February Avian Influenza (H5N1) Round-Up

Updates on "bird flu" in cats, monkeys, and veterinarians

Dear Readers,

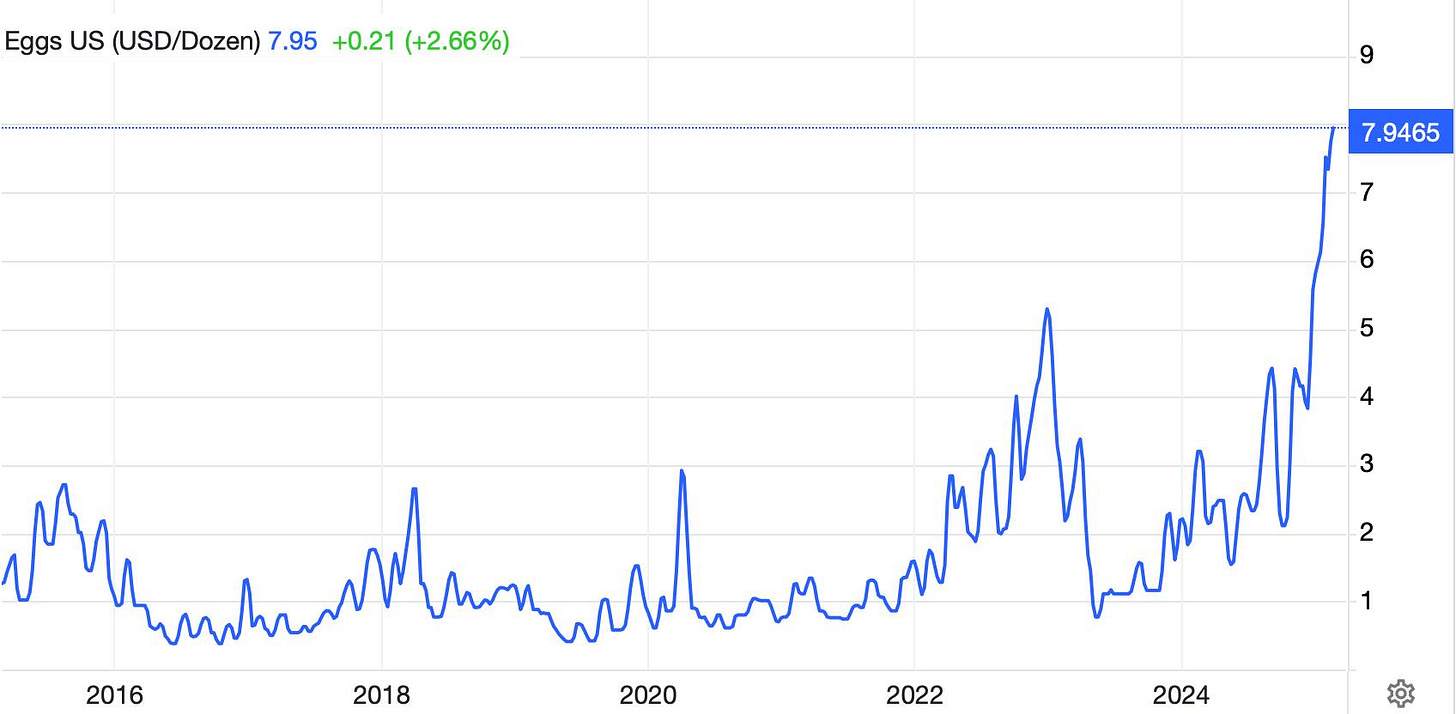

Amid the flurry of government and political news over the past two months, there has been a steady trickle of updates quietly coming out about avian influenza H5N1. People may understandably want to move on from respiratory pandemics after COVID, but viruses don’t care about our feelings. Indeed, avian influenza has resulted in millions of bird deaths over the past two years, which is the primary driver of high egg prices:

Today I will discuss three newer reports about H5N1 in cats, monkeys, and dairy vets. Please let me know what questions you have about bird flu so I can make sure to include answers in the comments and/or future posts.

