 2020). This type of treatment has never been investigated in cats with FIP, mostly due to cost reasons or to the unavailability of drugs registered for the cat. However, the good clinical response of cats to steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Pedersen, 2014b) supports the hypothesis that suppression of the hyperinflammatory response may temporarily improve the clinical condition. This is not completely curative in FIP, due to its peculiar immunopathogenic mechanisms, but it may provide COVID-19 patients with precious time for activating the antiviral immune reaction or, hopefully, to enhance the effect of antiviral drugs.

The video below from the Morris Animal Foundation is targeted to pet owners and sums up the most recent information on coronaviruses in cats, including that they can catch covid-19 from their owners, and that one early promising treatment is actually the precursor molecule to the covid-19 treatment remdesivir:

While it probably would not have radically altered the course of The Pandemic, what is abundantly clear is that there is much for physicians and researchers to learn from veterinarians, who have warned about the risk of coronaviruses for years, yet struggled with low visibility of their work and chronic lack of funding. In fact, most emerging infectious diseases and pandemics are zoonotic, meaning they spillover from animals to people, and veterinarians are a critical line of defense in recognizing and stopping these threats early. The concept of One Health or One Medicine has become trendy in the last few years, but it is actually hundreds of years old:

The term ‘One Medicine’ was coined by Rudolf Virchow in the late 19th century12 and this remains a cornerstone of 21st century pathology. Virchow is perhaps better associated with the eponymous ‘triad’ comprising the components of venous thrombosis, including venous stasis, activation of blood coagulation and endothelial damage. This triad is a contributor to the multisystem signs and symptoms in both COVID-19 and FIP. One Medicine also forms the foundation of the widely publicized ‘One Health’ triad of people, animals and the environment. The environment is key to SARS-CoV-2 spillover events, whether this is local (eg, in mink farms) or global (eg, in bats and their intermediate host species).

***

The mysteries of why SARS-CoV2 hits some countries—and people—harder than others

While there is much we know about coronavirus biology in general, we have less of an understanding about the wide variability of disease severity across countries, demographics, and individuals. Many people infected by SARS-CoV-2 experience little more than cold or flu-like symptoms, while other patients—sometimes at seemingly random—will develop severe illness and die, or develop Long Covid (which remains difficult to define, diagnose, and treat). How much of this is due to differences in policy or health systems versus individual genetic factors, or just plain luck? We have some theories. Or in scientific parlance, hypotheses.

