Dear Readers,

Following up my recent post about the Laws of Pathology, I wanted to share a quick story with you that vividly illustrates some of those points. Several years ago, I had a memorable end of the day STAT case that was literally a matter of life and death.

It was around 5 pm, but there was still a stack of cases to work through. Getting a STAT while you’re trying to finish up and go home is the last thing any pathologist wants, but sometimes the situation warrants it. This sample from was a middle-aged Golden Retriever named “Max” (not his real name) coming in through oncology. Max had a prior history of multicentric large cell lymphoma that was treated with standard chemotherapy. He had responded well and gone into remission. That is, until today.

His lymph nodes were enlarged and he had a mild fever. He was lethargic and wouldn’t eat. He walked gingerly, like it hurt to be alive.

The oncology team was understandably suspicious Max’s lymphoma had relapsed. If that was the case, the owners were not interested in trying a rescue protocol of more chemo or other treatments. They were ready to say goodbye and euthanize him. To their credit, his doctors wanted to verify their hunch first and aspirated the lymph nodes for confirmation.

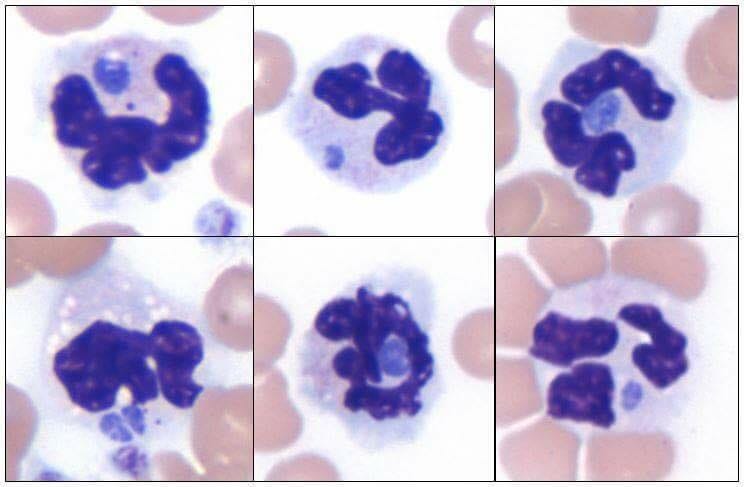

When I started looking at the slides under the microscope, a number of things were odd. First, the lymphocytes in his node were a mix of different sizes and appearances, along with numerous plasma cells that make antibodies. This is what benign reactive lymph nodes usually look like. In contrast, most dogs with lymphoma have nodes comprised of almost all large, immature lymphocytes with numerous mitotic figures indicating lots of rapidly dividing cancer cells. Second, there were lots of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell that often fights infections. Compare Max’s cytology to a classic lymphoma case below:

Something wasn’t adding up. While chemotherapy can change the appearance of the cells in a lymph node, and early relapse can be tricky to diagnose, I became increasingly suspicious Max did not have lymphoma.

