Veterinary Medicine is Becoming a Luxury Product

Aggressive pricing strategies to maximize profit jeopardize our industry

The COVID Boom for Luxury

A recent industry report by McKinsey discusses market trends in luxury goods (watches, handbags, jewelry, fashion, etc) over the past 5 years. This sector surged in sales to over $400 billion, with an average 5% annual growth rate. Behind this trend was all of the people stuck at home with disposable income to spare, unable to spend it on restaurants, vacations, etc. A key question is what accounted for more of the growth in luxury goods during this time: absolute number of sales or item price increases? It turns out almost entirely the latter:

Price increases accounted for more than 80 percent of growth during this period, while volume gains were more moderate.

In other words, a relatively small number of people were paying much more for the same goods, which drove those record revenues. This should not be totally surprising, as luxury goods and services are defined by several traits:

Not necessary for life, but highly desirable

Demand has positive elasticity (tends to go up as income rises)

Typically have a large mark-up (i.e. high profit margin)

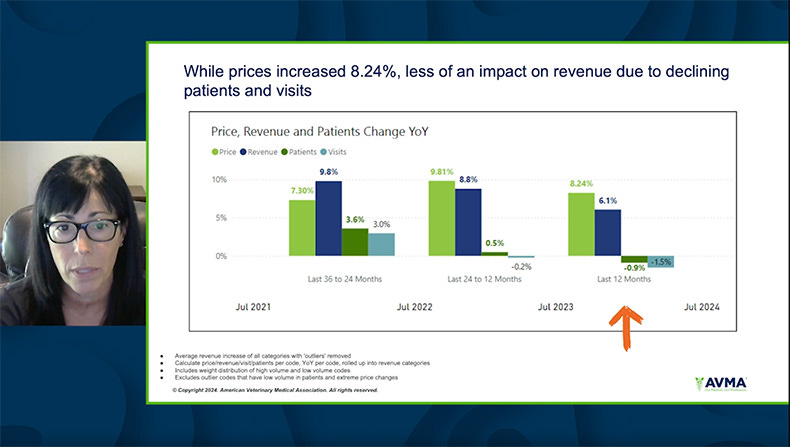

When I read about the dominance of price increases over volume increases for luxury goods, I got curious to see how it compared to veterinary medicine. This is what I found:

These numbers didn’t surprise me. My experience taking my own pets in for both wellness and specialty care over the last few years has been one of continuous sticker shock, and I’m in the industry. I’ve seen estimates for 24-hours of basic supportive care that were ~$5,000. Advanced surgical procedures and critical patients hospitalized for days can easily cost five-figures. While I understand that pet ownership is a privilege, and not everyone can afford specialty care, IMO you shouldn’t have to take out a home equity loan to afford surgery for bloat or a slipped disk!

Aggressive Pricing Strategy

What’s going on here? I want to start by saying there are many legitimate reasons for these COVID-era price increases, especially in the first couple years of the pandemic:

Huge increase in demand for pet services

Lots of people adopted pets to pass the time

Working from home let people notice more medical issues

Supply chain shocks raised costs for drugs, fluids, equipment, etc

Inefficiency of social distancing and curbside delivery models

Rising labor costs

Pay raises to account for inflation

Attrition of vets and techs due to burnout (especially in ER)

However, from 2023 and beyond there has been a complete decoupling, with veterinary prices increasing roughly 2-3x the official consumer price index (CPI). For comparison, veterinary price increases prior to 2020 averaged about 4% annually, a bit above inflation, but not multiples.

As you can see in the graph above, vetmed quickly overshot the mark on indexing to higher costs and didn’t look back. And some folks in the profession can be surprisingly cavalier about these price hikes, such as practice management consultant Darren Osborne (not a veterinarian), who wrote in a 2021 Canadian Vet Journal Op-Ed titled “Blame the pandemic: Why you need to raise your fees for 2021”:

If the looming surge in hospital expenses, combined with the readiness of clients to spend more on their pets isn’t enough to motivate an increase in fees, take solace in the notion that when fees are increased by 10%, the margin is boosted and a 25% loss in clients can be afforded while keeping the net income consistent.

Charging premium prices to fewer and fewer people is literally the definition of a luxury good! That strategy may be fine for non-essential products like sports cars and high-end clothing, but is that really the direction we want to take for healthcare? Do we want pets and vet care to be only for the affluent few, synonymous with status symbols like Birkin bags in the near future???

Even if you are fine with a luxury-esque approach, the assumption that the market will continue to bear these costs may no longer hold. As the figure from VetSource below indicates, we’re seeing diminishing returns: practice revenue consistently grew less than price increases in 2022 and 2023 due to fewer unique patients and declining visits overall.

Data from the large diagnostic lab company IDEXX tell a similar story: since 2022, practice revenue has increased 2% to 7% / year despite flat to negative visits. The biggest drop in visits has come from wellness appointments, which risks delaying care for diseases until they are more advanced and difficult (and expensive!) to treat.