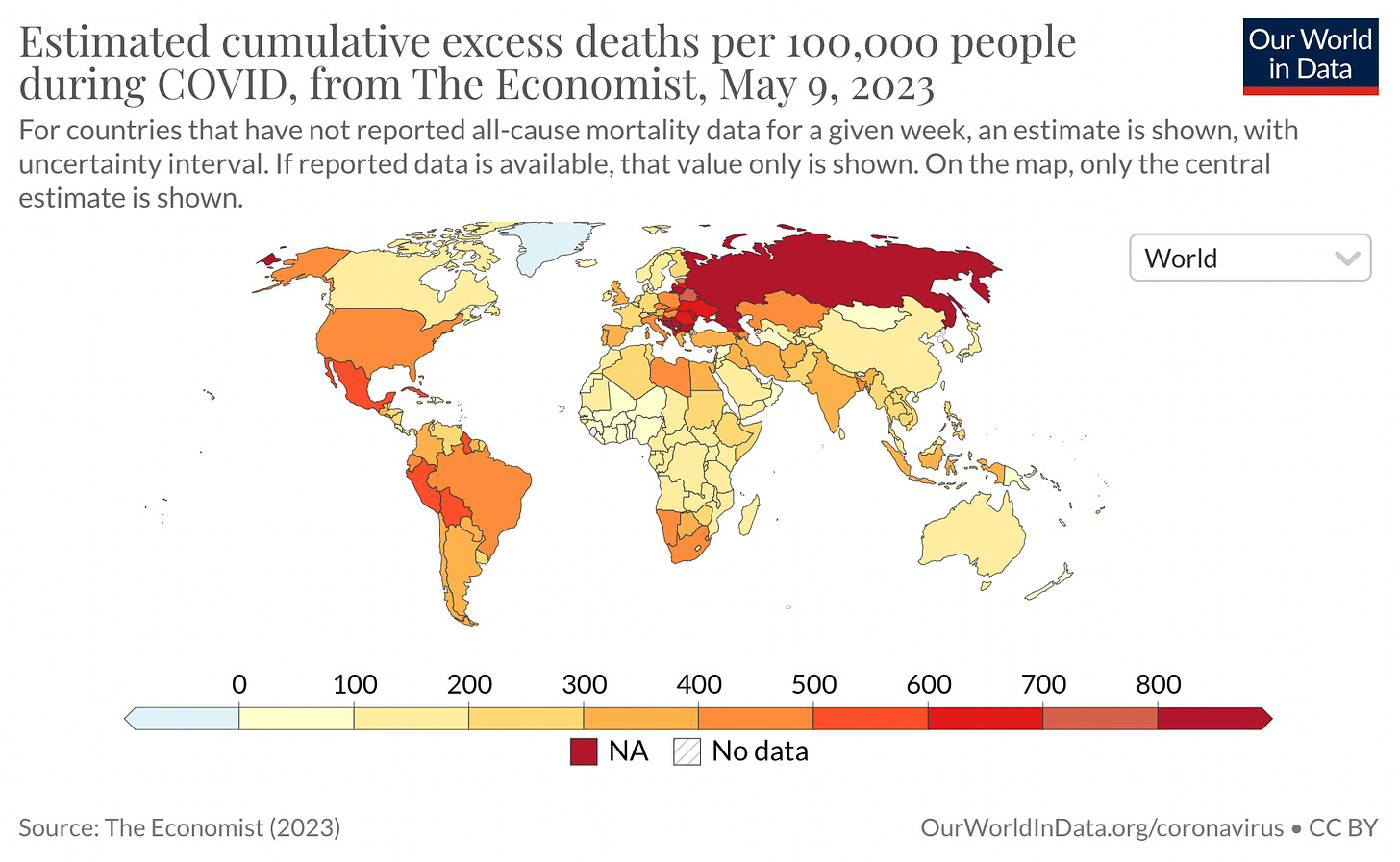

In this New Yorker article, Dr. Siddhartha Mukherjee discusses a number of these possibilities. Perhaps some of the lower-income countries with seemingly paradoxically low reported case and death counts simply lack the testing capability and infrastructure to provide accurate data, or may be trying to hide the severity of the problem? All-cause excess mortality data is probably the most accurate metric we have at this point, and it suggests a statistical mirage is probably not the case. Many countries with extremely limited resources and fragile health systems in Africa and southeast Asia have dramatically lower excess mortality than the United States or other highly developed countries.

Other possible explanations could lie in differences in population density, geriatric care standards, public trust in government, vaccination rates, social distancing and masking, pre-existing immunity to other coronaviruses, obesity rates, access to care, and myriad others, all with varying levels of evidence for and against. In the end, he concludes:

“The COVID-19 pandemic will teach us many lessons—about virological surveillance, immunology, vaccine development, and social policy, among other topics. One of the lessons concerns not just epidemiology but also epistemology: the theory of how we know what we know. Epidemiology isn’t physics. Human bodies are not Newtonian bodies. When it comes to a crisis that combines social and biological forces, we’ll do well to acknowledge the causal patchwork. What’s needed isn’t Ockham’s razor but Ockham’s quilt.

Above all, what’s needed is humility in the face of an intricately evolving body of evidence. The pandemic could well drift or shift into something that defies our best efforts to model and characterize it. As Patrick Walker, of Imperial College London, stressed, ‘New strains will change the numbers and infectiousness even further.’ That quilt itself may change its shape.”

Over a year later, he revisits these questions—particularly the possibility of differences in immune system genetics—in his excellent book “The Song of the Cell,” with a more eloquent distillation of Rumsfeld’s famous quote about “known unknowns”:

“Why, or how, does the virus cause ‘immunological misfiring’? We don’t know. How does it hijack the cell’s interferon response? We have a few hints, but no definitive answer. Is it the timing of the response—the impairment of early phase, followed by hyperactivity of the late phase, the main problem? We don’t know. What about the role of T cells that detect bits of viral protein in infected cells? Could they provide some protection against the severity of viral infection? Some evidence suggests that T cell immunity can dampen the severity of infection, but other studies don’t support the degree of protection. We don’t know. Why does the virus cause more severe disease in men than in women? Again, there hypothetical answers, but we lack definitive ones. Why do some people generate potent neutralizing antibodies after infection, while others don’t? Why do some suffer long-term consequences of the infection, including chronic fatigue, dizziness, ‘brain fog,’ hair loss, and breathlessness, among a host of other symptoms? We don’t know.

The monotony of answers is humbling, maddening. We don’t know. We don’t know. We don’t know.”

***

The success of Operation Warp Speed and new vaccine technology may have long-term benefits

One thing that we do know is that multiple, highly effective vaccines for covid-19 were critical drivers that hastened the end of the acute phase of the pandemic characterized by the greatest sickness and death. Just a few years later we take vaccines for granted, but early in the pandemic experts estimated it could take years for a successful vaccine, and it uncertain that we would even be able to create an effective one. However, the SARS-CoV-2 genome was posted online in January 2020 and Moderna was able to use that to create a prototype mRNA vaccine only weeks later in February, which entered the first stages of safety testing the following month. Pfizer/BioNTech, Johnson & Johnson, Novovax, Astra Zeneca and many others rapidly followed suit in a race for covid vaccine R&D, clinical trials and approval. Operation Warp Speed, which the Trump administration deserves a lot of credit for (you will NOT hear me say that about pretty much anything else they did), smartly funded multiple viable vaccines and pre-purchased doses, as well as streamlined the approval process.

