The Bicameral Mind

On returning to the front lines of medicine

Do I contradict myself?

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

— Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself, 51”

Practice and Praxis

Some days this summer made me stop and think, “Wait, who am I today?”

In late June, as I was reading out a bone marrow biopsy on the fourth floor of the University of Pennsylvania veterinary teaching hospital, I was an academic pathologist.

The following week of July 4th, I became a student again, auditing the BluePearl EmERge bootcamp in Minneapolis. I scribbled notes as we blitzed through everything from anesthetic protocols to seizure management, point-of-care ultrasound, and surgical procedures, not wanting to miss any detail.

Immediately after that I took on the role of teacher, lecturing the second year class at Ross University in the Caribbean about acid base and electrolyte disorders.

When I got back to the US, I was a practicing veterinarian again, vaccinating kittens at PetCo and flushing out dog bite wounds in the ER.

Other days, I’m a writer, a conference speaker, a lab business consultant, or a scientist peer-reviewing research manuscripts.

It’s enough to induce vertigo.

***

When I don my scrubs and stethoscope, part of me feels like I am merely cosplaying as a vet. While I did an internship and moonlighted in the ER throughout my residency, it’s been years since I quit working on the clinic floor. Imposter syndrome stalks me on every shift. I worry that I’m one stupid question or bad call away from being “found out” as a fraud who shouldn’t be there.

I’m still brushing up on many things I forgot years ago. Almost every shift, something pops up that I blank on and need to steal away for a peek in Cote’s Clinical Vet Advisor or the 5 Minute Consult. Every drug calculation gets cross-checked repeatedly. Specialist friends are very patient responding to “drive-by” consult texts.

However, once in a while a magical alchemy happens: some piece of knowledge or experience from one domain spills over into another in a beneficial way. Like the recent case of an older Boxer who presented for weight loss and a fever of 104.5F. All of her lymph nodes were firm and enlarged. My first, second, and third differential was the blood cancer lymphoma. I collected a fine needle aspirate sample and reviewed the slides under the microscope in house, confirming my suspicion. Many vets would have started with a shotgun diagnostic approach before cytology—full labwork and imaging—which would not be wrong, but could cost upwards of $1,000 and would not have given them an answer.

Then there are patients that illustrate the peril of tunnel vision. One night an owner called in to say their Chihuahua with a history of dozens of extracted bad teeth had bleeding around the gums again. To their great credit, the technician who took the call explained that while we didn’t have dental X-ray capabilities, it would be smart for them to come in anyway because it could be something else.

On exam, in addition to minor oral bleeding, I noticed subtle pinpoint hemorrhages (petechiae) on the gums and a small amount of blood in one nostril. Upon further questioning, the owner mentioned their dog’s stools had recently been tarry—a tell-tale sign of GI bleeding. Hmmm… My “spidey sense” was tingling that a severely low platelet count was to blame. A Complete Blood Count (CBC) and blood smear review confirmed the diagnosis was Immune-Mediated Thrombocytopenia (IMT/ITP).