Warning Signs Ahead

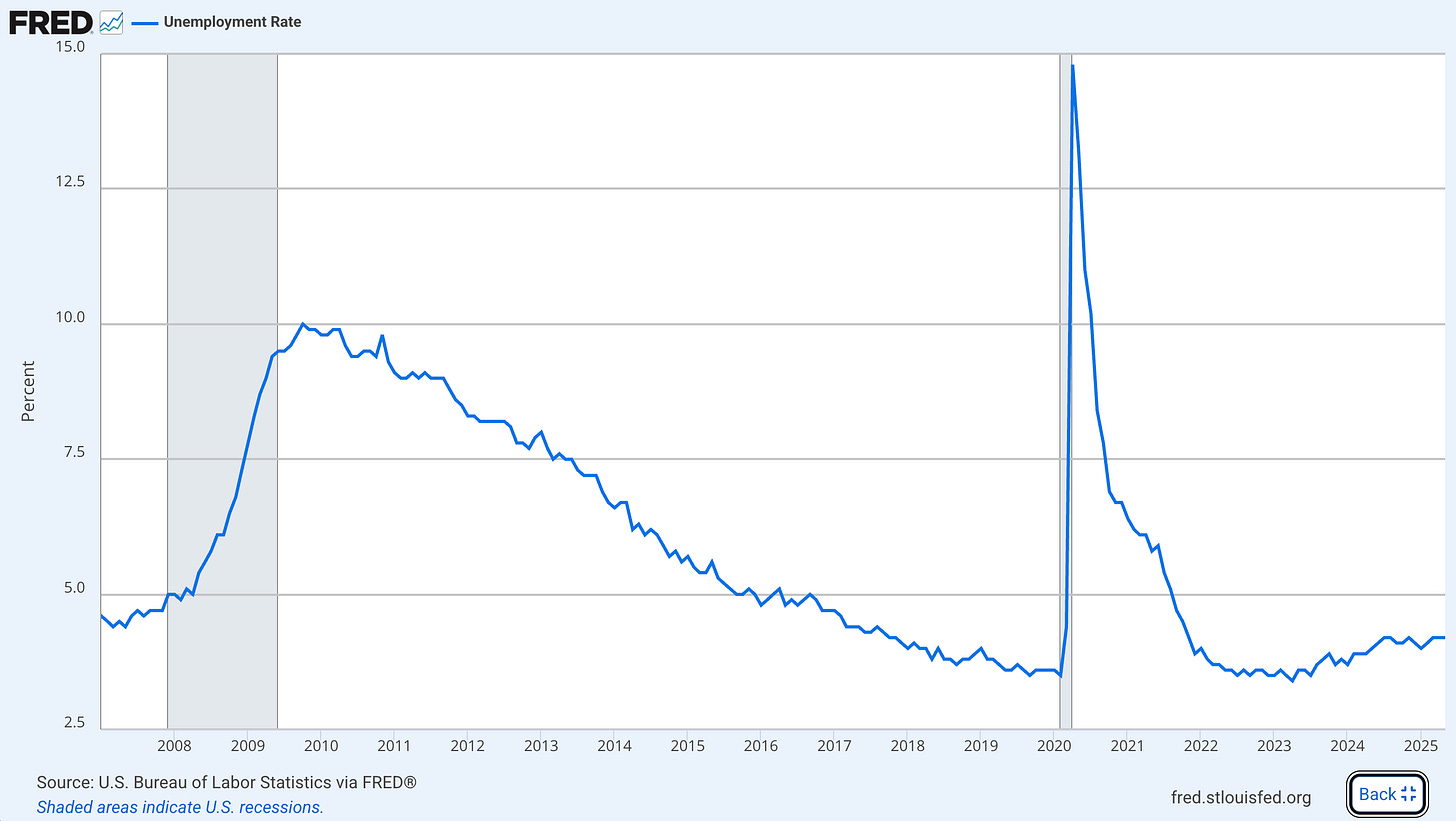

How long can this continue before something breaks? Not long, I fear. Practice revenues during the height of the 2008-2009 Great Recession grew at about 1.4% a year. In 2025, we’re hovering around 2%. Let’s pause to emphasize:

We are seeing similar numbers to the last major financial crisis in spite of solid GDP growth and a strong labor market!

Despite claims that veterinary medicine has inelastic demand, it is highly likely current price levels are already a drag on visits and revenue, and we have little to no margin of error in the event of economic headwinds. How will we be able to weather a recession or coming supply shocks like tariffs (that actually do require raising prices)?? When we have spent years charging more just because we can, we may find we priced out most of our customers when times really get tough.

In my opinion, these economic trends are a flashing yellow warning light. Continuing to raise prices substantially above inflation will hurt veterinary medicine in the long run. Seeing fewer patients undermines our veterinary oath, and it will damage the trust and credibility our profession has built over decades. We risk pet owners turning to alternative medicine and un-credentialed grifters to save money.

