Is This Test *Really* Necessary?

Exploring the causes and solutions to over-testing in medicine

I’m going to let you in on a secret: A lot of tests in medicine are unnecessary.

Actually, it’s not a secret at all, but a well-known issue in healthcare.

When we say “unnecessary,” this can mean several different things. One possibility would be a test for a condition the patient is extremely unlikely to have, like an exotic infection only found outside the US for a patient with no travel history. Another could be one where the test results won’t change the treatment plan or add clinically useful information (such as prognosis). This could also mean a test that is not validated or can’t provide the information desired.

Over-ordering diagnostics has a number of harmful impacts on patients, ranging from higher medical bills, to stress and anxiety, to complications from sample collection or exposure to radiation (for imaging tests). These negative effects are amplified because tests tend to drive more tests: A weird result on one will require follow-up to figure out what, if anything, it means. And for common tests like routine bloodwork, you should know that the way reference ranges are calculated only covers 95% of normal patients, so the odds of having an “abnormal” result by chance on a panel with a dozen or more parameters is quite high.

The financial aspect is particularly relevant to veterinary medicine, where clients often have limits on the amount of money they’re willing or able to spend on their pets. The so-called “minimum database” recommendation of a complete blood count (CBC), chemistry panel, urinalysis, and imaging of the chest and abdomen can often run in excess of $1,500!

