Quitting Time

Reflections on leaving clinical practice

My patient was dying. She lay on her side in the emergency triage area, hyperventilating as much as I was while I tried to figure out what was wrong. To go along with the rapid shallow breaths, the dog’s pulses were fast and weak, her blood pressure nearly unreadable, and her gums were pale. Giving multiple boluses of IV fluids did not help her. A blood gas confirmed what was obvious: the dog was not getting enough blood and oxygen to tissues throughout the body. Clearly, she was in shock, but why?

The referring veterinarian’s working diagnosis was lymphoma based on finding enlarged lymph nodes on their exam. The dog also had a distended abdomen that felt like it contained abundant free fluid floating outside of the organs (ascites). While my physical exam skills were rusty, and I didn’t completely trust them, my brief ultrasound of the belly confirmed the abdominal effusion. This could provide a clue towards the underlying illness. Based on the severity of the patient’s shock and lack of response to basic stabilization, my gut told me there was an infection hiding, the dreaded septic abdomen emergency.

I carefully inserted a needle hooked up to sterile tubing into the patient’s abdomen with ultrasound guidance to avoid piercing any vital internal organs. To my surprise, rather than a thick or cloudy fluid (which would support an infection or potentially cancer), the fluid that came out looked like straw-colored water. After preparing slides for evaluation under the microscope, there was no evidence of either tumor cells or an infection. I was no closer to an answer.

Clearly, she was in shock, but why?

“What’s wrong with this dog?” asked veterinary technicians assisting me with this case, among the dozens of others in the hospital that night. It was July, and the only other doctor in the practice was a brand-new intern who was on her very first overnight shift. She was running around overwhelmed with her own cases and asked me for my opinion on some of her cases. Frazzled, I barked unhelpful generalities. As the “senior” doctor, I was supposed to have all the answers. But the reality is I had no idea what was wrong with this patient, and time was running out.

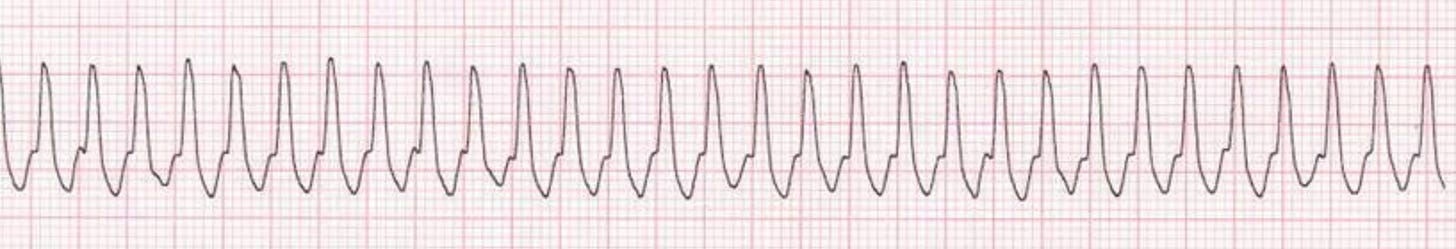

One of technicians who was rechecking the vital signs on my critical patient mentioned the pulse rhythm was intermittently irregular. I checked behind her, and agreed; at times it felt fast yet normal, while in other stretches there would be abnormal spaces between beats. We pulled over the ancient EKG machine and hooked up the electrodes. As the machine spit out paper with a tracing that indicated the heart’s electrical activity, part of the puzzle became clearer—instead of the normal gentle repetitive waves of a healthy heart, there were terrifying jagged scribbles:

This was ventricular tachycardia, a life-threatening arrhythmia. It could easily explain the patient’s state of shock. It was so simple, yet I had overlooked this possibility. I cursed myself for being so stupid. We drew up a syringe of lidocaine, a drug that can dampen overexcitable heart and neural impulses, and pushed it slowly into the patient’s IV line. Within seconds, almost like magic, the patient’s heart slowed towards normal, and the abnormal beats disappeared. The EKG tracing became normal. My patient stirred from laying on its side like a limp rag to sitting up on its chest and looking around the room.

As the senior doctor, I was supposed to have all the answers. But the reality is I had no idea what was wrong with this patient

Now that she was more stable, I needed to find out what was wrong with the heart. I took the dog into the ultrasound suite to peek inside the chest (which in retrospect I should have done as part of the initial assessment). As soon as I put the probe between the ribs the problem was obvious: there was a large amount of fluid in the sac surrounding the heart, the pericardium. Cardiac tamponade. This life-threatening condition often arises in dogs when cancer within the pericardial sac that surrounds the heart, particularly hemangiosarcoma (a malignant vascular tumor), bleeds and squeezes the heart to the point where it can’t adequately pump blood anymore.

