As a veterinarian, I am a strong believer in the practice of medicine and its ability to improve peoples’ lives. You won’t catch me writing conspiratorial rants about how modern medicine and pharma is a scam or GOOP-style articles about how all we need to be healthy is just to take herbs or essential oils or focus our chakras or whatever nonsense. The vast majority of doctors, dentists, veterinarians, and other health professionals work extremely hard and want the best for their patients, and I believe most are not primarily motivated by money (clearly it plays some role, your plumber doesn’t work for free because he loves sewage!)

That said, it is unfortunately true that some people and animals have bad outcomes that could have been prevented. Sometimes this is an issue of knowledge gaps or incompetence. Rarely, it is from bad actors with malicious intent (see the end of this article). But more commonly, it is because our healthcare systems are complicated and fragmented, and a cascade of ambiguous study data, bad economic incentives and poorly-crafted policies lead to less optimal care when the gold standard is not clear.

For this Weekend Roundup, I will be focusing on problems not with medical malpractice per se, but the costs and harms resulting from excessive and unnecessary care.

Unnecessary Vascular Procedures Lead to Amputations

One of the stories that made me want to write about this topic was this shocking New York Times article about the explosive rise in atherectomy vascular procedures for people with peripheral artery disease (PAD). Atherectomy is a minimally invasive procedure to clear out sticky plaques in vessels to restore blood flow. This was originally pioneered in the 80s for coronary artery disease, and has seen surging popularity recently for PAD. While touted as a way for patients with PAD to avoid limb amputations, it may not help at all, and can actually increase the risk of losing a leg:

“Yet a wide body of scientific research has found that for about 90 percent of people with peripheral artery disease — including those who experience the most common symptom, pain while walking, or have no symptoms — the recommended treatments are blood-thinning medications and lifestyle changes like getting more exercise or quitting smoking.

For some people with advanced forms of peripheral artery disease, atherectomies can be useful. But even for them, studies have found that atherectomies do not work better than less expensive methods of clearing blockages and restoring blood flow. Others have found that because atherectomies can further inflame patients’ arteries, they can lead to higher rates of amputations. And atherectomies tend to beget more atherectomies.”

I have written previously about the importance of Evidence-Based Medicine (EMB) to rigorously evaluate the performance of tests and treatments in the medical profession. The gold-standard in EBM are systematic reviews—essentially massive scientific studies of all of the various research on a topic with transparency on their methods—and one of the most well-known and trusted sources are the Cochrane Reviews from an international non-profit focused on medical quality improvement. Here is what the Cochrane review on atherectomy for PAD found:

“Certainty of the evidence

Overall, our certainty in the evidence is very low, which means we do not have confidence that our results show the true effect of the treatments. We downgraded our certainty in the evidence because the studies were at high risk of bias (lack of blinding of participants or assessors, several outcomes were not reported and a number of the participants did not complete the studies); the trials were all small; and their results were inconsistent.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have found no clear difference in effect on patency, mortality or cardiovascular event rates when comparing atherectomy against balloon angioplasty with or without stenting. The limited evidence available does not support a significant advantage of atherectomy over conventional balloon angioplasty or stenting.”

If this procedure does not appear to provide any advantages against the previous standard of care, and may actually increase some risks, why have they surged in popularity? You can probably guess—it’s about the money. From the NYT article:

“There are two reasons. First, the government changed how it pays doctors for these procedures. In 2008, Medicare created incentives for doctors to perform all sorts of procedures outside of hospitals, part of an effort to curb medical costs. A few years later, it began paying doctors for outpatient atherectomies, transforming the procedure into a surefire moneymaker. Doctors rushed to capitalize on the opportunity by opening their own outpatient clinics, where by 2021 they were billing $10,000 or more per atherectomy.

The second reason: Companies that make equipment for vascular procedures pumped resources into a fledgling field of medicine to build a lucrative market.

When doctors open their own vascular clinics, major players like Abbott Laboratories and Boston Scientific are there to help with training and billing tips. The electronics giant Philips works with a finance company to offer loans for equipment and dangles discounts to clinics that do more procedures… The device industry rewards high-volume doctors with lucrative consulting and teaching opportunities. And it sponsors medical conferences and academic journals to bolster a niche medical field that favors aggressive interventions.

This self-sustaining ecosystem is worth $2 billion a year, analysts estimate. Insurers pay doctors per procedure. And because new equipment is needed each time, the companies also profit from repeat customers.”