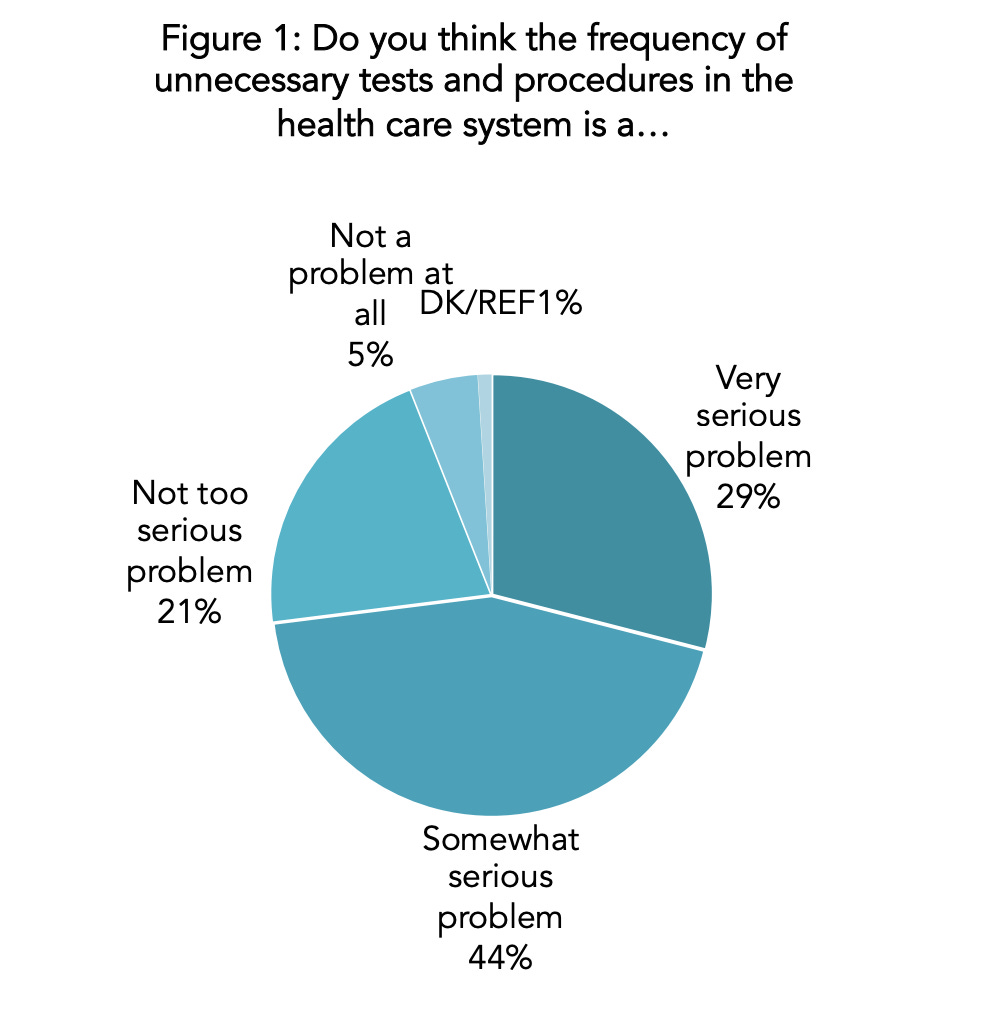

Most physicians (about 75% in one survey) agree that over-testing is a serious concern, the hard part is understanding why it happens, and what to do about it. As someone who has advanced training in laboratory diagnostics and still practices clinical medicine, I think that I am uniquely well-suited to discuss this problem. So today, let’s tackle the issue head-on!