The immediate treatment for tamponade in both human and veterinary medicine is to insert a disturbingly long and large-bore needle into the space around to heart to drain the fluid and relieve the pressure. A technician and I put our patient on her left side, clipped the hair in a large square window over the heart, and prepared the skin with surgical scrub. Then, sweat beading on my brow, I carefully inserted the 5 and ¼ inch needle behind the 3rd rib and advanced until I felt the characteristic pop. Dark black-red blood gushed through the needle and into the collection set for measurement and analysis. This blood refused to clot, which is characteristic of blood trapped in spaces like the pericardium, unlike fresh blood (say, from accidentally slashing a vessel during the procedure).

When we rechecked her chest and abdomen with ultrasound a short time later, her free fluid had disappeared; relieving the pressure had fixed the “plumbing problem” in the heart, at least temporarily. Assuming the most likely scenario, that this hemorrhage into the pericardium was due to a form of cancer, it would certainly return in time. I took off my bloody gloves and wiped my forehead. “I’m a pathologist, not an emergency vet. What am I doing here?” I thought to myself.

I didn’t start out interested in pathology. I spent summers in college working with assistance dogs for the hearing impaired, a small animal general practice hospital, and several dairy farms. As I entered veterinary school and was exposed to all the diverse specialties and subspecialties in the profession, the biggest challenge in finding my niche was that everything interested me—anatomy, physiology, endocrinology, hematology, radiology, surgery, and more. By the end of vet school, I had a plan: I would pursue a rigorous internship in small animal medicine and surgery after graduation. Internship year would be a baptism by fire where I would see a ton of cases rotating through multiple different specialties, and allow me a chance to explore my interests and see where they took me.

The “rigorous” aspect of my internship did not disappoint. I was responsible for receiving overnight cases for three to four week stretches at a time. Some nights nothing came in and I would watch TV, itching with boredom. Other nights I had to juggle just under a dozen different emergencies as the only doctor in the hospital. I frequently felt overwhelmed, unable to prioritize, and incompetent. My evaluations on ER performance were satisfactory, but as a perfectionist, I felt like I failed any patient I could have done better on (which was most of them).

While, there were many rotations I performed well on, there were problems on others. On several occasions supervising senior students performing routine “spay” surgeries I provided incorrect surgical instruction, and while there were no adverse outcomes, some of the faculty felt I should no longer be involved in this aspect of teaching students. As someone who was a tutor in vet school and loved teaching, this was a crushing blow to my self-confidence. There was an incident where, coming off 30 hours of ER overnight call onto our routine preventative medicine service, I mixed up the vaccines for a veterinary student’s own dog, and they were irate. Several clients complained about my bedside manner, including one memorable owner that lamented I didn’t respect their New Age beliefs that their critically ill dog could be healed with crystals and prayer.

I was placed on probation, allowed to keep seeing patients, but under greater faculty supervision for the duration of the probationary period. Some faculty made sharp and borderline unprofessional comments about my education and performance. Luckily, I had several supportive mentors who saw some potential and encouraged me to keep working to improve as a doctor.

These incidents rattled me as they added up. I faced bouts of shame, self-doubt, and even clinical depression. More than once, I asked myself: Where is the line between the normal rough patches in medical training and genuine incompetence? Were any of my flaws as a doctor, particularly those of temperament, even correctable? Or was I simply a lost cause? I also wondered how much of this was the incidents themselves versus how I responded to them. I have struggled with anxiety and depression for much of my adult life, seeing various therapists and intermittently taking medication.

Where is the line between the normal rough patches in medical training and genuine incompetence?

I later learned that to a degree, these thoughts and feelings are extremely common among veterinarians. According to a study published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 24.5% of male and 36.7% of female veterinarians disclosed having one or more episodes of depression in an anonymous survey, and 14.4% (men) and 19.1% (women) contemplated suicide.1 These mental health struggles likely contributes to veterinary medicine’s risk of suicide that is double that of dentists and physicians and quadruple the general population.2 Even more than the typical veterinarian, an intern faces the added pressures of a steep learning curve, sleep deprivation, low pay, switching gears between different specialties every few weeks , and applying for residencies a few months into their programs.

According to a study published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 24.5% of male and 36.7% of female veterinarians disclosed having one or more episodes of depression in an anonymous survey

As summer turned to fall, the dates for applying to clinical residency programs approached fast, but I shrunk from the possibility. Hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt and almost 10 years spent training, I needed to find some way to use my veterinary degree, and began to consider non-clinical careers.

