I’m finally getting around to reading The House of God, the classic satirical novel about the beauty and horrors of medical training. The author is “Samuel Shem,” the pen name of Stephen Bergman, MD, PhD. It is a black comedy roman-a-clef full that follows narrator Dr. Roy Basch as he struggles to survive his intern year at Beth Israel Hospital affiliated with Harvard Medical School (thinly disguised as “The House of God” and the “Best Medical School” or BMS). After this tumultuous year, Basch—like Dr. Bergman himself—decides to flee internal medicine for psychiatry, a field he considers more humanistic and compassionate.

The novel provides an unsanitized look at the practice of medicine, full of gallows humor. It is also a product of its time (the 1970s) and some of the passages haven’t aged well—there is definitely enough un-PC material on sex, gender and race that I’m confident it could not be published in 2024. Yet it persists because it is full of wit and wisdom.

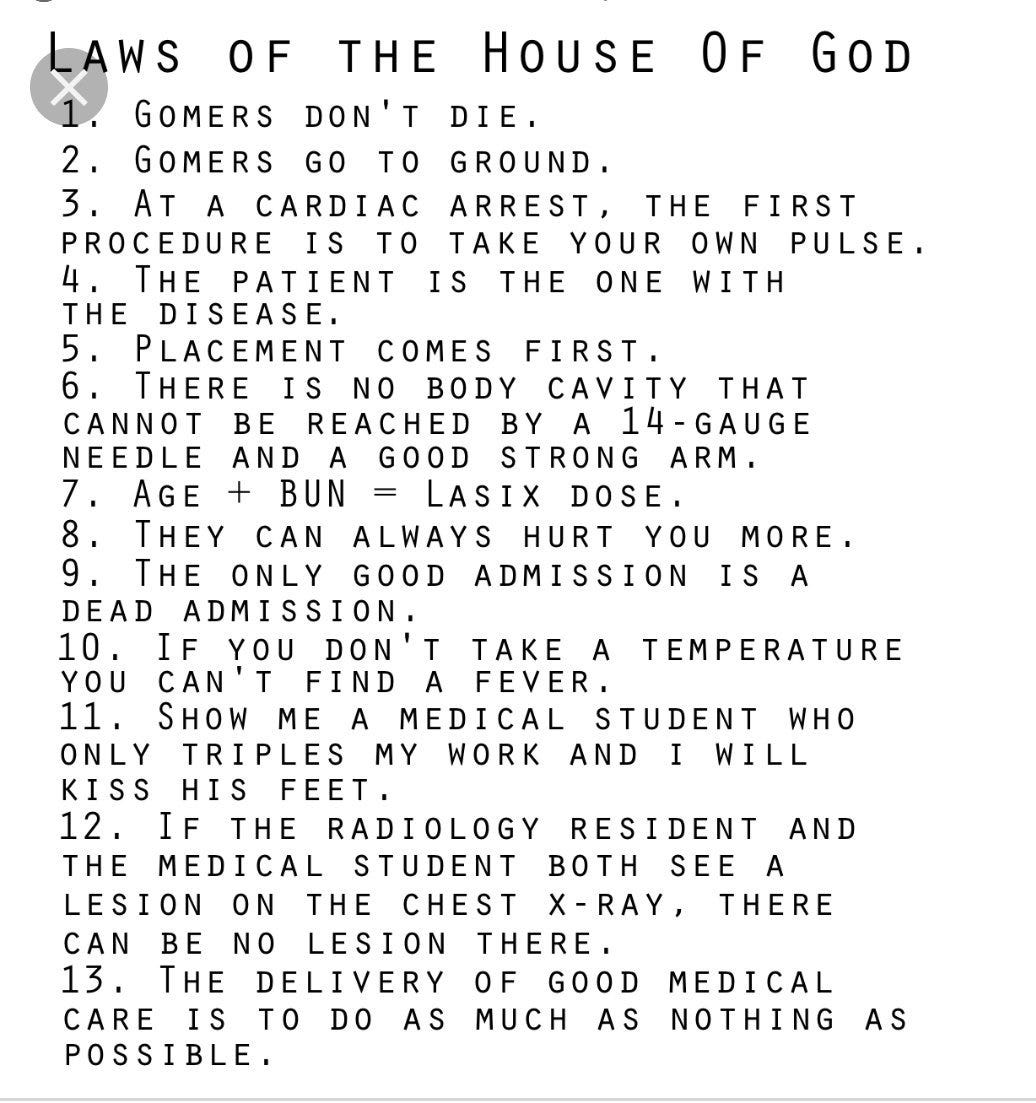

Whether or not you have read the book, you are likely familiar with its cultural impact: themes and references from The House of God—sometimes verbatim quotes—are found in TV shows like Scrubs, House, Gray’s Anatomy, and plenty of others. Terms like “GOMER” (Get Out of My Emergency Room) and “turfing” originated here. Some of the most famous parts of the book are the THE LAWS OF THE HOUSE OF GOD preached by Basch’s cynical but wise mentor, “The Fat Man”:

Over the years I have accumulated a handful of pithy sayings about lab medicine that I decided to share with you, my own…LAWS OF PATHOLOGY.