The focused worldwide collaborative effort to rapidly develop vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 represents an incredible scientific accomplishment for humanity. It may soon benefit a wide variety of other diseases. Similar RNA vaccine technology could be used to fight parasites like malaria. mRNA vaccines that target certain types of cancer, including pancreatic cancer and melanoma, are entering clinical trials. Soon, mRNA vaccines may be used in the treatment of diseases as diverse as allergies, heart attacks, and strokes! No one would ever wish for the Faustian bargain of a pandemic in exchange for treatments against other diseases, but it is amazing to see that the technology we built for this crisis is being repurposed for so many other intransigent medical problems.

***

Preparing the world for the next pandemic

Another known unknown is that there will be another pandemic in the future, and many experts fear we are not prepared. Whether it is in one year, a decade, or a century is unknowable. But population increases, climate change, and urbanization encroaching on animal habitats acts like tinder for the fire of zoonotic disease spillover.

The good news is that we know many of the things we need to do to learn from The Pandemic and respond better next time. This Nature special issue lays out many different angles of attack, from improving ventilation, to investing in health system data sharing and running infectious disease drills, to using machine learning algorithms to screen for viruses most at risk of jumping species. The Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response recommends these key steps:

“Stronger leadership and better coordination at national, regional and international level, including a more focused and independent WHO, a Pandemic Treaty, and a senior Global Health Threats Council;

investment in preparedness now, and not when the next crisis hits, more accurate measurement of it, and accountability mechanisms to spur action;

An improved system for surveillance and alert at a speed that can combat viruses like SARS-CoV-2, and authority given to WHO to publish information and to dispatch expert missions immediately;

A pre-negotiated platform able to produce vaccines, diagnostics, therapeutics and supplies and secure their rapid and equitable delivery as essential global common goods;

Access to financial resources, both for investments in preparedness and to be able to inject funds immediately at the onset of a potential pandemic.”

We don’t know what the next threat will be, but we know what to do. Now we just have to get our act together and do it.

Aftershocks

COVID-19 was a shockwave that rippled through society, but its impact was highly unequal. My experiences with The Pandemic pale in comparison to many others. I got sick a few times and recovered uneventfully. No one close to me became seriously ill, disabled, or died. Not everyone was so lucky. I have friends who did lose parents, aunts, uncles, and other loved ones. My college classmates who are physicians in the northeast—especially those practicing in Manhattan—were no doubt scarred by the incessant wail of ambulance sirens and overflowing emergency rooms and ICUs, contrasting with completely silent downtowns. I also inhabit a protected middle class bubble where almost everyone I know is a college-educated white collar worker, a cohort that was more spared by the virus than those who are poor, persons of color, and essential frontline workers who had to risk their health and sanity to serve those of us who could comfortably work from home.

Whether or not we want to be done with The Pandemic and forget those unpleasant years, it is not done with us. Millions worldwide died from covid-19 (and we may not know the full extent for years) or developed longterm complications. An abrupt shift from spending money on services, travel, and leisure to goods that could be enjoyed at home lashed supply chains. A recent study by the National Bureau of Economic Research estimates that covid-19 illness reduced the US workforce by 500,000; along with deaths, early retirements, and voluntary quitting, this is a huge shock to the labor market, and subsequently wages. The initial global economic crash and unprecedented monetary stimulus, combined with the labor shortage, supply chain disruptions, and war in Europe created persistent inflation unlike anything seen in the last 40 years.

Pandemics throughout history leave deep scars and indelibly change society. The Black Death also lead to a severe labor shortage that contributed to the collapse of feudalism, and the widespread mortality precipitated changes in religiosity and may have catalyzed the Renaissance. European resistance to smallpox and measles from centuries of exposure, followed by transmitting those pathogens to the Americas, Africa, and Asia fueled the imperialism and colonialism of 17th to 19th centuries. The Great Influenza pandemic of 1918 preceded a decade of economic boom times in the Roaring Twenties and conceivably tipped World War I in favor of the Allied powers.

The next pandemic is inevitable, but we don’t know when or where it will happen, or what the pathogen (and likely animal reservoir) will be. These are the known unknowns of global epidemiology. Despite the uncertainty, we can—and should—use the tools above to increase our readiness for the next emergent infectious disease. Of course, there will always be periodic “Black Swan” events that were so bizarre, no one thought to prepare for them; those are the unknown unknowns that keep me up at night.

Really excellent report! You cover all the significant bases. I've been saying much the same things for the last three years and been termed an alarmist or a "covid maximalist.". Back in 2020 when it became clear it was pan-species event and highly mutagenic to boot, I was telling friends in social media that this virus had the capability to bring down our civilization. It didn't. But the mutations will keep coming; there's a huge Zoonotic pool. And eventually we may see variants swapping RNA with other viruses in patients with coinfections. It's far from over. BTW for me personally it's far from over- I'm in my third year of dealing with lingering damage from my original infection in March,/April of 2020.