I am sure many of these doctors, and perhaps even the companies that created the devices, think that these procedures are helping patients. But the mind is a powerful thing, and it is easy to fall into such rationalizations and motivated reasoning when those choices result in a financial windfall. And it is also the case that sometimes innovative new drugs and devices that required massive R&D costs are simply no better than what we already had, yet people feel invested in selling them.

An “Epidemic” of Unnecessary Care

How prevalent are situations like atherectomy for PAD? You would hope that perhaps that is an unusual outlier and/or a recent problem. Unfortunately, low-value or no-value care appears to be extremely common and longstanding. The surgeon Dr. Atul Gawande wrote about this “epidemic” in a 2015 article for the New Yorker:

“The one that got me thinking, however, was a study of more than a million Medicare patients. It suggested that a huge proportion had received care that was simply a waste. The researchers called it “low-value care.” But, really, it was no-value care. They studied how often people received one of twenty-six tests or treatments that scientific and professional organizations have consistently determined to have no benefit or to be outright harmful. Their list included doing an EEG for an uncomplicated headache (EEGs are for diagnosing seizure disorders, not headaches), or doing a CT or MRI scan for low-back pain in patients without any signs of a neurological problem (studies consistently show that scanning such patients adds nothing except cost), or putting a coronary-artery stent in patients with stable cardiac disease (the likelihood of a heart attack or death after five years is unaffected by the stent). In just a single year, the researchers reported, twenty-five to forty-two per cent of Medicare patients received at least one of the twenty-six useless tests and treatments.

Could pointless medical care really be that widespread? Six years ago, I wrote an article for this magazine, titled “The Cost Conundrum,” which explored the problem of unnecessary care in McAllen, Texas, a community with some of the highest per-capita costs for Medicare in the nation. But was McAllen an anomaly or did it represent an emerging norm? In 2010, the Institute of Medicine issued a report stating that waste accounted for thirty per cent of health-care spending, or some seven hundred and fifty billion dollars a year, which was more than our nation’s entire budget for K-12 education. The report found that higher prices, administrative expenses, and fraud accounted for almost half of this waste. Bigger than any of those, however, was the amount spent on unnecessary health-care services. Now a far more detailed study confirmed that such waste was pervasive.”

Some of the problem here is doctors—and veterinarians!—have a bias towards action. It is very difficult in practice to invert the conventional wisdom and “Don’t just do something, stand there” when a patient is ill or suffering, and this can lead to trying something, anything, that might help them. Ignoring or opting for careful monitoring of marginal test results risks liability; it is safer to CYA by ordering more tests for “peace of mind.” This is compounded by an increasing focus on patient satisfaction scores in doctor assessment and compensation. The doctor who just gives in and orders an MRI for a patient with chronic back pain is likely to get 5-star reviews and patients lauding their empathy, while a physician who declines the unnecessary test, no matter how gently, will often get angry pushback in person and online.

It is very difficult in practice to invert the conventional wisdom and “Don’t just do something, stand there” when a patient is ill or suffering, and this can lead to trying something, anything, that might help them.

Another problem is that people hate being told what to do, especially when it comes from the government, and definitely when it comes to being told you can’t have something because it's too expensive. This reared its head during the Affordable Care Act debates with the incorrect and disparaging label of “death panels” for the concept of an outside body that would perform cost-benefit analysis on medical interventions. From an interview with Dr. Milton Weinstein at the Harvard School of Public Health:

Q: Why did so many people equate cost containment in health care, and assessing the costs and benefits of medical technology, with “death panels”?

A: Because we don’t like to have government—we don’t like to have anybody—make decisions for us. We don’t mind using markets to ration things. If the price of a bottle of wine is too high, then we’ll buy a different bottle of wine. But if a big sign says the U.S. Department of Agriculture has determined that you can’t have prime rib because it’s too expensive, people don’t like it.

Q: What’s at stake if we don’t have a national discussion about the costs of medical technology?

A: Costs will keep going up. People will keep demanding costly new procedures. More and more people will have inadequate care. From a public policy viewpoint, we could end up with more disparities in this country than we already have—which is the worst in the developed world.

Q: In other words, rationing?

A: Yes. The biggest way we ration is by cutting people out of care. When 15 percent of people in this country have no health insurance, that’s rationing.

Q: Why can’t they talk about it?

A: People don’t want to think about it. They think they can have their cake and eat it too.

It’s amazing how uninformed people are. “I want the best available medical care regardless of cost”—90 percent of people agree with that. “I think that health care is too expensive”—90 percent of people agree with that. “I think health care should be available for everyone”—90 percent of people agree with that. You can’t have it all.

