Weekend Roundup: Cancer Misdiagnosis & Overdiagnosis

Exploring uncertainties in oncology diagnostics

After being off-cycle for several weeks due to a very dense summer travel and locum schedule, we’re back with a regular Weekend Roundup. For this issue, I will be discussing several recent articles that deal with the gray areas in cancer diagnosis: How often is a patient told they have cancer when they actually don’t? How do patients navigate the ambiguity of being told they have a form of cancer, but it is not an immediate problem? When we are performing early screening for cancer, are we actually saving lives?

Are You Sure You Have Cancer?

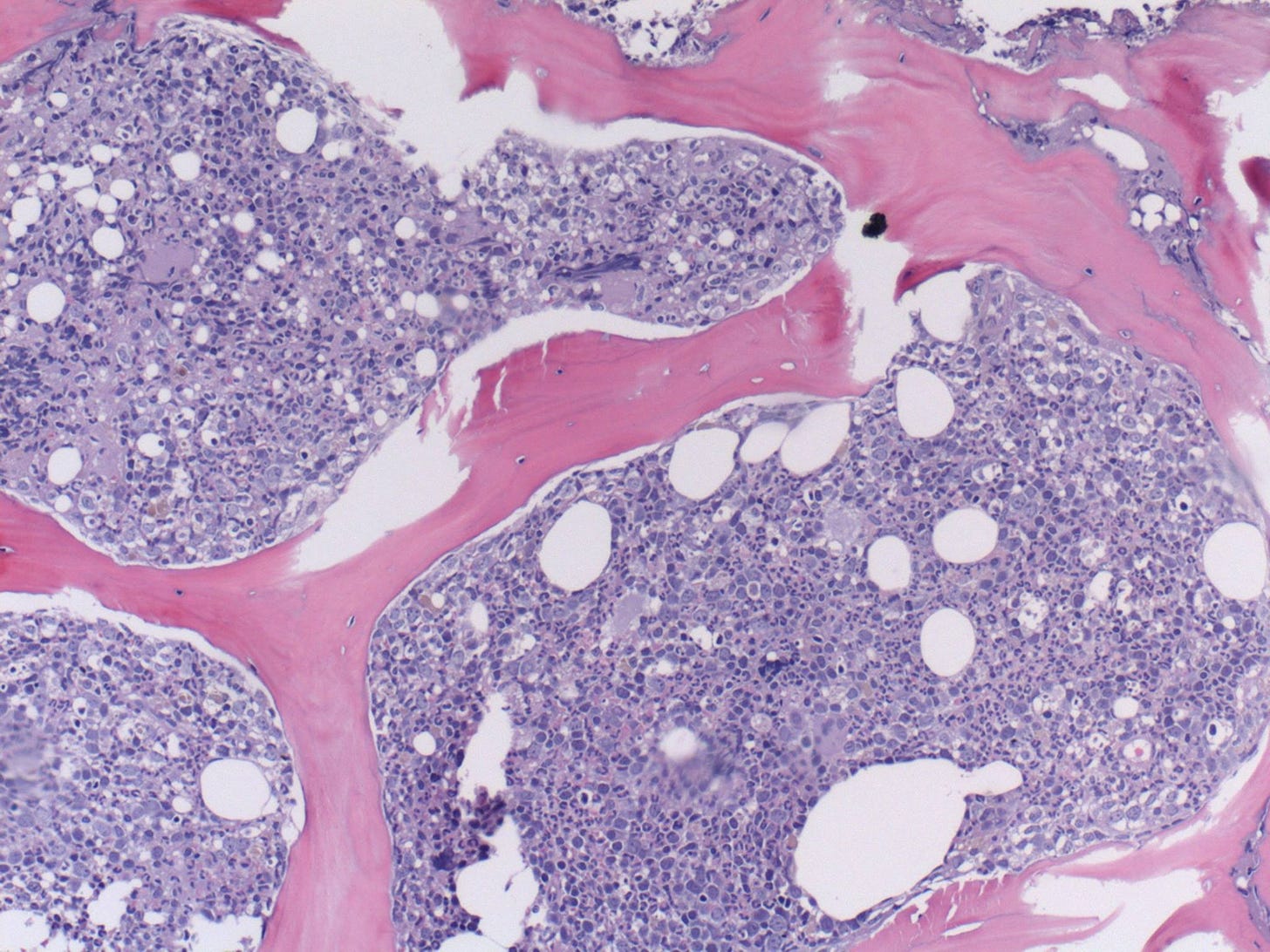

Cancer diagnosis is a critical aspect of oncology, as it serves as the foundation for treatment decisions and patient outcomes. Biopsy, the gold standard for diagnosing cancer, involves the removal and examination of tissue samples for the presence of malignant cells. As much as we want to believe our doctors are perfect, pathologists are only human, and microscopic samples come with intricacies and challenges that can lead to misdiagnosis, over-diagnosis, and under-diagnosis.

One oncologist recently wrote about this delicate issue in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece:

“How often do mistakes in diagnoses happen? I lead a study conducted through the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the National Cancer Institute, in which we are collecting clinical information and bone-marrow samples from 2,000 people who had abnormal blood counts and a suspected diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome. They were enrolled from over 140 cancer centers around the U.S. We compared the diagnoses at local cancer centers with those of pathologists who have expertise in myelodysplastic syndrome and leukemia and reviewed the same bone-marrow specimens.

The results were surprising. Expert pathologists agreed with the diagnoses of local doctors only 80% of the time. That means 1 in 5 patients may have been told that they had cancer when they didn’t, that they had a different cancer from the one growing in their bone marrow, or that they were cancer-free when they weren’t… Three of us who specialize in myelodysplastic syndrome and leukemia reviewed the treatments given to patients at their local cancer center and discovered something even more disturbing: About 7% of patients who received the wrong diagnosis also received the wrong therapy. Some were undertreated, while others were given chemotherapy without a verified cancer diagnosis.”

