At 38, Anthony Bourdain was washed up. Despite a Culinary Institute of America pedigree, he’d spent his career as a chef in a haze of booze and drugs, bouncing around short-term gigs as a hired gun trying—and mostly failing—to turn around third-rate restaurants in New England. By the late-90s, he was working marginally more respectable chef jobs in Manhattan, but it was a far cry from his training and talent.

Unknown to most, Bourdain had long harbored ambitions of becoming a serious writer. He published his first novel, Bone in the Throat, in 1995, and his second, Gone Bamboo, in 1997. Unfortunately, both sold poorly and almost nobody read them. His writing career was dead on arrival.

In a bit of foreshadowing, in a 1997 interview for Gone Bamboo, The New York Times referred to him as the “Chef [who] Hopes To Write His Way Out of the Kitchen” and described his desire for a literary pivot:

Eventually, he'd like to give up both gangsters and chefs and move on. First to “my dream book, a definitive, foody memoir, a ribald account of my 22 years in the restaurant business that would probably appall and horrify anyone thinking of hiring me.” But by then it wouldn't matter. He'll be ready, he said, to burn his bridges in the restaurant business and become a full-time writer.

His fortunes changed virtually overnight when the New Yorker published his essay “Don’t Eat Before Reading This.”

It tore away the curtain separating diners from the kitchen and exposed the underbelly of an industry rife with roguish characters, shady business practices, and questionable food sanitation. Published in 1999, just before the dawn of the internet, social media, and “content” that goes “viral,” it was a runaway hit.

That essay quickly established Bourdain as the contrarian bad-boy of the restaurant world, a necessary tonic to the stodgy celebrity chefs popular at the time. Shortly after, he expanded that essay into the full-length book Kitchen Confidential—living up to his NYT interview dreams—and began a new career as a storyteller and media personality.

***

I will be 38 this summer. While it would be a stretch to draw too many comparisons between a veterinarian and a world-famous chef/traveler/raconteur, I feel like I’m at a similar cross-roads in my career as Bourdain was at Brasserie Les Halles. I’ve left clinical practice and three pathology jobs in five years. Every niche, from academia to start-ups to Big Corporate, presented problems I declared intractable and walked away from. Upon leaving my most recent job, I was branded with the scarlet letter “I”—an aggressive non-compete that, read literally, would prevent me from working in my field in almost any capacity.

As a result, I’m essentially “unemployed,” (self-employed is probably the more positive framing). So I bounce from gig to gig, teaching at various universities, doing short-term contracts, and writing a wonky newsletter with niche appeal for free. While I relish my freedom, it comes with a price. I’m on the road and away from my family for weeks and months at a time, living in an endless series of Air BNBs and hotels. I have to carefully budget my sporadic, “lumpy” income, made harder when some vendors are late or change terms. Some people have promised work only to ghost me. None of this should be taken as a “woe is me” pity party; we are in financially better shape than many people in this economy. Still, it takes a toll.

He'll be ready, he said, to burn his bridges in the restaurant business and become a full-time writer.

For my sanity, this all has to mean something, and I’m looking for opportunities to reinvent myself. Like Bourdain, I always wanted to be a writer. I was the precocious kid who had a subscription to Harper’s at 16 and read “On Writing” and “The Elements of Style” cover to cover. I’ve toiled at writing for years, submitting essays to various outlets and getting uniform rejection. My computers and cloud storage accounts are littered with aborted novel ideas. Perhaps this is my chance to take my writing more seriously, rather than as a secret hobby I half-ass.

Over the last 15 years, I’ve seen some truly wild stuff that I think would rival the most dysfunctional kitchens. Beautiful, bizarre, comical, heart-rending, profound, and disturbing things. I will never forget the near-miraculous recovery of Lazarus. I’ve had to convince New Age spiritualist owners that surgery is a better treatment for their ancient dachshund’s spinal problems than healing crystals and surfing. There was the dog with severe priapism and necrosis of his penis (think “if you have an erection lasting more than four hours, see a doctor”) that took me and another ER doctor hours to save his “manhood.” I once had to euthanize a seizing kitten via intracardiac injection on Christmas Eve while the owner casually asked “Is this going to take long? I’m missing dinner.” These are stories I can’t forget. They must be told, and now I have an outlet.

***

Anthony Bourdain died by suicide five years ago today. I remember seeing the news on my phone while I was at my 10 year college reunion in Ithaca. It was a gut punch that knocked the wind out of me. He was the first—and perhaps only—celebrity death that has moved me personally. But I don’t want to dwell on the circumstances of his death, that would be a disservice to his complex life and the lasting impact of his work.