The Sum of the Parts

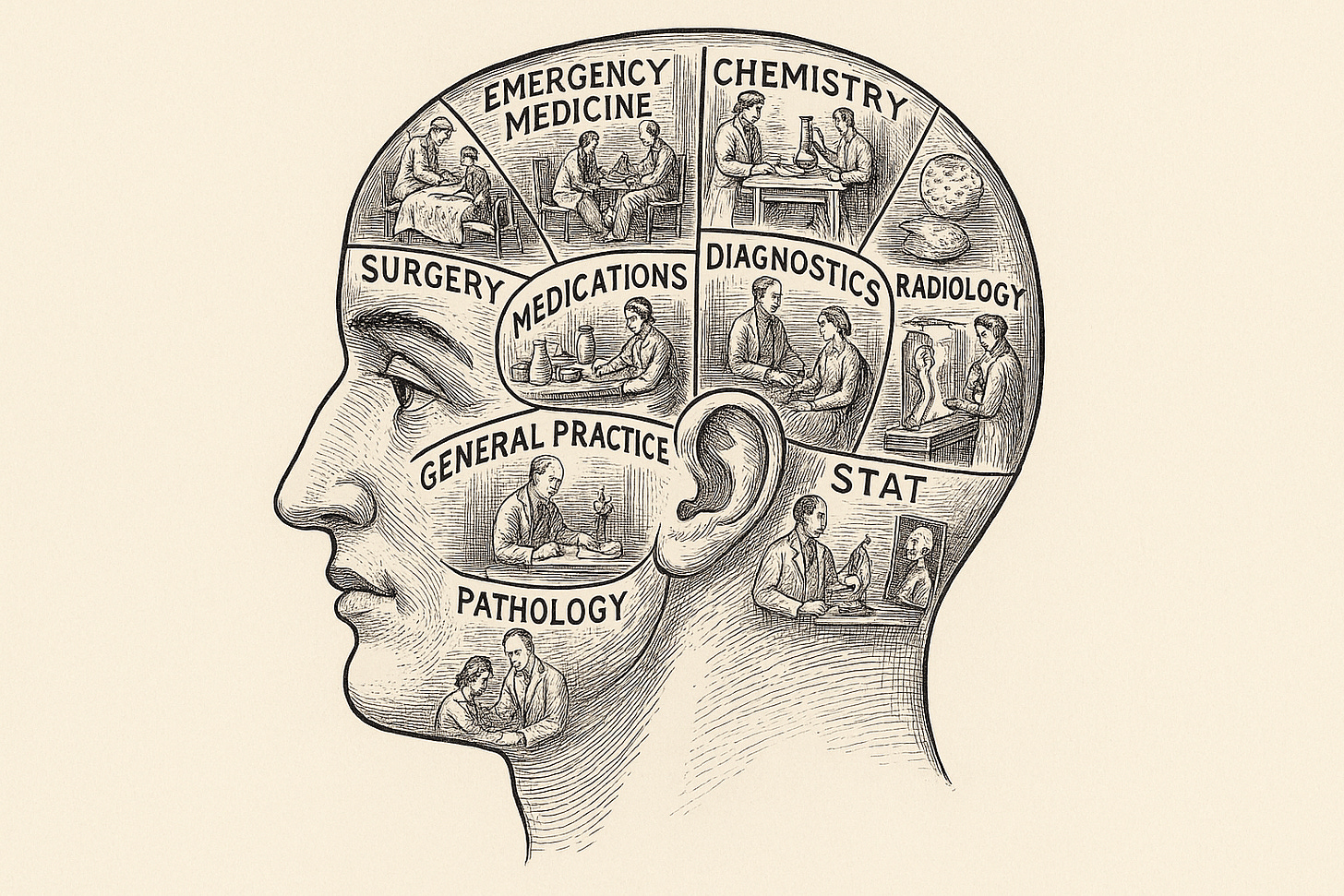

When people ask me what it’s like to constantly switch gears like this, I struggle to come up with the best metaphor. One obvious candidate would be “code switching,” where one changes their outward behavior, dialect, and even appearance to blend into different environments. To be sure, when I’m working as an emergency vet, I put on the appropriate “costume” and have to translate my medical jargon into layman’s terms. Where code switching fails as a metaphor is that it is primarily an outward or superficial change for fitting in, rather than a deep shift in how you think.

Another analogy could be a computer loaded with two different operating systems, like Windows and MacOS or Linux. However, this goes too far in the other direction, as the hard-drive would be partitioned such that there is no data transfer or influence between two separate sections that are digitally walled off from each other1.

The metaphor that I like the most is Julian Jaynes’s concept of the “bicameral mind,” which inspired the plot and subtext of the HBO sci-fi drama Westworld. Essentially, Jaynes proposed that primitive humans did not possess conscious introspection the way modern people do. Rather, they experienced the thoughts arising from one part of their brain as instructions from the gods or other supernatural phenomena.