This is disturbing stuff! One of the take home points in this study is that medicine has become so complex that most doctors specialize or sub-specialize and develop expertise in one tiny niche. Pathologists are no longer jack-of-all-trades who evaluate any tissue under the microscope: Not only do some specialize in hematopathology (experts in blood diseases), but some go farther and become experts in one specific type of disease, say leukemia.

This means that at any given point, the person looking at your biopsy may not be the most knowledgable on the exact problem you have. In a perfect world, every specimen would be read out by the absolute expert in that specific area. Unfortunately, there are too few pathologists in general, to say nothing of those subspecialists, and with millions of patient biopsies a year, some amount of triage is necessary.

What lessons should we take away from this? The authors of that study above concluded:

“Misdiagnoses of patients with suspected MDS occurred at an appreciable rate, as did miscoding errors of MDS diagnoses, and this resulted in mistreatment of patients a minority of the time.”

“The accuracy of MDS diagnoses and prognosis can be dependent upon strong collaboration between clinicians and skilled pathologists.”

“Patients or medical providers who seek second opinion diagnoses may be critical to limiting the frequency at which misinformation is given and improve the course of recommended therapy.”

As is often the case, the key is good communication between the patient and their care team. So if you have any questions or doubts about your diagnosis, don’t stay quiet, make sure to raise them with your healthcare providers!

Not Everything We Call Cancer Should Be Called Cancer

A different issue than straight up misdiagnosis is when your biopsy result is technically cancer at the microscopic level, but is not anywhere close to the aggressive terminal disease we normally think of. This distinction can be hard to grasp for patients, lead to unnecessary worry, and can result in aggressive treatment that may not be needed. Two cancer surgeons argue persuasively in this New York Times op-ed for a shift in management approaches to these diseases:

“Let’s look at two examples. For prostate cancer, a biopsy showing a grade of Gleason 6 (also known as Grade Group 1) is considered low or very low risk. In breast cancer, diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ, or D.C.I.S., is similarly low or very low risk, indicating the very earliest, noninvasive stage of the disease.