An Epidemic of Low-Value Testing

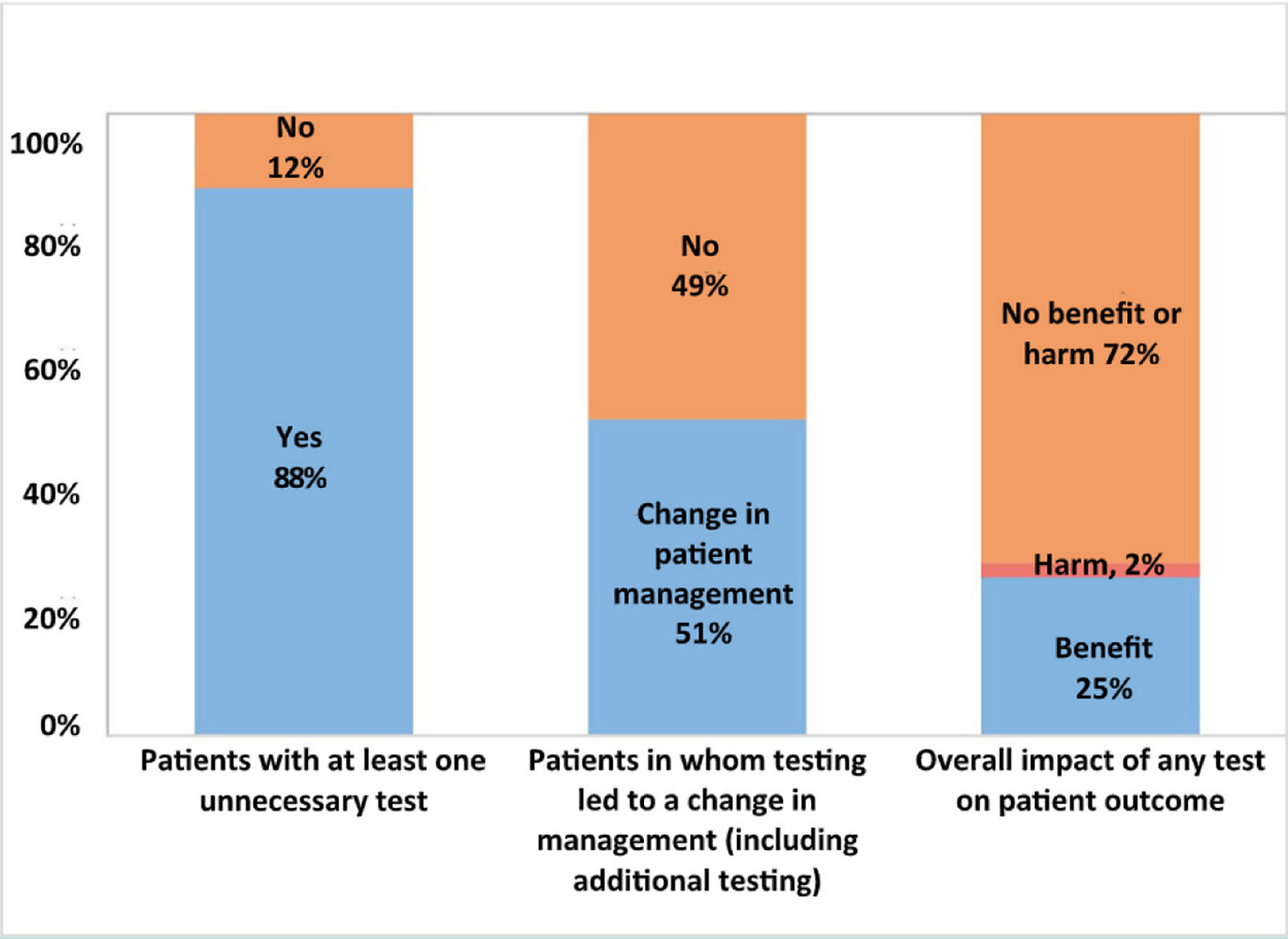

How common are such “low-value” diagnostics? Estimates from individual studies suggest that anywhere between 40 and 60% of tests provide little to no benefit! A 2013 meta-analysis by researchers at Harvard Medical School looking at inappropriate diagnostic test ordering found that almost 1 in 5 tests were unnecessary (“over-utilization”). This rate did not differ much between studies in the US or other countries, nor did it vary by test type (hematology, chemistry, microbiology, etc).

To be fair, this meta-analysis also looked at under-utilization of diagnostics, meaning tests that should have been ordered but were not. Their results actually suggested under-utilization was more common than over-utilization (44.8% vs 20.6%). The authors of the study summed up this seeming contradiction in a blog post:

“It’s not ordering more tests or fewer tests that we should be aiming for, it’s ordering the right tests, however few or many that is”

While I could not find specific studies looking at over-testing or overdiagnosis in veterinary medicine, the prevalence is likely at least as high as in human healthcare.

Examples of “Bad” Diagnostics

What are some examples of tests that “should not” be run? This is a tough question because there are a truly staggering number of possible options a healthcare provider could order, and a test that would be appropriate for one patient might be a waste of time or money for another. Quest and Labcorp offer thousands of specific assays, and the catalog for veterinary diagnostic companies like Antech and IDEXX list hundreds of test codes that can be ordered separately or in combinations.

In 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) launched the “Choosing Wisely” campaign to highlight examples of low-value diagnostics, drugs, and procedures that were not routinely recommended. In the 11 years after, the initiative expanded to more than 21 countries and published over 600 recommendations. While the formal Choosing Wisely campaign ended in 2023, a number of professional societies continue to update those guidelines. Some of the recommendations include1:

Patients who faint but don’t show any other neurologic signs don’t need a CT/MRI

Don’t order a frozen section biopsy (STAT) unless it will impact immediate care

Pre-op chest X-rays don’t add value for routine procedures in healthy patients

Start with a TSH to screen for thyroid disease (rather than full panel of T3, T4, etc)

Base plasma transfusion needs on a patient’s bleeding status, not clotting times

For the veterinary side, there are a few groups that put out best practice documents, like the AAHA guidelines and ACVIM consensus statements. However, these are usually broad in scope and based more on expert opinion than published evidence (because it is often lacking). I’m not aware of any organization in our field that has specifically investigated effective utilization of diagnostics.

When I think about diagnostics in veterinary medicine that are low-value, here are a few that jump out:

Cytology of mammary masses in dogs

Cannot accurately differentiate benign from malignant tumors

Regular X-rays of the skull for sinus/nasal pathology

Poor detail compared to CT, rhinoscopy, and other modalities

Anti-platelet antibody testing for immune-mediated thrombocytopenia

High rate of false positives and negatives

Does not change management or improve outcomes

Many FIP diagnostics

Most cats have been exposed to feline coronavirus, so serology has poor sensitivity and specificity

PCR for feline coronavirus can be useful when run on body cavity effusions, but it is not accurate when run on blood or previously-stained cytology slides