—Eric

H5N1 serology in vets shows subclinical spread

Last Thursday, the CDC published a study looking at H5N1 antibodies in bovine vets in their Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). The study population was 150 large animal veterinarians who had worked with cattle over the past three months, and they were recruited from a veterinary conference. Practitioners were from 46 states in the US and seven provinces in Canada. Three of them (2%)—all from the US—were positive for antibodies to Influenza A-H5, providing evidence of recent exposure to bird flu. None reported any respiratory signs or symptoms of flu-like illness, and none had been tested for the flu since January 2024. They wore basic PPE like gloves during procedures and animal handling, but not masks or goggles/face shields.

These vets worked with multiple species, including dairy and non-dairy (likely beef) cattle, poultry, and in a multispecies livestock market. However, none had been working with cattle herds that had known or suspected H5N1 infections (one of the positive vets did work with a poultry flock that was positive for Influenza A-H5). Four of the states these vets worked in have not previously reported bird flu in any herds:

Taking a step back, it is not that surprising that there was a 2% seroprevalence of H5 in this population. A similar study of farm workers published last November showed a 7% positivity rate. So what does this report add that we didn’t previously know? First, this looks at veterinarians, whereas the previous report only looked at a convenience sample of farm workers. These populations have different roles and could have varying level of exposure. For example, someone who milks cows or cleans their pens all day would have a theoretically higher risk of exposure than a large animal veterinarian doing a quick pregnancy check exam. Furthermore, those farm workers came from two states that had already documented H5N1 infected herds (Colorado and Michigan). Lastly, there was a difference in disease severity, as 40% of those positive in the November study had at least mild symptoms, while all of the DVMs in the new report were apparently subclinically infected. This could possibly reflect differences in viral loads between the two groups.

I have several take-home points from this study. It suggests that H5N1 is even more widespread than we already knew. And it suggests that a population with at least theoretically lower risk of exposure is also getting infected. Since none were wearing masks or face/eye protection, it might be worth vets working with these species upgrading their PPE protocols while the H5N1 outbreak is ongoing.

Cats are vulnerable to H5N1, can pass it to people

Another recent story in the H5N1 outbreak is that cats—both domestic and large cats like leopards, mountain lions and bobcats—are highly susceptible to the virus. Cats with avian influenza often develop neurological signs, and many have died. Last year, the vast majority of those infected were barn and feral cats on dairy farms who were exposed to H5N1 through drinking milk.

Recently, there have been multiple reports that indoor-only pet cats have been sick with avian influenza. The source from several cats in Oregon and California appears to be commercial raw food diets (the protein in these was often turkey or chicken). Brands implicated so far have included:

Monarch Raw Pet Food

Northwest Naturals

Wild Coast Raw

Please note that this list is just what I could find from public health alerts, it may not be comprehensive or up-to-date as there is a lag between suspected cases, investigation, and publication. I would argue that you should avoid raw food in your pets anyway as there is little to no evidence of benefit and a large risk of foodborne illness—beyond H5N1, raw diets have been linked to E. coli, Listeria, and other pathogens. Pasteurization and cooking don’t hurt the nutritional content of food, they simply make it safer. If you still insist on feeding raw diets, I would definitely pass on the brands above and ideally avoid any made from poultry and beef protein. Monitor the web for recalls and report any signs of illness to your family vet.

Another new wrinkle to this story is the potential for infected pets to spread bird flu to their human owners. Per reporting from The New York Times:

Cats that became infected with bird flu might have spread the virus to humans in the same household and vice versa, according to data that briefly appeared online in a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention but then abruptly vanished. The data appear to have been mistakenly posted but includes crucial information about the risks of bird flu to people and pets.

In one household, an infected cat might have spread the virus to another cat and to a human adolescent, according to a copy of the data table obtained by The New York Times. The cat died four days after symptoms began. In a second household, an infected dairy farmworker appears to have been the first to show symptoms, and a cat then became ill two days later and died on the third day.

The infectious disease veterinarian Dr. J. Scott Weese has more scientific details about these cases at his Worms and Germs blog for those interested. Initially, the sudden withdrawal of this report by the MMWR raised concerns about censorship at the CDC. This is a reasonable fear given some of the diktats coming out of the new administration. However, sources inside these agencies told at Inside Medicine that the paper was posted online by mistake and that it needed more revision to withstand the intense scrutiny the agency is under. They have since published other reports on potentially sensitive topics like H5N1 and monkeypox, so I’m inclined to believe them.