These findings make up about 20 percent to 25 percent of prostate and breast cancer diagnoses in the United States, involving about 100,000 people annually. These patients are routinely treated with surgery or radiation, even though their conditions are not life threatening and cause no symptoms at the time they are spotted. To our knowledge, neither Gleason 6 nor D.C.I.S. spreads to other parts of the body unless more aggressive forms of cancer develop or are simultaneously present. They are more accurately explained as risk factors for prostate or breast cancers with malignant potential…

Another approach is to monitor these very early-stage cancers in what’s known as active surveillance, in which the condition is watched closely for changes but not treated until necessary. This approach is now increasingly used for early-stage prostate cancer; in Sweden, for instance, about 90 percent of these patients are put on active surveillance. The United States lags, with only about 60 percent of patients following this protocol. A long-term study of 1,800 men with low- or very low-risk prostate cancer begun in 1995 found that within the first 10 years, 48 percent had switched to treatment, most commonly because of a change in their cancer. Nevertheless, after 15 years, the risk of metastasis or death from prostate cancer was 0.1 percent.”

They also advocate for changes in terminology that would make this clearer to patients:

“Renaming very low-risk cancers would make it easier to persuade patients when it’s appropriate to adopt monitoring and risk reduction as their approaches. Early-stage “cancers” that meet the microscopic definition of the disease (what a pathologist sees through the microscope) but not the clinical definition (a condition that is highly likely to grow and cause symptoms and has the potential to kill a person) could be designated as IDLE (indolent lesion of epithelial origin) or preneoplasia — anything but the dreaded C-word.

This has already been done for some types of thyroid, bladder, kidney, cervical and other cancers. After the diagnosis of cervical carcinoma in situ was changed to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, fewer women underwent unnecessary hysterectomies. These conditions are not emergencies. As with any breast and prostate cancers, there is time to learn and decide on the best approach, evaluate treatments if required or consider being part of a clinical study.”

Cancer is not one disease but many, and exists on a spectrum of severity. As we learn more about these conditions we must continue to shape the language around them so they are clear and facilitate the best decision-making.

Estimated Lifetime Gained With Cancer Screening Tests

One the core tenets of oncology and public health for the past several decades has been: EARLY SCREENING SAVES LIVES

The logic is perfectly intuitive: If you catch a tumor when it's small and can be removed or easily treated with a lower dose of radiation or chemotherapy, it should lead to more cures and better outcomes. But does it?