AI diagnostics in radiology and pathology

These often have little to no published data to show that they work

“Black box” nature means it can be impossible to troubleshoot weird results

Novel “cancer screening tests”

Often not validated

Many can’t tell you where or what cancer might be present, so they often trigger a frustrating fishing expedition work-up

Reasons for Inappropriate Ordering

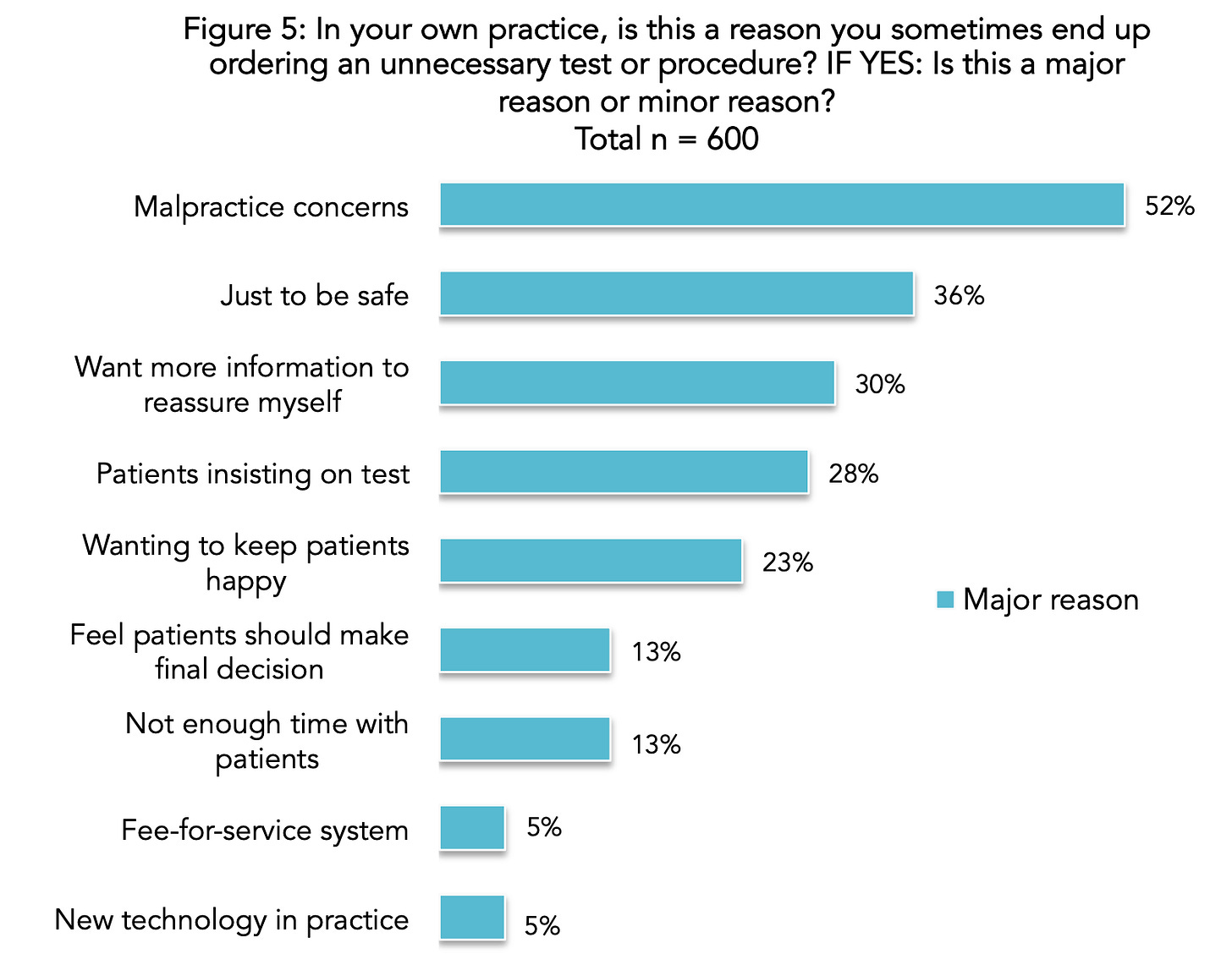

I don’t think most clinicians consciously think to themselves “I am going to order a pointless test.” Rather, there are a lot of subtle reasons that lead physicians and veterinarians to err on the side of ordering a test vs a more conservative approach.