Enjoy!

#1: GARBAGE IN, GARBAGE OUT

In an example of medical lessons that are also life lessons, how much you get out of pathology depends on the amount of effort you put in. Cytology and biopsies heavily depend on the quality of the sample and submission information. If you send me slides full of ruptured goo (that’s the technical term), I will not be able to tell you very much. Same goes for if you don’t provide any history or description of the lesion. As the legendary pathologist Paul Stromberg was fond of saying: “I can’t diagnose Feline Infectious Peritonitis unless you tell me it’s a cat!”

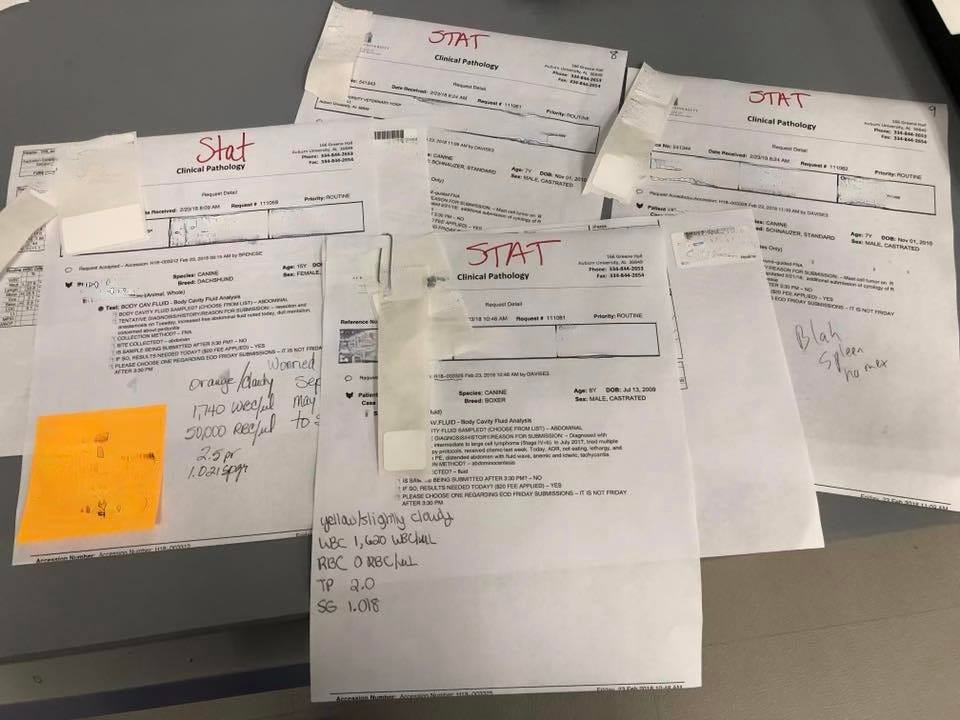

#2: IF EVERYTHING IS “STAT”, NOTHING IS STAT

This one could almost be a Zen koan. We drop everything for STAT samples—those extremely time sensitive cases on which surgical go/no-go or chemotherapy or euthanasia decisions hinge; they jump the queue ahead of everything else.

What happens when there are two STATs at once? Well, if you have residents you can divide and conquer. But what about 3 STATs at once? More? (My personal record is SIX simultaneous “STATs” 🙃).

This is where we run up against the practical limits of what one or a few people people can do. Everything can’t be the same level of urgency, yet everyone thinks their case is the most important. This is where choices have to be made on what is relatively more urgent than something else—triage.

Like in the laboratory, the emergency room, or life itself, the art of triage is everything. We each have only two eyes, two hands, one heart, and 24 hours in a day. Every minute we choose to spend on one thing means we are choosing not to do something else.

#3: THE MORE EXCITED THE PATHOLOGIST, THE WORSE THE PROGNOSIS

We pathologists are an odd breed; we marvel at the microscopic appearance of grave diseases like cancer and exotic infectious organisms, the rarer the better. After you’ve looked at tens of thousands of cases (and orders of magnitude more slides than that), everyday benign lesions like lipomas and cysts just don’t get your heart rate up anymore. Whether you are a patient or the clinician managing a case, you do not want your pathologist calling to tell you how “interesting” the biopsy is 😬

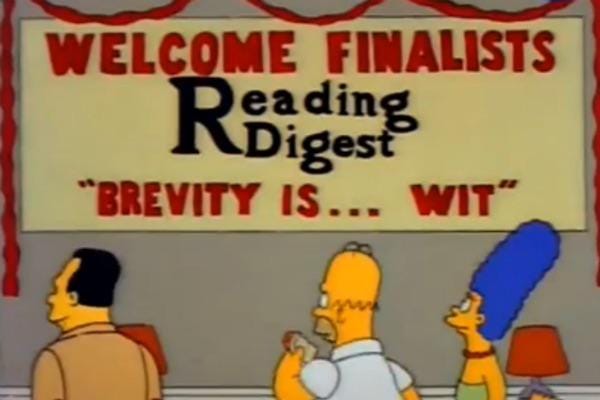

#4: THE LENGTH OF THE REPORT IS INVERSELY PROPORTIONAL TO THE CONFIDENCE OF THE PATHOLOGIST

This one is a close corollary to LAW #3. When most pathologists know the diagnosis cold, they “bottomline” it without any caveats or equivocation. However, when we have a case that is giving us heartburn or we don’t know what the hell is going on, that’s when we channel William Faulkner and write page after page of purple prose with run-on sentences. If you open up the medical record and read the dreaded SEE COMMENTS, you’re gonna need to do some follow-up investigation…