Private Equity is Taking Over Both Human and Veterinary Medicine

Another factor that contributes to excess care and increasing medical prices is a trend towards private equity (PE) involvement in human medicine. For those who aren’t familiar, private equity is simply a form of investment that is not publicly traded. PE differs from groups like angel investors and venture capital who tend to invest in early stage start-ups. They often take ownership stakes in companies that are struggling (and are thus usually underpriced) and try to turn them around. Often, this is funded by substantial debt that the acquired company takes on. PE firms can get a return on their investment (ROI) from a portion of the profits, but they commonly try to sell the companies for more than they initially paid (akin to “flipping” houses).

There is nothing inherently wrong with PE in and of itself. They will claim that they make necessary efficiencies in poorly-run businesses and save them. However, in practice, they often make huge cuts in staff, raise prices, and do everything they can to pressure higher sales. They can also contribute to consolidation which decreases competition.

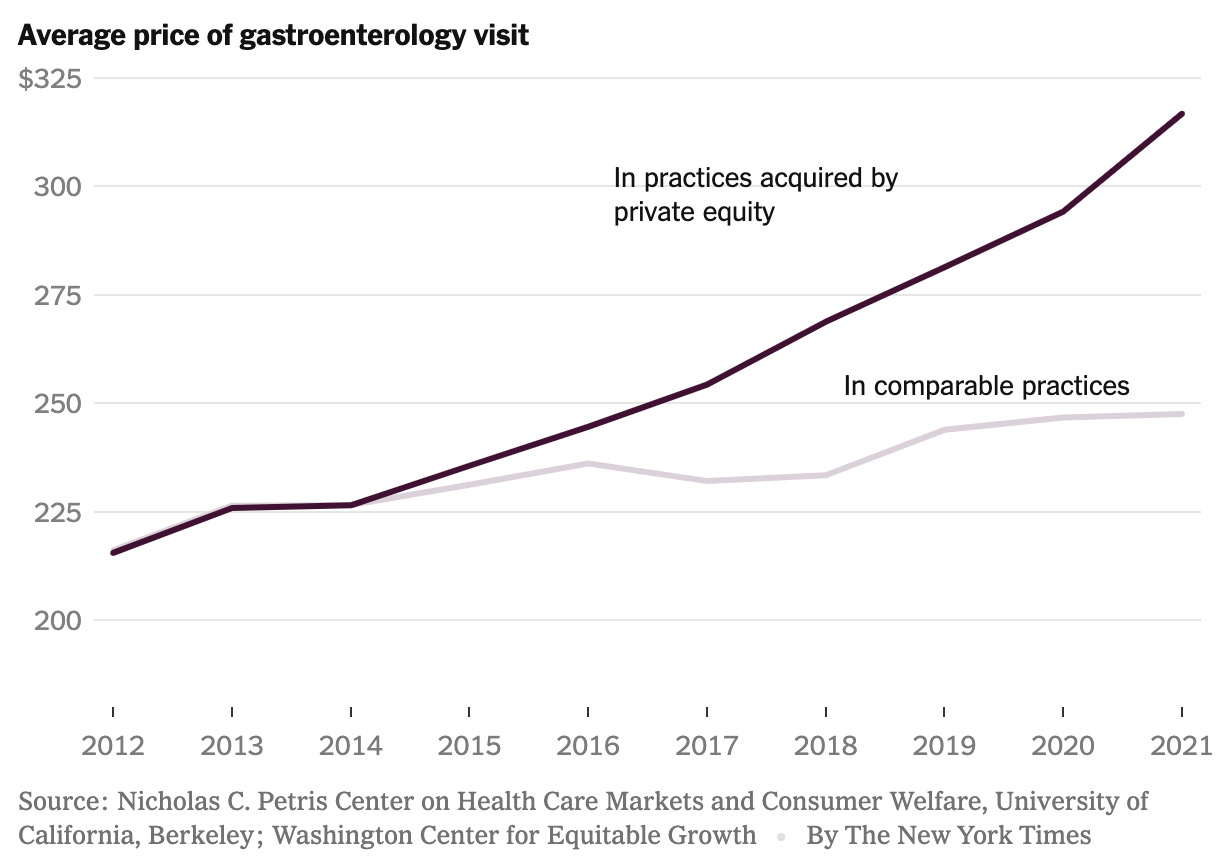

According to the American Antitrust Institute, in more than 25% of markets a single PE group owned a third of specialty medicine practices. Not surprisingly, with this level of consolidation and a drive to get ROI, these practices charge substantially more than their independent and hospital-group peers:

A similar trend is occurring in veterinary medicine:

“Since the start of 2017, private equity dealmaking in the US veterinary sector has totaled over $45 billion, according to PitchBook data. For firms that are active in the industry, clinic acquisitions have mirrored the growth of human healthcare, according to Rebecca Springer, a private equity analyst at PitchBook.