Facing the deadline for residency applications, I decided to apply to clinical pathology programs. My logic was that clinical pathology was a specialty on the brink of the clinical and non-clinical worlds requiring similar skill sets. I would still be poring over labwork and samples from patients, and I would need to incorporate the clinical findings of the veterinarians working the case to arrive at the right diagnosis. I would still be “solving the puzzle.” Most importantly, I told myself this information would matter to the clinicians, the animals, and their families. Unlike my colleagues down the hall in anatomic pathology, who spend much of their days conducting autopsies on the deceased, my “patients” would still be alive, and desperately awaiting a diagnosis. I would not be abandoning my training in clinical medicine altogether.

Shortly before Christmas of my intern year, I was accepted into a program that combined a clinical pathology residency with a graduate degree leading to a PhD. At this point, I still had slightly more than half of my internship to complete. But after my residency acceptance, something changed. The shifts seemed a little easier. My performance on rotations increased. The clouds of depression lifted. I can’t say for sure why this had such a positive effect on me. Maybe it was simply relief at finding “light at the end of the tunnel” and a new—hopefully better fitting—career on the horizon. Maybe it was validation that even though I’d been through ups and downs as an intern, I still had some value as a veterinarian. That I wasn’t a total screw up. Either way, my attitude, and evaluations, brightened.

When I started my residency, I took to it like a natural. I loved all the aspects of it, from evaluating blood and tissue under the microscope, to teaching future veterinarians how to interpret laboratory tests. I forged a close working relationship with the specialists on various services, and quickly established myself as a pathologist who would go the extra mile for a patient. I developed an ambitious research project and started writing grants to fund it. I was happy to be doing something I not only enjoyed, but excelled at. Still, something felt off. Something was missing.

Beneath the surface of professional success, discontent lingered. Part of me felt like a failure for abandoning practice so quickly. What would have happened if I had given myself a little more time to adjust to clinical practice, and a lot more self-compassion about my mistakes? Had I made a rash decision based on a few bad experiences? Now a resident, I had watched troubled interns blossom into excellent veterinarians with mentoring and time.

What would have happened if I had given myself a little more time to adjust to clinical practice, and a lot more self-compassion about my mistakes?

I started moonlighting as an emergency veterinarian in my first year of pathology residency. The nominal reason was simple: I needed more money. Veterinary students, along with law students, are well-known to incur gargantuan amounts of debt for their professional training. According to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA), the average student debt for veterinary students in 2016 was $167,534.89, and more than 1 in 5 had greater than $200,000 in loans. I was significantly worse off than even that average from lingering undergraduate debt and attending an out of state veterinary school, with more than $300,000 in student loan debt. Compounding the problem was the other side of the equation—low income. While the general public may know human physicians are underpaid during their training after medical school from TV shows like Scrubs or Grey’s Anatomy, the situation for veterinary house officers is significantly more dire—I made about $27,000 during my rotating small animal internship, and my resident’s salary was barely higher at $31,000. Between student loan payments, rent that took up about half of my take-home pay, and other living expenses, I was hemorrhaging money and my credit score was anemic.

After several months of being broke and dipping into credit cards for groceries and essentials, I heard rumblings that a few of the previous clinical residents had supplemented their salary by moonlighting as emergency veterinarians in some of the cities the next state over, outside of our referral radius. They told me what they made, and the pay was good. I wrestled with the pros and cons of this emergency relief work.

Besides the financial aspects, there were other, more complicated, motivations for continuing clinical practice while I trained to be a specialist in pathology. It would be a way I could keep some semblance of a connection to the clinical world, and I told myself it would make me a better pathologist. On the other hand, I would likely see all my old insecurities and flaws rush back. What if I was too rusty and out of touch? What if I made a catastrophic mistake and a patient died? These doubts rushed through my mind, counterbalanced by the fact that I (barely) survived a difficult internship just a few months prior. Going back to practice on a limited basis seemed like one way to answer the question once and for all: Could I be a successful practicing veterinarian? After a few weeks of internal debate, I applied for the relief job.

A few hours after removing the bloody fluid from around my patient’s heart, the critical care specialist came in for morning rounds and we discussed the case. He offered to do a recheck ultrasound of the chest. With a few twists of the probe, he identified a tumor in the right side of the heart. “Yep, looks like a mass right there.” He pointed it out on the screen. “Probably hemangiosarcoma. Looks like you got all the free fluid out, good catch.” He offered a few more pointers on case management, then moved on to the next patient.

As I was writing up my records, I had mixed emotions. On the one hand, I eventually arrived at the correct diagnosis, and the patient was doing better, for now. The dog would be discharged and the owners would get some quality time with their friend, and that was certainly a good thing. On the other hand, I almost misdiagnosed an obvious disease, one I was sure a more experienced and competent emergency veterinarian would have quickly caught. This was a near-miss event, and I didn’t feel good about it.