#5: “IN MY EXPERIENCE” = ONCE, “IN CASE AFTER CASE” = TWICE

This one applies to pretty much all doctors. The joke means we tend to exaggerate how often we have seen something rare to sound more authoritative. At the end of the day, “the plural of anecdote is not data,” and we should really be basing our decisions off of good quality studies, rather than one-off stories whenever possible. When we can’t, we should at least be humble about the limits of our knowledge. Let’s normalize saying “I don’t know” and “Hmm, I’ve never seen something exactly like this.”

#6: NEVER MAKE A CELLULAR DIAGNOSIS WITHOUT LOOKING AT A CELL

This one drives pathologists nuts. I’ve seen so, so many cases where people make very specific microscopic diagnoses based on clinical intuition, the physical exam, imaging etc, only for the results to be completely different when it is biopsied. As I like to say, “Your eyes aren’t microscopes” and you usually can’t reliably tell what type of tumor something is based on the gross appearance alone!

All Science Great & Small is a reader-supported guide to veterinary medicine, science, and technology. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription 👇

#7: IF YOU DON’T KNOW WHAT A CELL IS, JUST CALL IT A MACROPHAGE AND YOU’RE PROBABLY RIGHT

This one goes out to my residency mentor at Auburn, Dr. Pete Christopherson. Like many other LAWS in this post it’s a bit flippant, yet it comes in handy more than I’d like to admit. Macrophages are one of the most diverse cells in the body from a molecular, immunological, and morphologic standpoint, and they get even crazier when activated in chronic granulomatous inflammation. Histiocytomas and histiocytic sarcoma are tumors related to macrophages and they can look even more bizarre.

#8: THE CRAZIEST CASES COME IN AT THE END OF DAY

Like people who swear that the emergency room is extra crazy on a full moon, it seems to be a consistent pattern in many labs that the most interesting—and challenging—cases arrive at the end of the day. There are probably multiple reasons for this phenomenon. One is a simple matter of workflow: more complex samples like organ biopsies are sampled through invasive procedures that require anesthesia, imaging, and coordination between services. Similarly, the sickest cases come in through urgent care and ER at all hours of the day, unlike more stable patients that show up to a regularly scheduled appointment. Finally, after a long day of reading flat after flat of cases, there is bound to be a mental exhaustion factor, and even straightforward cases may seem a little tougher than usual. Remember LAW #2 and LAW #8 when calling the lab at the end of the day!

#9: “NON-DIAGNOSTIC” IS DIFFERENT THAN “NOT DIAGNOSTIC FOR”

When pathologists call a sample “non-diagnostic” they mean it can’t be interpreted. Either there is no tissue, or it is all damaged, or some other problem makes a diagnosis impossible. However, I often hear clinicians say “Oh yeah, that lymph node report came back non-diagnostic” when it simply didn’t agree with their hunch (see LAW #6). For example, if they suspect lymphoma, yet the slides are great quality and look like benign inflammation, that wasn’t “non-diagnostic,” it just wasn’t diagnostic FOR lymphoma! It can be frustrating to spend a ton of time and effort on a case only to see your work referred to later as essentially worthless, so keep this in mind when communicating with your friendly neighborhood pathologist to maintain the best relationship.

#10: IT DOESN’T HAVE TO MAKE SENSE

Finally, I find myself repeating this one often to residents and younger veterinarians. We all want cases to match what we learned in our lectures and textbooks, but sometimes they just…don’t. We are trying to cram messy biology into a small box of diagnostic labels and it does not always fit. Sometimes we never even get a final answer and have to live with the uncertainty.

This isn’t to say we don’t know anything at all and should throw the rules out the window, only that you are going to quickly become disappointed and frustrated if you expect everything to add up to an airtight conclusion in every case. One of the best, and worst, parts of pathology is how many diseases remain a mystery despite hundreds of years of medicine and research.

There you have it, my ten LAWS OF PATHOLOGY. I hope you find some of them useful, or at least amusing. Let me know in the comments what additional LAWS you might propose!

#4 made me laugh!

Great post, Eric!

I laughed out loud.

For in house pathology...the number of "cocci" on the slide is directly proportional to the last time someone changed the Diff Qwik.

And for God's sake...why on earth does everything have to be done on oil immersion?!! I hate that setting so much because by the time I get to the slide after the techs it is a gloppy mess. Plus it gets all over everything