Research Roundup: Hematology Factoids

Some quick info about CBCs & blood smears for busy vet professionals

Hey everyone,

One of my missions with this Substack is to promote veterinary research and make it accessible to a wide audience. You are all busy people, so it’s important to keep these short and simple! I have done this through several different post formats, including deep-dives into a specific topic and the “5-minute paper” synopsis of a single study. Today I am trying out a new format that is closer to a research digest: I will post a number of useful factoids you can commit to memory followed by a couple paragraphs of explanation and links to the studies for interested readers.

For this inaugural research digest I picked hematology, one of my favorite topics in clinical pathology, and an area where I often get questions from referring vets. Most of the factoids today will be free to all readers, but I did put a few behind a paywall as a bonus to readers who have generously chosen to upgrade their subscription.

I hope you enjoy this new article format! Let me know your feedback in the comments or shoot me an email.

—Eric

When bands > segmented neutrophils, your patient is in trouble

This is called a “degenerative left-shift” (DLS) and for years we taught that this was a negative prognostic indicator. The mechanism made sense—the body was being overwhelmed by demand for white blood cells and couldn’t keep up—but it was mostly theoretical and based on anecdotal experience.

Several retrospective studies out of UC Davis found that this phenomenon is indeed linked to worse outcomes in both cats and dogs. In canine patients it was associated with almost twice the risk of death or euthanasia in hospital (Hazard Ratio 1.9), while in cats the HR was 1.57, suggesting ~60% increased risk of death.

That being said, no single prognostic factor is the end-all-be-all that should be taken as a death sentence: the worst example of a DLS I ever saw was in a dog thrown from a pick-up truck with extensive skin degloving wounds, yet they recovered, were adopted by one of our hospital’s nurses, and lived many years!

Studies:

Burton AG, Harris LA, Owens SD, et al. The prognostic utility of degenerative left shifts in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2013;27(6):1517-22

Burton AG, Harris LA, Owens SD, et al. Degenerative left shift as a prognostic tool in cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2014;28(3):912-7

Heat stroke does weird things to the blood 🥵

It is fitting to talk about heatstroke in the middle of what has been another summer of record-breaking temperatures. Heatstroke causes damage throughout the body, ranging from dehydration to problems with the heart, muscles, and other organ systems. One thing people may be less familiar with is what too much heat does to the blood of dogs and cats (and probably people, although I’m not familiar with the human literature!)

For one thing, it causes inappropriate release of nucleated red blood cells (nRBCs), termed rubricytosis or normoblastemia. Severe heat damages blood vessels in the spleen and bone marrow so that they can no longer hold in those immature precursors. nRBCs were significantly higher in dogs with heatstroke that died compared to survivors, and a cut-off of 18 nRBCs/100 WBC was 91% sensitive and 88% specific for mortality.

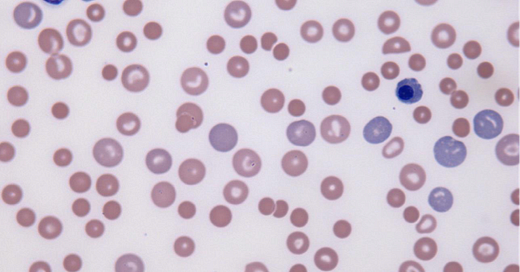

Heatstroke—and increased body temperature from severe fevers and drugs like Adderall and methamphetamines—can also induce abnormal degenerative changes to white blood cells as seen below. Keep in mind that these can also be artifacts caused by blood stored or shipped in high heat without appropriate refrigeration!

Studies:

Aroch I, Segev G, Loeb E, et al. Peripheral nucleated red blood cells as a prognostic indicator in heatstroke in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2009;23(3):544-51.

Mastrorilli C, Welles EG, Hux B, et al. Botryoid nuclei in the peripheral blood of a dog with heatstroke. Vet Clin Pathol. 2013;42(2):145-9.

Iron Deficiency Anemia can be (highly) regenerative!

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is fairly common, but often overlooked by clinicians in my experience. One of the reasons seems to be the belief that it is always non-regenerative. In fact, IDA can range from weakly to strongly regenerative. In one study out of Cornell, all but two of the dogs with iron deficiency (labeled FeDef in the figure) had a reticulocytosis, with the majority being highly regenerative at >200,000/uL reticulocytes:

Numerous factors can influence the degree of regeneration in IDA, including the length of time it has been developing and the underlying cause. Nutritional iron deficiency is more commonly poorly- or non-regenerative, whereas IDA resulting from chronic blood loss (most common in adult animals) is associated with reticulocytosis. This is illustrated in the figure below from an experimental study in rats that mirrors data in people and my anecdotal experience with dogs and cats:

The big take home point here: Don’t write-off the possibility of blood loss and IDA just because your patient has a regenerative anemia! This is especially true if they have other classic indicators like microcytosis (low MCV).

Studies:

Schaefer DM, Stokol T. The utility of reticulocyte indices in distinguishing iron deficiency anemia from anemia of inflammatory disease, portosystemic shunting, and breed-associated microcytosis in dogs. Vet Clin Pathol. 2015;44(1):109-19.

Burkhard MJ, Brown DE, McGrath JP, et al. Evaluation of the erythroid regenerative response in two different models of experimentally induced iron deficiency anemia. Vet Clin Pathol. 2001;30(2):76-85.

BONUS factoids after the pay-wall:

The ProCyte CBC analyzer can misclassify white blood cells

The constellation of lab findings that should worry you for histiocytic sarcoma

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to All Science Great & Small to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.