Defensive Medicine

As the ABIM survey graphic above shows, a major driver of test ordering in human medicine, and likely veterinary medicine as well, is fear over legal liability. In fact, just yesterday the New York Times published a story on “the worst test in medicine” (continuous fetal monitoring), with lawsuits being one of the main factors:

“Obstetricians are more likely to get sued than doctors in any other medical specialty. Monitoring records often become critical evidence, with expert witnesses on each side offering competing interpretations.

In July, Ms. Gunn represented a Missouri family who won $48 million — the state’s largest malpractice verdict in decades — after using monitoring records to claim that a hospital was responsible for a baby’s cerebral palsy. In a similar case that month, a Pennsylvania court ordered a hospital to pay $207 million. A Utah judge went even higher in August, awarding $950 million to the family of a brain-injured baby.”

It’s not hard to see how the threat of an eight or nine figure malpractice settlement, to say nothing of insurance premiums or damage to career, leads to an excessively cautious approach! In that same 2014 ABIM survey of physicians, 91% said that medical malpractice reform would significantly reduce such “defensive medicine.”

I’d also argue that fear of judgment from colleagues is a closely related phenomenon. The conditioning starts early, with med students seeing their faculty members questioning, or even chastising, the case management of referring clinicians. Nobody wants to look like an incompetent doctor that missed an obvious diagnosis, so running an extra test or two to CYA can seem like a small price to pay.

Diagnostic Uncertainty

In a perfect world, every disease would be black and white, and doctors would have 100% certainty in their diagnosis and treatment plan. Unfortunately, in the real world this is often not the case. Patients can have atypical presentations of common diseases, where they lack many of the key signs and symptoms. They can also have multiple concurrent pre-existing conditions, and be on several medications, which muddies the waters.

A practitioner might be correct about a patient’s diagnosis, but lack confidence and defer to more testing to reassure themselves. I would argue that my doctors performed a lot of unnecessary infectious disease tests when I was hospitalized last summer because they were not confident it was simply a case of community-acquired pneumonia (it was).

Research has shown that younger doctors are less tolerant of diagnostic uncertainty than older colleagues, as noted in this study from the Journal of Veterinary Medical Education:

“Results suggest pathology professionals become more tolerant of ambiguity (TOA) throughout their careers, independent of increasing TOA with age, and that navigating ambiguity might be more difficult for trainees than for professionals. Educational interventions might help trainees learn to successfully navigate ambiguity, which could impact psychological well-being.”

Helping younger colleagues navigate these “gray areas” of medicine may reduce unnecessary testing.

Not Understanding How the Test Works

In some cases, a misunderstanding about how an assay actually works can lead to ordering something inappropriate, or even a misdiagnosis. There are plenty of examples:

— Running a saline agglutination test incorrectly or when it isn’t called for → False positive IMHA diagnosis (My first All Science article was on this issue!)

— FIP PCR run on previously-stained cytology slides → Feline coronavirus is an RNA virus, so the cellular material on a slide that has been sprayed with a bunch of chemicals and stains will be exposed to RNAses and other compounds that degrade the viral genome (false negative)

— Running a test for a rare pathogen (I.e. Leishmania in a US dog with no travel history) → When the prevalence of a disease is very low, most positive results are likely false positives

— Submitting flow cytometry or PARR on blood with very rare atypical cells → any possible positive signal will be buried in background noise (false negative)

Excitement About New Technology

Doctors are scientists at heart, and many of us are eager to try out new devices and procedures because we’re largely a pro-technology group. However, just because there is a splashy new test on the market doesn’t mean it is better than the existing standard!