UPDATE (2/21/25):

The previously posted and then un-posted CDC report on cats infected with bird flu is now officially published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Some relevant points from the paper’s Discussion section:

“Although reported cases of infection of indoor cats with HPAI A(H5N1) viruses are rare, such cats might pose a risk for human infection. The source of HPAI A(H5N1) virus infection in these two cats is unknown; however, the cats’ owners worked on dairy farms and potentially had occupational exposures to HPAI A(H5N1)–positive dairy cattle or contaminated products or environments. Further research is necessary to evaluate the risk of fomite transmission and other types of transmission routes of HPAI A(H5N1) virus to cats. The two dairy workers described in this report did not use recommended PPE before their illnesses and could have been exposed to HPAI A(H5N1) virus. However, because neither dairy worker received testing for A(H5), whether cat 1A’s owner’s gastrointestinal symptoms or cat 2A’s owner’s ocular symptoms were because of HPAI A(H5N1) virus infection or a different etiology is unknown.

Given the potential for fomite contamination, farmworkers are encouraged to consider removing clothing and footwear and to rinse off any animal byproduct residue (including milk and feces) before entering households. Veterinarians evaluating companion cats with signs of respiratory or neurologic illness in areas with HPAI A(H5N1) virus circulating in cattle or poultry or other animals are recommended to wear PPE when examining these animals or collecting specimens for influenza testing and to obtain occupational information from household members to help prevent unprotected exposures and guide coordinated One Health (i.e., human, animal, and environmental) public health investigations of potential animal-to-human spread of HPAI A(H5N1) virus. Implementation of standard precautions for zoonotic disease prevention and CDC guidance for veterinarians at veterinary clinics can help limit the number of staff members exposed to sick animals potentially infected with pathogens, including HPAI A(H5N1) virus. Further, given the widespread outbreak in animals, including poultry and wild birds, throughout the United States, anyone who has occupational or recreational exposure should wear the recommended PPE when interacting with any potentially infected animals.”

H5N1 pathogenicity may vary by route of exposure (at least in primates)