Where the bicameral mind theory gets really interesting is what happened next: Jaynes proposed that a crisis in civilization around 2,000 BCE led to the collapse of bicamerality and literally changed our brains to develop holistic consciousness as we would understand it today. In Westworld, the humanoid robots of the park find themselves torn between the voices in their head (instructions from their programmers) and their day-to-day lived experience, which often conflict. This cognitive dissonance causes them to become sentient and independent.

Many biologists and neuroscientists have criticized this theory as inaccurate, although on a simplistic level, the concept is not so different from the more widely accepted framework of System 1 / System 2 thinking described by Daniel Kahneman in his famous book Thinking, Fast and Slow. Furthermore, we’ve long known that the two halves of the brain (or hemispheres) have different compartmentalized functions. When the tissue that connects them called the corpus callosum is severed, patients can experience deficits in perception and motor function, including an out of body sensation, although the brain is highly plastic and can “rewire” itself over time.

***

My dual life as a practicing clinician and pathologist was similarly triggered by a career crisis of my own. While I would not have voluntarily chosen this sequence of events, it has some benefits. On a day to day basis, I must draw on very different knowledge bases, languages, and skill sets from different phases of my career. I can feel long-dormant neural circuits reawakening in me.

Once again laying hands on animals puts me in touch with a more immediate, humanistic side of medicine. The famous veterinary internist Dr. Steve Ettinger once said “Nobody cares how much you know until they know how much you care,” and that line stuck with me. Most pet owners are more interested in someone who listens empathetically than one who demonstrates technical wizardry.

Working on the clinic floor has unquestionably made me a better pathologist. I’m more attuned to subtle nuances in the biopsy submission history, and feel comfortable evaluating the radiology images attached the cases. Being the one who has to euthanize patients reminds me of the somber weight of my pathology diagnoses, especially when it is something like terminal cancer.

One thing diagnostic consultants often forget is the financial aspect of medicine. For example, it is easy to be cavalier and insist that every lymphoma case “should” get flow cytometry (typical cost $300-500) to guide multi-agent CHOP chemotherapy. In the real world, I must often formulate a care plan for people who had to apply for credit to cover the exam fee.

When I deliver continuing education lectures at conferences, I can honestly tell the audience that I know what it’s like to be in their shoes, to juggle balance best practice recommendations like “always review your blood smears!” with those hectic shifts where you have three impatient clients in the waiting room while you’re trying to catheterize a blocked cat under anesthesia.

The benefits flow the other way, too. I’m more comfortable parsing labwork now than I was right out of vet school. My residency training helps me dodge common pitfalls, like misdiagnosing pancreatitis based on a positive SNAP test2 or calling IMHA on the thrombocytopenic dog I mentioned above3.

The modernist poet Wallace Stevens once wrote: “In the sum of the parts, there are only the parts / The world must be measured by eye.” Those two lines beautifully sum up the tension between a reductionist worldview and the notion that some truths can only be revealed through subjective experience. Medicine is full of ambiguity, contradiction, and nuance. Like the characters in Westworld, I am learning to integrate and rewire the multitudes of myself, moving from a rigid bicameral mindset to a more complete veterinarian. And that is truly a gift.

—Eric

I will set aside “virtual machines” or instancing, which blurs the line as this can allow simultaneous operation of different operating systems, rather than having to pick between one or the other at a time like a specific boot partition

There are several conditions that will result in false positives, and the best use of that test is to rule OUT pancreatitis with a NEGATIVE

Some staff thought the dog’s blood was autoagglutinating, but I showed the proper way to perform a saline dispersion test (which way negative), and explained that the microcytosis was likely evidence of iron deficiency from bleeding, rather than from spherocytes

Hi Dr. Fish! I’m a GP veterinarian in Kentucky, and I loved this perspective on our lived experience in clinical practice, especially through the eyes of a a specialist!

I’m new to your page (and Substack in general) but I’m excited to keep reading!

Thank you for the link to that article! It looks good.