Even in terms of cold hard cash, there is an increasing risk this will backfire. Just ask how it turned out for those luxury goods companies I mentioned at the top:

From the McKinsey report:

As a result of these strategic choices and economic headwinds, growth in the years ahead will be slower. We expect global luxury sales to expand between 2 and 4 percent annually from 2025 to 2027, recovering modestly from 0 to 2 percent year-on-year growth in 2024. […] With sector recovery out of reach until late 2025 or 2026, the industry must use the slowdown as an opportunity to reflect and recalibrate. Luxury leaders must play a long game rather than relying on quick fixes to their most pressing challenges.

I couldn’t agree more with that last sentence! Individual veterinarians and technicians aren’t the ones setting these prices, and most of us feel terrible when we have to turn away or euthanize pets because their owners can’t afford the cost of medical care. It is incumbent on the practice owners and executives who run large hospital groups to take a step back and think about a more sustainable pricing strategy. This might anger shareholders over lower growth and profits in the short-term, but the goal should be ensuring a viable industry for decades to come.

—Eric

Hi, Eric. I live in a Caribbean country where veterinary care is much lower cost, but because on average people are much poorer in the Caribbean region, pet care can still be out of reach for many people. From this experience, I'd like to add a potential social cost of luxury pricing for veterinary care to your observations.

People who live in the USA, and then travel to the Caribbean (and other poorer countries, including India) will immediately notice the large number of stray dogs and cats (and occasionally other animals, like donkeys or goats, as well.) So for instance, if you take a romantic walk down a white-sand beach on St. Martin, you're sure to see a fair number of loose dogs. Most of these stray dogs are malnourished, and some are violent. It's a real threat to public tranquility and safety. I have heard tourists complain about "irresponsible pet ownership," but that's not a complete explanation for why there are so many wandering cats and dogs. The reason why there are so many strays in the Caribbean is because so few animals are spayed/neutered. The key reasons for that are lax enforcement of rules regarding neutering animals, and people being too poor to have their pets neutered.

Some islands (like mine, I am happy to say) heavily subsidize neutering animals and offer other incentives to do so, making the problem of strays much less severe. But most don't, and that's why there are so many strays on the beaches, and that's why that romantic barefoot walk on the beach may well give you ground itch. (A lot of the strays have worm infestations, too, needless to say.)

On the upside, at least on islands populations are isolated. So not only do you get to see cool genetic bottlenecking effects like lots of polydactyly, but also an island that's rabies-free (as many Caribbean islands are) remains rabies-free, even if there are a lot of stray dogs wandering about. In mainland places with this problem of strays, you also have to worry that the wandering dogs might bite you and infect you with rabies. This is one of the key reasons why about 50,000 people die of rabies every year in India, and almost all of those deaths are tied to dog bites.

Pet ownership is a human universal, across virtually all human cultures. People who can't afford veterinary care don't just decide to not have pets; after all, humans were turning wild animals into domestic companions far earlier than we had medicine of any kind. What they do is have pets, and care for them the best they can given their circumstances--care which may not include prevention.

If increasing veterinary care costs in general also radically increases the cost of preventive care like neutering and vaccinations, I fear that the United States could also face the problem of strays, and possibly even a return of rabies. And that's a problem that everyone pays for, whether or not they own a dog.

Oh wow. I have so much I could say. This took me back to a piece I wrote in May 2020. All the red flags about affordability were obvious then; and in fact, there was published data going as far back as 2007 (Jason B Coe, Ontario Veterinary Medical College) and the Bayer Veterinary Care Usage Study (2011) showing that pet owners were expressing concerns about the cost of veterinary care all those years ago.

Seemingly, no one in the profession really wanted to listen? To this day I’m not sure why.

Your piece today prompted me to go back and reread what I wrote in 2020 when we were still in the early throes of the pandemic.

The focus of what I wrote was less about prices than it was about urging vets to consider adopting accessible financing options other than the “old standby,” CareCredit, and to consider creative ways to help clients better manage costs (pay-in-advance plans, pay-as-you-go, things that dentists and cosmetic surgeons had already been doing for years.)

Anyway, I hear you. But as a pet owner who founded a company based on offering alternative payment options, for many years I had zero credibility with vets. I’m not sure why that was, seeing as I represent the people vets serve every single day — clients.

Nevertheless, maybe it was just a case of being too early with the message. The market, the profession, just hadn’t gotten there yet.

If you want to read my piece from 2020, I’ll include the link at the end of my comment. And if you visit my LinkedIn profile and look through my articles, I’ve been addressing this topic for a long time.

At least my mom read what I wrote, lol 😂

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-arent-more-veterinary-practices-talking-helping-cannon-ms-ma?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_ios&utm_campaign=share_via

And here is the link to the paper by Coe et al, published in 2007 in JAVMA, “A focus group study of veterinarians' and pet owners' perceptions of the monetary aspects of veterinary care.”

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18020992/