…

One PE firm in particular, Shore Capital Partners, has been a key player in the past few several, rolling up hundreds of veterinary clinics through two of its portfolio companies, Southern Veterinary Partners and Mission Veterinary Partners. Together, they own around 660 clinics nationwide, according to the firm.”

To be clear, I am not saying PE-backed human medical or veterinary clinics are evil (like some histrionic articles I’ve read that I won’t link to). I truly believe their healthcare providers and staff want to help people and animals just like their independent colleagues. What is undeniable is those folks have less freedom to set prices, dictate medical guidelines, and personalize care plans when investors are looking over their shoulders. It is also true that huge, ostensibly “non-profit” human hospital chains (that often behave indistinguishably to for-profit entities) and non-PE corporate consolidators in vetmed contribute to decreasing competition in many markets, although to me a key difference is that regular corporations and non-profit medical groups are usually in it for the long haul and not looking to “flip” their practices after wringing them out like PE does.

Doctors Caught in This System Face Moral Injury

As you can imagine, practicing as a doctor in this modern, complicated, morally ambiguous system is difficult. A 2018 STAT opinion piece by two practicing MDs cast the problem in stark relief:

“In an increasingly business-oriented and profit-driven health care environment, physicians must consider a multitude of factors other than their patients’ best interests when deciding on treatment. Financial considerations — of hospitals, health care systems, insurers, patients, and sometimes of the physician himself or herself — lead to conflicts of interest. Electronic health records, which distract from patient encounters and fragment care but which are extraordinarily effective at tracking productivity and other business metrics, overwhelm busy physicians with tasks unrelated to providing outstanding face-to-face interactions. The constant specter of litigation drives physicians to over-test, over-read, and over-react to results — at times actively harming patients to avoid lawsuits.

Patient satisfaction scores and provider rating and review sites can give patients more information about choosing a physician, a hospital, or a health care system. But they can also silence physicians from providing necessary but unwelcome advice to patients, and can lead to over-treatment to keep some patients satisfied. Business practices may drive providers to refer patients within their own systems, even knowing that doing so will delay care or that their equipment or staffing is sub-optimal.

Navigating an ethical path among such intensely competing drivers is emotionally and morally exhausting. Continually being caught between the Hippocratic oath, a decade of training, and the realities of making a profit from people at their sickest and most vulnerable is an untenable and unreasonable demand. Routinely experiencing the suffering, anguish, and loss of being unable to deliver the care that patients need is deeply painful. These routine, incessant betrayals of patient care and trust are examples of “death by a thousand cuts.” Any one of them, delivered alone, might heal. But repeated on a daily basis, they coalesce into the moral injury of health care”

These painful issues confront veterinarians, too. Both industries face a crisis of burnout and fragile mental health. Unfortunately, there are no free lunches or easy answers. The prescription by the two doctors above is a tall order:

“What we need is leadership willing to acknowledge the human costs and moral injury of multiple competing allegiances. We need leadership that has the courage to confront and minimize those competing demands. Physicians must be treated with respect, autonomy, and the authority to make rational, safe, evidence-based, and financially responsible decisions. Top-down authoritarian mandates on medical practice are degrading and ultimately ineffective.”

The Extreme End of the Spectrum: Dr. Death

For the last part of this article, I wanted to include an extreme outlier in excess care that goes far beyond anything discussed earlier. The Michigan oncologist Dr. Farid Fata provided fraudulent diagnoses and administered chemotherapy to patients who did not need it, and was sentenced to jail after years of perpetuating the scam. This level of intentional, sociopathic malpractice is fortunately very rare. Still, there are lessons for the broader medical industry in this saga. His story, and those of his victims, was told in the harrowing second season of the podcast Dr. Death.

I listened back in 2020 when the whole season was free. They have since required a subscription to Wondery+ to listen to the entire season, but the first episode is still free:

The sixth episode of the season titled “How to Spot a Dr. Death” talks to internist Dr. Danielle Ofri (previously featured on an edition of Weekend Roundup) about what to look for when assessing a healthcare provider to look for red flags about inappropriate treatment.

Great, great reportage. Is this congery of problems just an American phenomena or is it, it something like it, encountered everywhere? Frankly, after reading this, I don't want to deal with any GP or specialist who doesn't practice minimalist/conservative medicine.

I've thought for years that the insurers and economics were the drivers forcing health delivery systems and individual providers to skew their practices. Moral ambiguity from the moment a PT enters the door....