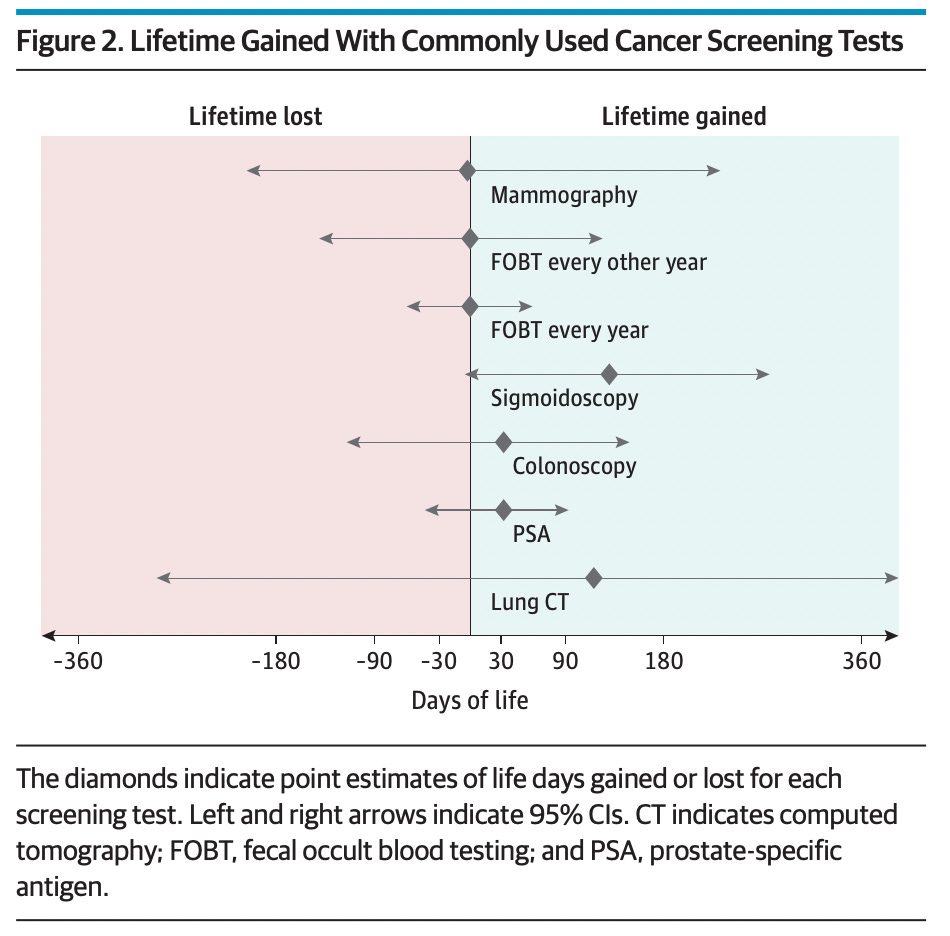

Doctors and scientists have been gathering data for years to see if early screening makes a difference in the real world, and the answer is far from certain. One recent systematic review evaluated 18 long-term clinical trials and found that most do not have a significant benefit. From the article summary:

Question Cancer screening tests are promoted to save lives, but how much is life extended due to commonly used cancer screening tests?

Findings In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 18 long-term randomized clinical trials involving 2.1 million individuals, colorectal cancer screening with sigmoidoscopy prolonged lifetime by 110 days, while fecal testing and mammography screening did not prolong life. An extension of 37 days was noted for prostate cancer screening with prostate-specific antigen testing and 107 days with lung cancer screening using computed tomography, but estimates are uncertain.

Meaning The findings of this meta-analysis suggest that colorectal cancer screening with sigmoidoscopy may extend life by approximately 3 months; lifetime gain for other screening tests appears to be unlikely or uncertain.

How could this be the case? One possibility is that catching cancers earlier simply doesn’t impact the course of the disease compared to later diagnosis for the majority of patients. Second, like the previous article discussed, it is possible that most of the additional cancers we’re catching early are those marginal lesions that are not clinically meaningful, while the more aggressive types continue to be detected too late. Finally, no medical interventions are free from side effects, and it is possible that the negative impacts of chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery (and necessarily anesthesia) mitigate the benefits for some of these tumors.

The authors of this study are careful to explain the difference between individual cases where early screening indeed helps them live longer, compared to the overall population averages where that may not be the case:

“Even if we did not observe longer lives in general with 5 of the 6 screening tests, some individuals prolong their life due to these screening tests. Cancer is prevented or detected in an early stage, and the individuals survive screening and subse- quent treatment without harms or complications. Without screening, these patients may have died of cancer because it would have been detected at a later, incurable stage. Thus, these patients experience a gain in lifetime.

However, other individuals experience a lifetime loss due to screening. This loss is caused by harms associated with screening or with treatment of screening-detected cancers, for example, due to colon perforation during colonoscopy or myocardial infarction following radical prostatectomy.”

This is not to say we should abandon early screening, only that we need to rigorously test the cost/benefit value of each potential intervention to make sure we are doing the best for patients. This is even more critical as we move from traditional, well-studied tests like mammograms and colonoscopy to sensitive novel molecular cancer tests of uncertain accuracy.

I hope this article shows how the intricacies and challenges of cancer testing are complex and multifaceted. These diagnostic pitfalls can have profound consequences for patient care and outcomes. To address these challenges, ongoing research, developing standardized diagnostic criteria, and an interdisciplinary approach involving clinical correlation with screening and diagnostic test results are critical to help mitigate these risks. Ultimately, the goal of everyone involved is the same—to provide patients with the most accurate and timely diagnoses to guide appropriate treatment decisions and improve their chances of survival and quality of life.

I haven’t had any of the examples you give above, but have wrestled with the pervasive advice to get mammograms on the regular, and what seems to be no evidence that they are indicated if you don’t have a family history . . . Figure 2 above is interesting to say the least!