Right now, artificial intelligence is all the rage and there has been an explosion in “AI-powered” lab and radiology tests. Last summer I wrote a piece about the many problems with a new machine learning thermography device that claims to be able to “rule out cancer” without a biopsy:

Likewise, another trendy topic has been screening blood tests that claim to detect cancer earlier. Many of these have low sensitivity and/or specificity, and none to my knowledge have demonstrated that earlier diagnosis improves survival times to justify their expense.

Financial Incentives

Finally, we have to talk about the elephant in the room: $$$

While I don’t think money is the major motivation for ordering tests—and physicians surveyed reported it as one of their lowest considerations—it is undeniable that diagnostics make up a substantial portion of hospital revenue.

In veterinary medicine, many DVMs are paid on a percentage of their production, so ordering more tests means a higher salary. Most vets I know are in it for the love of animals, and a lot are frankly terrible at business, frequently discounting their own services. The most plausible impact of financial considerations seems to be in marginal or gray area situations where you can think of arguments for and against running a particular diagnostic, and it serves as a tie-breaker, of sorts.

Solutions

At this point, hopefully I’ve convinced you that excessive testing is a problem, and discussed some common reasons why it happens. What do we do about it? I think there are three groups of stakeholders that can make a difference: medical organizations, individual clinicians, and patients (or pet owners).

Institutions

Efforts like “Choosing Wisely” and the ASCP guidelines for responsible testing are a great start! We desperately need similar efforts in veterinary medicine, and organizations like the AVMA, AAHA, and ACVIM should lead the way.

One of the big limitations is a lack of research in this area. I would argue that veterinary academia should prioritize conducting comparative effectiveness research on existing tests at least as much as developing new tests, especially since the private sector has less incentive to publish any information that reduces the market for their own products, and there is no equivalent to the FDA or CMS-CLIA.

Veterinary schools should also strive to set a better example for students and not denigrate the choices of their colleagues; they were not in the room with the owner or pet, so they don’t know all of their considerations. CVMs could also start introducing the concept of “spectrum of care” and formulating flexible care plans.

Clinicians

Individual physicians and veterinarians are the ones who actually order these tests, so we are in a key position to address the problem. We should constantly be asking ourselves:

Will this test change what I do, or am I just curious or seeking reassurance?

What is the evidence this will improve length or quality of life for my patient?

Am I submitting the right type of test on the right sample to answer my question?

Has this test been rigorously validated by an independent organization?