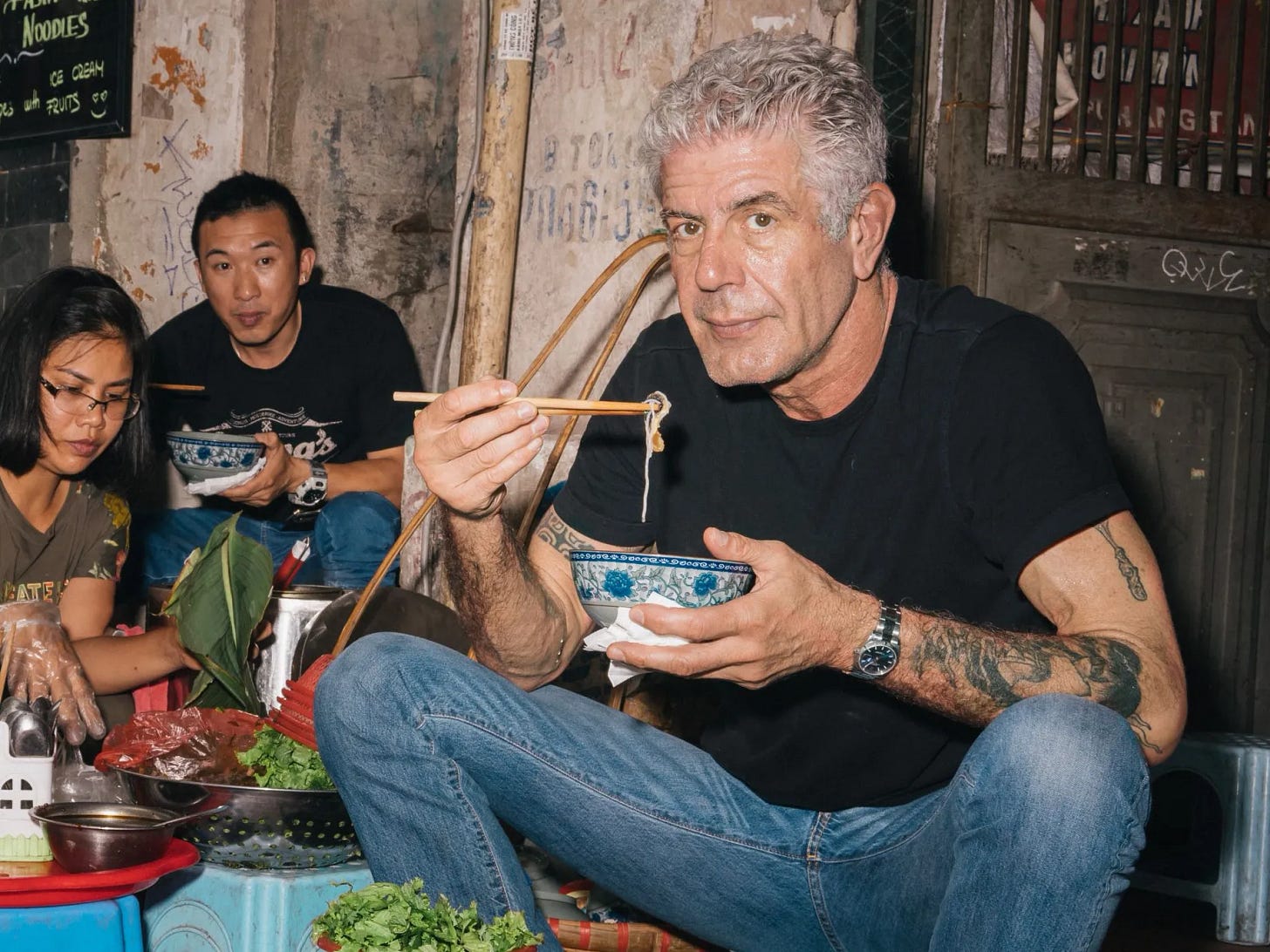

I read Kitchen Confidential senior year of vet school while living in a cramped 180 square foot apartment in a dicey part of downtown LA. His literary voice blew me away: The frank honesty and willingness to show the ugly parts of himself and reflect on his failures elevated his story above standard mediocre foodie narratives. After that, I became hooked on No Reservations (and later Parts Unknown). His gorgeously photographed world travels were a welcome escape from my transient, broke grad student existence. I appreciated his uncommon blend of cynicism, sarcasm, and profanity with his simultaneous curiosity and empathy for everyone he encountered. Bourdain’s work made a point to connect food to the history, politics, and struggles of the ordinary citizens of the places he visited.

As silly as it sounds to be influenced by someone you’ve never met, Anthony Bourdain inspired me to travel as widely as I could, to be more open to experiences and try food and drink I otherwise wouldn’t. He convinced me to be more adventurous, and less scared, than I was growing up. To be willing to have a bad meal, to get that weird tattoo, to do a bourbon luge, to see what was down that sketchy looking street. To take chances and see where life takes me.

And now, I take inspiration from his literary career and embark on my own writing journey. The silver lining to being independent is I’m free to write whatever the hell I want. For now, that is publishing medical narratives and science journalism on All Science Great & Small. I’m brainstorming ideas for a book. Who knows where it will lead?

In the end, the best tribute to Anthony Bourdain might be to say fuck heroes and role models, you have to chart your own course. Don’t be afraid to reinvent yourself. Life is short, so order the fois gras and some stinky cheese. Don’t ask Tripadvisor where to eat next time you’re in Paris, wander down an alley and find a plat du jour that looks interesting. Just get out there and explore, be open to the enormity of the world, and make sure to tell people about what you found along the way.

Great essay, Eric. I can relate to a lot of what you write--as someone who walked away from a solid job and am now floating a bit, I get it. Good luck with this next chapter, both figuratively and literally!

Wonderfully written essay. It made me think of my own trajectory, would-be stockbroker, would-be mathematics professor, then abd philosopher, then would-be lawyer, then ordained monk, then returned to lay life and at age 38 working at a bookstore, about to meet the love of my life, return to academia and make the biggest contributions of my life, small as they were, to both science and education. And the bookstore was 37 years ago.

But what made all those endeavors possible was financial security- the scaffolding that supported all those billboards of career changes I put up. And now I am trying to give back: the final career change. There's a symmetry there somewhere.....

When young, we are the stars of the drama we are both writing and being written for us. When old, we no longer care a whit for ourselves, the drama has been written and read and shelved away,