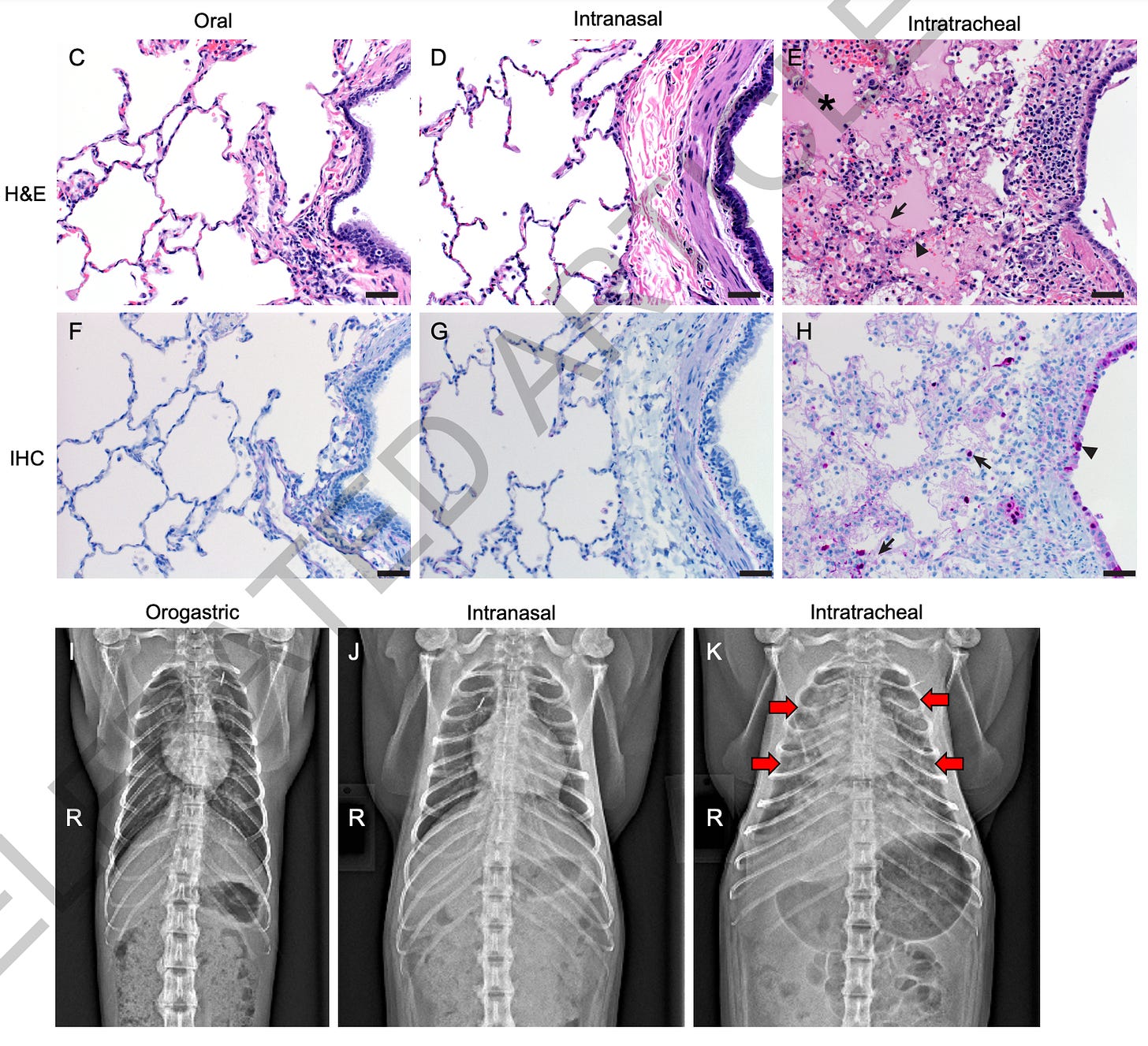

Finally, a new study on influenza H5N1 in primates from the NIH Rocky Mountain Laboratory was published in Nature a few weeks ago. While this manuscript passed peer review, it had not finished typesetting or final production, but the journal decided to release it early due to the time-sensitive nature of the work. Their paper, “Pathogenesis of bovine H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b infection in Macaques,” examined how the strain of H5N1 circulating in dairy cows affects cynomolgus macaques, serving as a stand-in for human infection risk. They inoculated the animals via three routes—intratracheal, intranasal, and orogastric—to reflect different real-world exposure scenarios. All macaques showed some degree of virus presence, but disease outcomes varied widely depending on the route of infection.

Notably, the macaques exposed through the intratracheal route, which targets the lower respiratory tract, developed the most severe respiratory disease, displaying widespread pneumonia and reaching humane endpoint criteria for euthanasia within a week. The intranasal route caused milder, self-limiting infections, with moderate shedding and mild lung lesions, whereas the orogastric route—designed to mirror ingestion of raw or contaminated milk—resulted in mostly subclinical disease. Even though virus replication did occur in orogastrically inoculated macaques, these animals experienced minimal symptoms and no significant respiratory pathology, highlighting how exposure route can determine both disease severity and transmissibility.

The findings underscore the importance of monitoring bovine H5N1 infections as a potential public health concern, especially considering ongoing reports of virus spread in poultry, wild birds, cattle, and other species. While raw milk contaminated with H5N1 can clearly infect primates, this study suggests that such exposure might not typically trigger severe illness. Keep in mind that the cats becoming severely ill from drinking infected milk shows this can vary by species, and monkeys are not a perfect model of human biology. Furthermore, this study looked at the version of bird flu currently circulating in dairy cattle, while the strain most prevalent in wild birds (D1.1) may be more deadly to humans as it was linked to the first H5N1 death in the US. This could also change as the virus mutates over time. Because of these reasons, the researchers emphasize that broader surveillance, safe milk pasteurization practices, and vigilant biosecurity measures remain critical to mitigating the risk of zoonotic spillover.

Thanks for this - I always look forward to your articles that explain things in ways I can understand.

https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/avian-influenza-bird-flu/canada-announces-avian-flu-vaccine-buy-usda-confirms-first-h5n1-detections