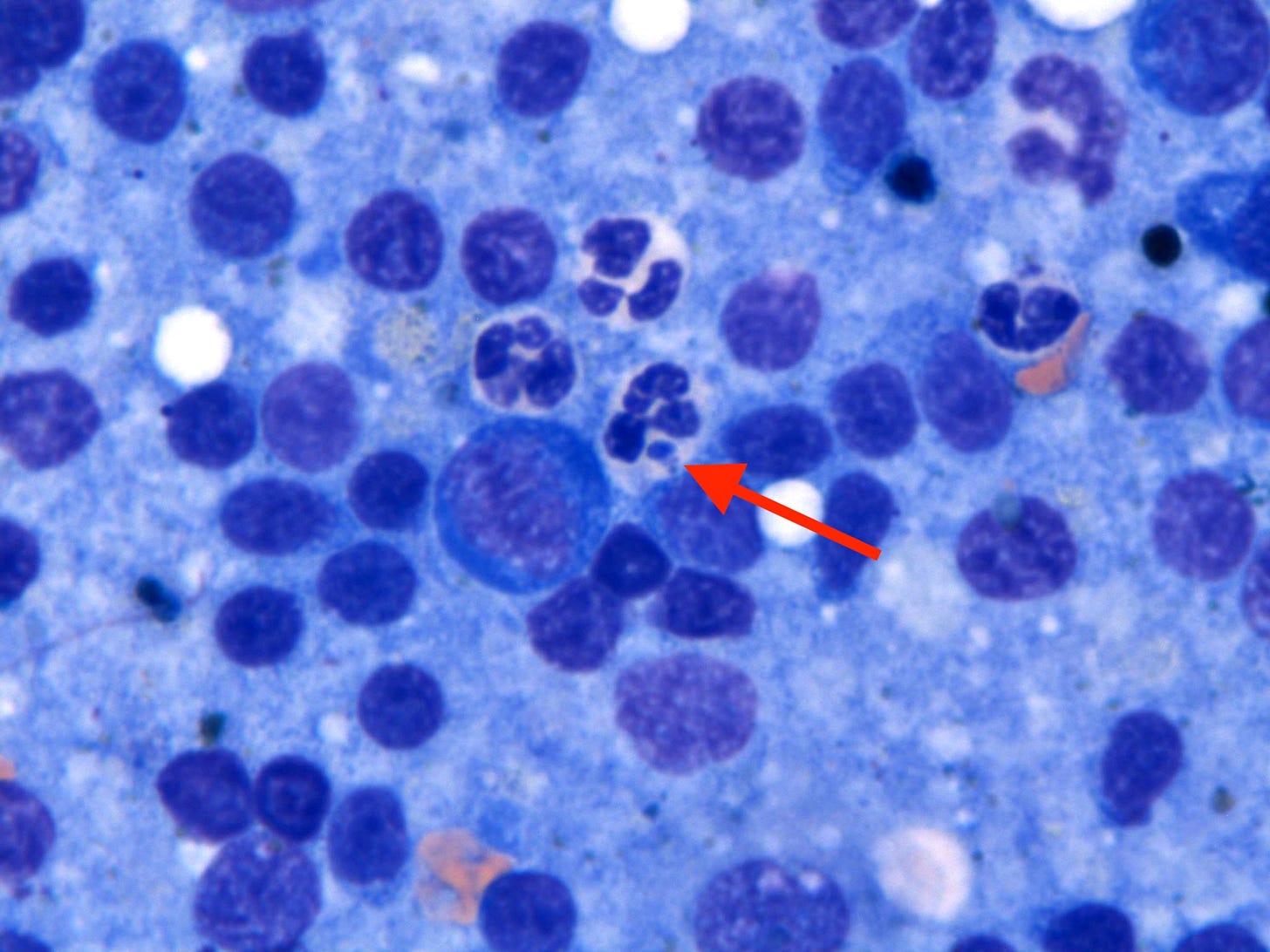

As I looked around, I noticed a number of the neutrophils had these weird, chunky, blue-gray structures inside them:

The first one I saw, I wrote off as non-specific junk. But as I noticed more and more structures like those, I couldn’t shake the feeling that they were significant. At higher magnification, they had a complex granular structure reminiscent of morulae, the packets of intracellular bacteria that many tick-borne illnesses create.

(As an interesting side note, the word “morula” comes from from the Latin root for blackberries, because the structure resembles the knobby fruit)

We usually identify morulae on blood smears, where they are the most frequent and easy to see. I actually hadn’t heard of a case being diagnosed in lymph node cytology before. I suddenly had a thought: did Max have recent bloodwork?

As luck would have it, he did! Max had baseline testing that day, including a Complete Blood Count (CBC). Nothing unusual was noted on it, but all of the key values like red cell, white cell, and platelet counts were normal, so it hadn’t been flagged for a pathologist review. I grabbed the slide and took a look…

All Science Great & Small is a reader-supported guide to veterinary medicine, science, and technology. Both free and paid subscriptions are available. If you want to support my work, the best way is by taking out a paid subscription 👇

They were rare, but in a handful of cells, nearly identical structures could be seen:

This confirmed they were indeed morulae from a tick borne infection! Based on the appearance and types of cells they were inside, it was most likely a type of Anaplasma or Ehrlichia. Like Lyme Disease, these bugs often cause fever, swollen lymph nodes, and can cause inflammation throughout the body, including arthritis in multiple joints.

This diagnosis changed everything, from a terminal cancer relapse to an easily treatable disease. However, Max was going to be put to sleep any minute and I needed to make the doctor aware.

I tried calling their phone.

No response.

I got up and ran across the hospital to the oncology ward, hoping I wasn’t too late.

Fortunately, I was able intercept Max’s doctor and breathlessly told them the news. They were pleasantly surprised and decided to treat the infection to see if Max improved. He was started on an antibiotic (doxycycline) that evening.

By morning, his fever had broken and he was eating.

He had responded as expected. Follow-up serology testing confirmed Max had been infected with Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Feeling better, he was discharged that day. Most dogs with Anaplasmosis who follow the standard treatment recommendations fully recover and clear the infection. Then again, most don’t also have slumbering cancer cells hiding in their body…

We had saved Max from euthanasia and bought him some time. This was a win in the short term, although on a long enough timeline, the odds were high that Max’s lymphoma would eventually return and claim his life. You may find any celebration for delaying the inevitable strange, yet the focus of veterinary oncology is on quality of life rather than length itself. Survival times for dogs with cancer are much shorter than in people, often measured in months, rather than years. Any amount of extra time is precious as long as the animal is comfortable and happy. I’m reminded of this scene from the medical dramedy Scrubs, where Dr. Cox explains to his young protege this fundamental truth about medicine:

Max’s case reminds me of many of the lessons I’ve learned as a pathologist over the past decade:

“Never make a cellular diagnosis without looking at a cell”

and

“The craziest cases come in at the end of the day”

This was also the rare case where the exception proves the rule:

“The more excited the pathologist, the worse the prognosis”

Finally, it even touches on the need to cultivate solitude and patience that I wrote about last summer in my article Letters to a Young Pathologist:

“Finding a single tiny bug in a lesion can make the difference between survival and death... Cultivating the ability to slowly comb through samples for those close catches requires a zen-like patience. It is not easy, but it can be learned through practice, often in solitude.”

Max was lost to follow-up, and I don’t know how his story ended. I choose to believe his family enjoyed many extra days of walks, wags, and treats as a result of multiple people on his care team doing their best to leave no stone unturned, rather than play the odds and assume his time was up.

The owners got to take him home.

If they're like most owners I know, they are exceedingly grateful for that reprieve.

Great work!

Yay! And as a note...is Anaplasmosis increasing everywhere? We have weekly positives on snap tests now, very few are sick or PCR positive.