What's the Deal with the Saline "Agglutination" Test?

A deep-dive into this deceptively simple test methodology and what the research says

We’ve all been there—It’s late at night at your ER clinic, you have “Fluffy,” a weak, severely anemic Cocker Spaniel in front of you, and you’re asking yourself: “Could this be IMHA?” In the cobwebs of your memory from vet school you recall that simple bedside diagnostic, the saline agglutination test (SAT). Should you perform a SAT in Fluffy? How do you do actually… do it? What information does it tell you? What do studies say about this test performance? Let’s discuss below!

The SAT is also referred to as the “saline dispersion test” by some, and I prefer this terminology because it highlights the reason you would perform this test: to discriminate autoagglutination of red blood cells (caused by antibodies and/or complement in IMHA) from Rouleaux or other mimics when you see gross or microscopic evidence of RBC clumping. Importantly, if there was no evidence of agglutination to begin with, adding saline to the blood isn’t going to do anything (besides create a mess!)

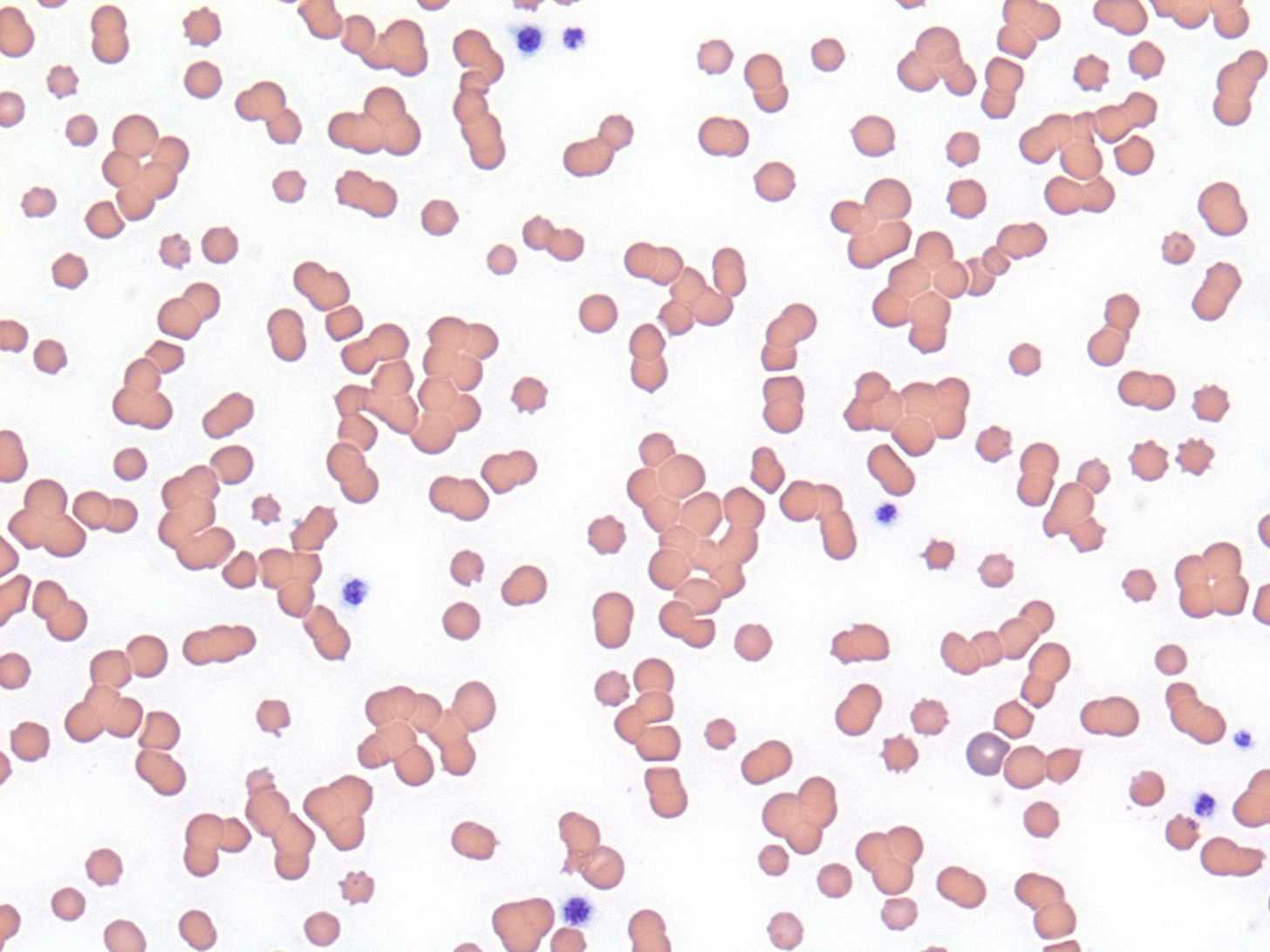

When you look at Fluffy’s lavender-top EDTA tube, you notice slight clumping that might be autoagglutination. Looking at the stained peripheral blood smear under the microscope, this is what you see:

Based on the gross and microscopic suspicion of autoagglutination, performing an SAT is definitely indicated. How do you actually do that? According to the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) consensus statement on the diagnosis of IMHA in dogs and cats, mix blood with saline at a ratio of 1:1 to 1:41 (more on this ratio later…) and evaluate an unstained wet mount preparation. You can do this on a microscope slide, but in my experience, gently mixing these in a red top tube and then using a microcapillary tube or Pasteur pipette to transfer to a microscope slide creates a better mix and reduces any mess. Then, place a coverslip over the droplet of diluted blood, put the slide on the microscope and drop the substage condenser below to increase contrast (similar to performing a urine wet mount or fecal flotation). See below:

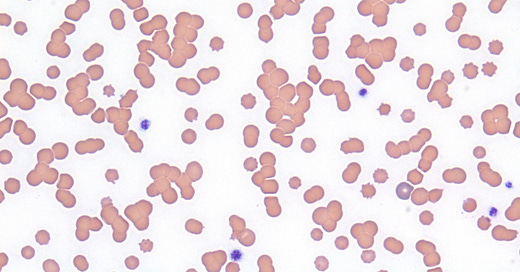

Now that we have the microscope in the right position, let’s evaluate:

Adding the saline has dispersed all of the RBCs clumps, which occurs with Rouleaux (which is caused by mild electrostatic charge effects), but would not happen if they were bound by antibody/complement complexes. Therefore, this is a negative SAT, and argues against IMHA in Fluffy.

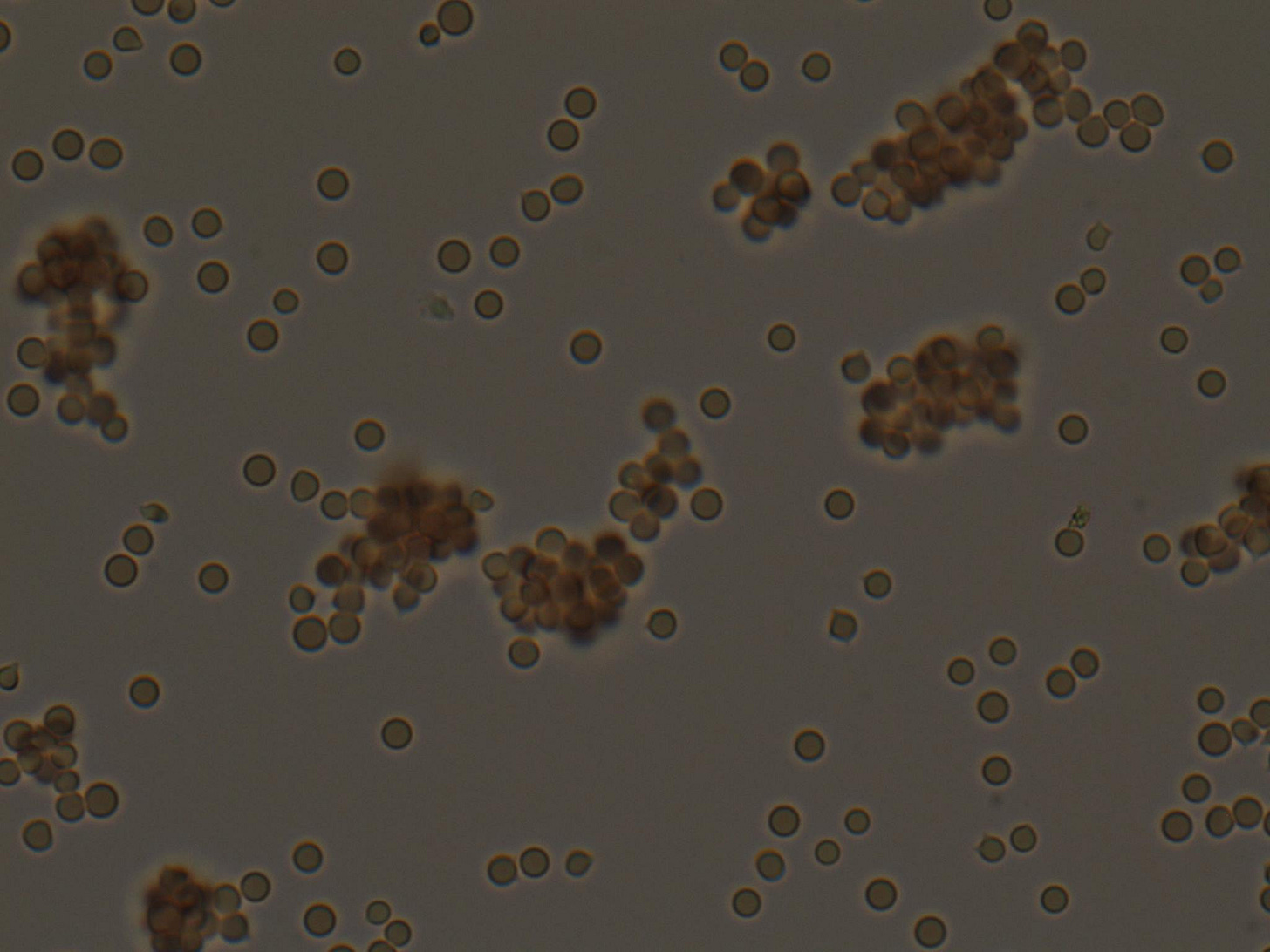

In contrast, a positive SAT (image from a different patient) looks like this:

Now back to the ideal ratio of blood to saline to use for an SAT… A recent prospective study evaluated a wide range of different saline concentrations and how it impacted the diagnostic performance for IMHA2. The researchers compared SATs in a group of 9 dogs with IMHA [based on evidence of hemolysis AND a positive direct antiglobulin test (DAT/Coombs’ test, the gold standard for diagnosis of IMHA3)] versus a group of 138 anemic dogs where there was either no hemolysis, another definitive mechanism for hemolysis identified, or a negative DAT. They replicated the SAT with ratios of blood to saline of 1:1, 1:4, 1:9, and 1:49.

Their results really surprised me when I first read this paper. They found the specificity for a 1:1 ratio was only 29%. Specificity is the ability for a test to correctly identify a patient without the disease, which means almost 70% of the dogs without IMHA in this study would have a false positive result! The good news is the specificity increased with each dilution, up to 97% at the 1:49 dilution. The sensitivity, or ability for a test to catch positive cases, dropped somewhat from 87% at 1:1 ratio to 67% at the 1:49 ratio. The overall diagnostic accuracy for a 1:1 SAT was a poor 33%, but this soared to 95% for SAT at a 1:49 ratio.

Here are my take-home lessons from these studies:

A saline dispersion/agglutination test is performed only when you see gross or microscopic evidence of possible agglutination

You perform a SAT by mixing blood with a sufficient ratio of saline and evaluating a wet mount slide under the microscope

RBC clumps that disperse are a negative result that suggests the patient does not have real agglutination, while clumps that persist confirm agglutination and support a diagnosis of IMHA

The ratio of blood to saline is important, and recent research indicates a large dilution (1:49) had the best accuracy

Diagnosis of IMHA is complex! A DAT/Coombs’ test is considered the gold standard, but it is often not possible to get those results in a time sensitive manner. Other criteria including evidence of hemolysis and identifying spherocytes

Update

I recently came across this letter to the editor of JVIM by Dr. Urs Giger that provides some critiques of the Sun & Jeffrey study, as well as additional thoughts on the diagnosis of IMHA and use of the DAT. I have quoted his key points below:

“Their small number of selected DAT positive cases led to large confidence intervals. In my view, the statistical analyses and sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy of the DAT kit and SAT provided in their small study of a potentially skewed population of DAT positive dogs are premature and likely, as in most other studies of IMHA in dogs faulty due to many misdiagnoses of IMHA in dogs tested. Without a definitive diagnosis of IMHA, claims of false positive and false negative results should be avoided.”

“…While Sun and Jeffery's study refutes the ACVIM consensus recommendation and usefulness of the regular SAT (1 : 1, 1 : 4, and even 1 : 9 dilution) for making a diagnosis of IMHA in dogs, and thereby confirms my prior statements over the past,3, 4, 7 they now recommend a drastically modified SAT (1 : 49, which is more similar to 3x washing in my clinical diagnostic approach) on the basis of their very limited study with few cases of IMHA that excludes many DAT positive anemic dogs.”

“…I encourage everyone to perform a DAT to directly document antibody and/or complement bound to erythrocytes for diagnosis of IMHA rather than relying on any SAT methods; the Coombs' test is also the standard used in human medicine.”

Garden OA, et al. ACVIM consensus statement on the diagnosis of immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in dogs and cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2019 Mar;33(2):313-334. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30806491/

Sun PL, Jeffrey U. Effect of dilution of canine blood samples on the specificity of saline agglutination tests for immune-mediated hemolysis.” J Vet Intern Med. 2020;34:2374-2383. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33169867/

Caviezel LL, Raj K, Giger U. Comparison of 4 direct Coombs' test methods with polyclonal antiglobulins in anemic and nonanemic dogs for in-clinic or laboratory use. J Vet Intern Med. 2014 Mar-Apr;28(2):583-91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24433319/

I'm a bit confused by the addendum - so in practice I typically do 1:4 and sometimes go to 1:10 due to a vethive CE on SAT. I've never gone higher. Although I haven't had MANY IMHA cases that weren't just referred due to how ill they were and need for transfusion. To streamline our work since GP is always very busy, would you recommend to start at 1:10 and maybe do a second at 1:49 if positive at 1:10? I imagine at 1:10 most rouleaux would disperse by then. Or alternatively, if negative for clumping at 1:10, consider a dilution of 1:4 with the notion that some rouleaux may still be present and to definitely base a diagnosis off the Coomb's test? Ty