Patients

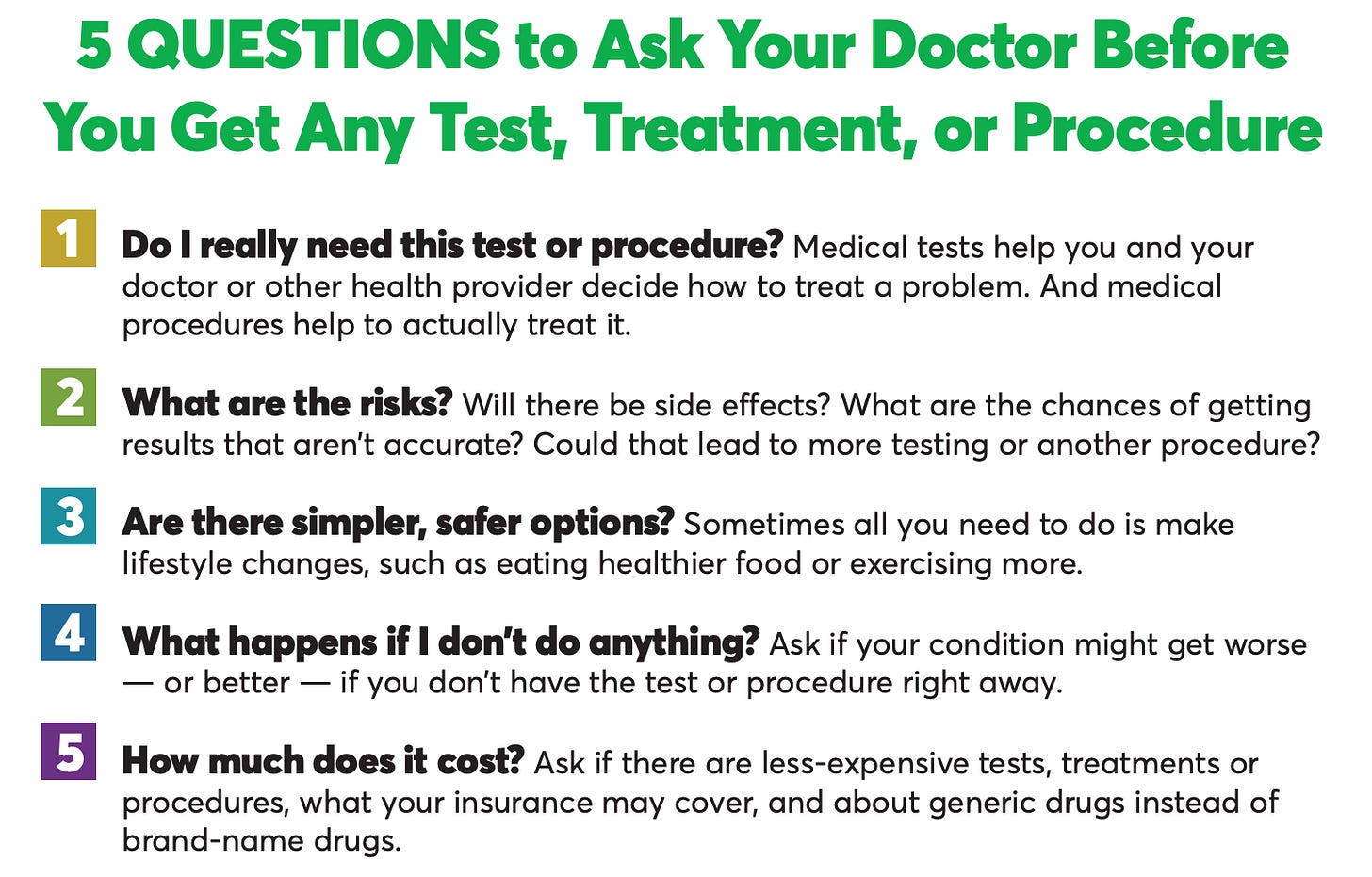

At the end of the day, patients (and pet owners) have the ultimate control because they can give or withhold consent for any care plan. I would recommend asking tough questions of your doctor, and the list below from the Choosing Wisely campaign provides some helpful prompts. If they don’t feel something is necessary, you can always consider a second opinion, but I would caution against serial “doctor shopping” to get what you want; note that in the ABIM survey, a common reason for ordering a low-value test was to placate an insistent patient!

Inappropriate testing is a serious issue, but together we can make better choices. If you have any comments or questions, leave a message below!

—Eric

Sources:

American Society of Clinical Pathology (ASCP): “Effective Test Utilization Recommendations”

CBC/CHEM/T4/UA and 3 views of chest with exam...less than $500 at my practice. Which I agree is a lot. I don't do tests that won't change my treatment plan.

Interesting read! Working in veterinary ER, I resonate with the fear of a liability risk. I’ve also been bitten in the a** a time or two for choosing imaging over bloodwork or vise versa when a pet owner asks me to choose which one I recommend most because they don’t have the budget for both.

I just removed two blankets from a dog’s stomach and intestines at the ER because when they visited their primary vet a few days before, they could only afford bloodwork and not X-rays at the time.

So if I see a dog with anorexia, vomiting, and not eating — they’ll often get an estimate for bloodwork, X-rays, fecal, and pancreatitis test. Now that’s obviously a lot. I offer to go stepwise, but that has pros and cons for animals too. Pet that needs sedation? It’s tough to do one test at a time. Cat that was almost impossible to get in a carrier and get to the vet? The owners usually very much don’t want to have a second vet visit. Owner doesn’t want to spend 4 hours at the vet either.

Anyway, I agree that a recommendation guide would be helpful like in human med.

Tricky topic! Thanks for sharing more on it. I love learning from human med too.