I also remembered how irritable I was during the shift, and how I had snapped at the intern when she asked simple questions about managing her own cases on her first overnight shift ever. I had become like a few of the residents and faculty I remembered less than fondly during my internship: impatient, dismissive and not particularly helpful. I wondered if this was how decent people became bad mentors: One rough shift at a time.

I had worked weekend and holiday emergency shifts for the past four years, staying up to all hours of the night triaging cases, managing treatment plans, and interpreting images on patients that ranged from barely ill to the edge of death. I enjoyed the work, and felt pride in being a lab jockey who was still able to work as a “real” veterinarian. My ER relief supervisors evidently liked having me around, even emailing me shift preferences before the other doctors in the relief pool. But over time, slowly but surely, I felt my clinical skills had atrophied. “This case was a win, but what about the next one?” I wondered. I wanted to go out on a high note, not get pressured into quitting after a catastrophic mistake. I realized it was time to hang up my stethoscope. Driving home from that shift, I felt melancholy. It was the last time I would ever work as a clinical veterinarian. I emailed my resignation notice later that evening.

I’m glad for the time I spent in practice, both as an intern and an emergency veterinarian. Money aside, the experience really did make me a better pathologist. I was able to know what the clinicians “in the trenches” were looking for, how important each test was, and why they made decisions that could seem perplexing from the isolated viewpoint of the laboratory. It gave me greater empathy for the frustration they felt on their end when facing angry or grieving clients with inconclusive tests and diseases that eluded definitive diagnosis despite everyone’s best efforts.

With the benefit of hindsight, I’ve come to terms with my skills and flaws as a veterinarian, both as a (formerly) practicing clinician and as a pathologist. Those extra years of relief work showed that on the most basic level, I could do the job. There were certainly better emergency veterinarians than me. I also received referrals from veterinarians far worse. But beyond the question of could I do the job was should I? Seeing a high-volume of cases with financial pressures and difficult owners was incredibly stressful. These factors, along with the incredible debt burden and (relatively) low monetary compensation, almost certainly contribute to the suicide epidemic among veterinarians in the United States. I did not want to become a statistic. My neuroses, perfectionism, self-doubt, and difficulty managing grace under pressure are the exact opposite of the flexibility and resilience needed to survive as a modern practicing veterinarian.

I no longer feel like a failure as a veterinarian. The time I spent in practice helped make me who I am professionally today. I like what I do, and I’m good at it. Since my time in the ER, I’ve done research and teaching in academia, practiced as a diagnostician and R&D manager in a large corporate lab, started and sold several small businesses and start-ups, and now I’m traveling the country as an independent contractor. My work indirectly helps patients and their family veterinarians. And that’s good enough. Some days, I think that embracing more of the “good enough” mindset, as opposed to viewing any mistake as a personal failing, could have made the journey less difficult all along. I should remember to tell that to the next panicked intern that comes through the lab on a particularly rough shift.

References:

Nett RJ, et al. “Notes from the Field: Prevalence of Risk Factors for Suicide Among Veterinarians — United States, 2014.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). 2015, 64(05);131-132.

Bartram DJ, Baldwin DS. “Veterinary surgeons and suicide: a structured review of possible influences on increased risk.” Veterinary Record (2010), 166: 388-397.

Image credits:

EKG: “Reading ECGs in veterinary patients: an introduction.” DVM 360, Meg M. Sleeper, VMD, DACVIM (cardiology), January 29, 2020

Pericardiocentesis: “Pericardiocentesis.” Clinicians Brief, April L. Paul, DVM, DACVECC, June 2016

Echo: “Canine Pericardial Effusion” Clinicians Brief, Nancy J. Laste, DVM, DACVIM (Cardiology), January 2016

Thanks for writing that. I too had a rough go on clinics and left for 12 years to do food safety (I did not have a PhD in me). I consulted and traveled the country helping set up local food businesses.

I went back to clinics 2 years ago after a TON of therapy and coaching. I love it now. I even work ER. I am not a perfect doc, but I am studying for DABVP boards and really enjoying the process.

Thanks for this article, Eric. I recently retired from small animal practice but spent most of my career with imposter syndrome, especially with regards to surgery. Never mind I never had an actual disaster, but I never felt hugely confident. I’m so glad you found your niche. I adore clinical pathology, especially cytology, thanks to great CE from Kate Baker, and so much wish I had known these careers were options back in the late 80s when I started out. Still, small animal medicine was my thing for so long, and it was weird hanging up my stethoscope. I wish you all the best...looks like you are where you need to be!